The Power of Richard Linklater’s Nostalgia

The famed director’s forthcoming Apollo 10 1/2, a movie about growing up in 1960s Houston, takes him places he’s never been before

By Michael J. Mooney

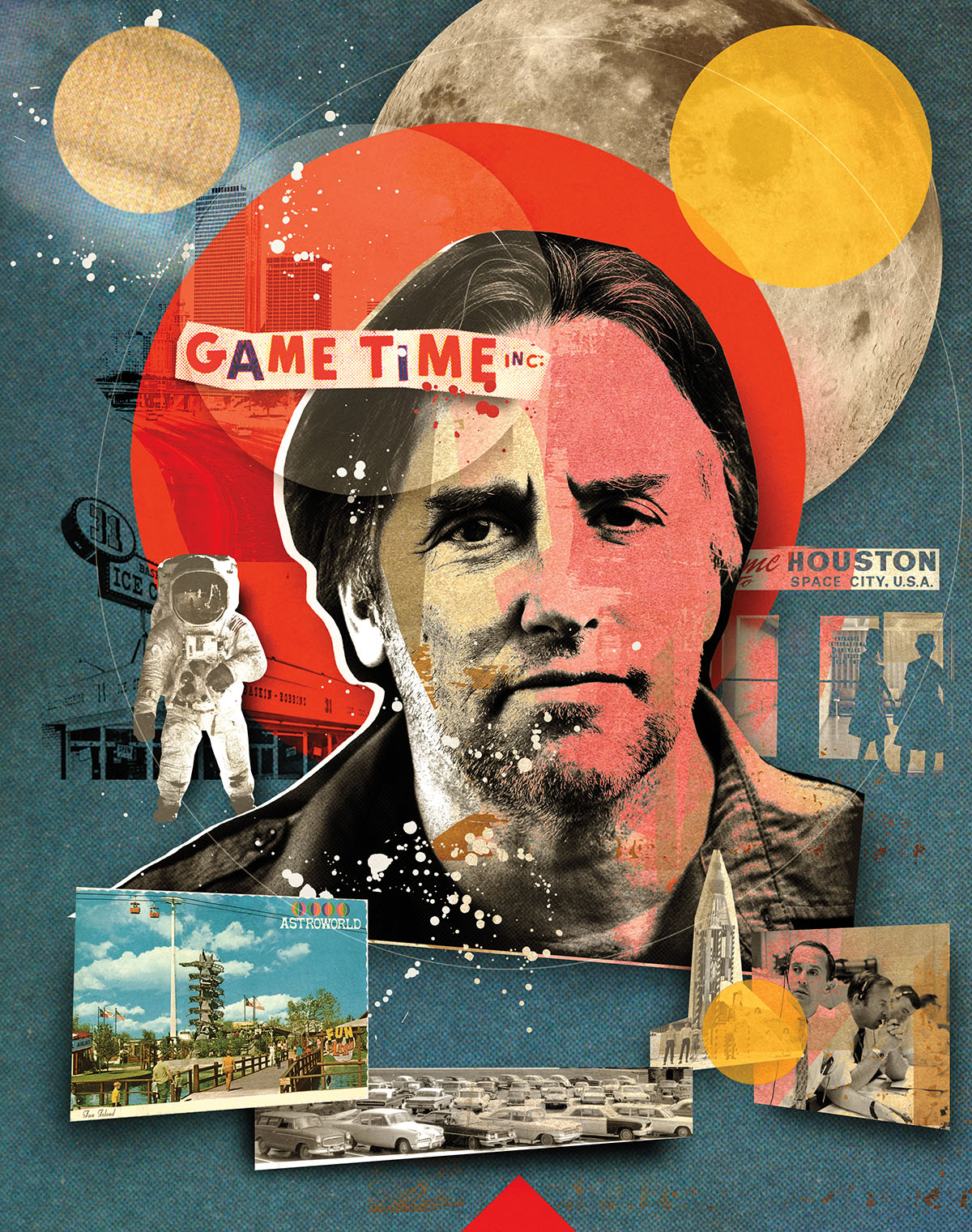

Illustration by Peter Horvath

O

OOn one side of the warehouse-size room, a two-and-a-half story green wall towers over the soundstage. Attached to that wall is another shorter wall, also painted the distinctive green-screen green. A large swath of the floor in front of the walls is the same color, creating a seamless field of infinite green so pristine that most of the crew wears soft blue booties over their shoes to avoid scuffing it.

There are at least 40 people in the room this morning, each responsible for and focused on something different, all weaving and buzzing around a line of cameras, monitors, cranes, and various bright white lights. At the center of it all, wearing a loose gray button-down shirt with the sleeves rolled up, a relaxed pair of Levis, and black Nikes with red laces, is the director: Richard Linklater. Once the actors are in place, the clapboard snaps, and the room gets quiet. Linklater nods.

“All right,” he says in a firm yet calm voice. “Action.”

It’s late February, on the ground floor of Troublemaker Studios in East Austin. But for the purposes of the movie being made, the space is supposed to be the suburban sprawl of Houston in 1969. In the middle of the green soundstage sits an immaculate classic white Chrysler sedan, a whale of a vehicle with an old Texas license plate. It’s parked next to a stand-alone drive-in movie speaker. In the front seat of the car, a couple in their late teens is dressed head to toe in attire taken directly from photos from the 1960s: his orange-striped shirt and slicked-down hair, her light-cotton dress and dangling ponytail. In the scene being filmed, the couple makes out, while two preadolescent boys pretend to sneak up and spy on them.

After a few seconds, Linklater stops the boys, walks in front of the cameras, and points at various markers on the green floor.

“You walked through a car,” the director says matter-of-factly. His calm, urban-Texas drawl makes some of his instruction sound a little like spiritual guidance.

“Remember to stay in your lane,” Linklater tells the boys.

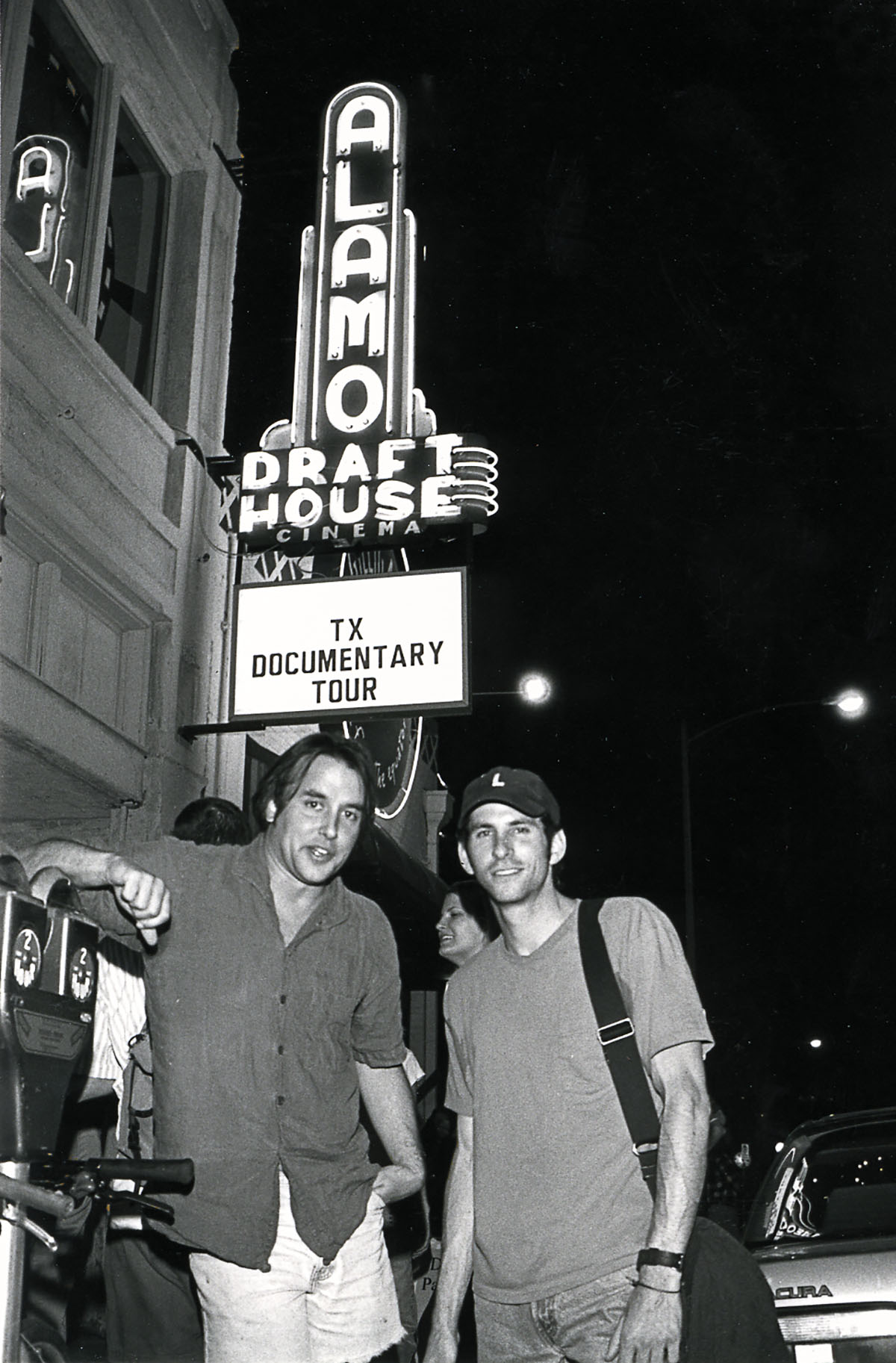

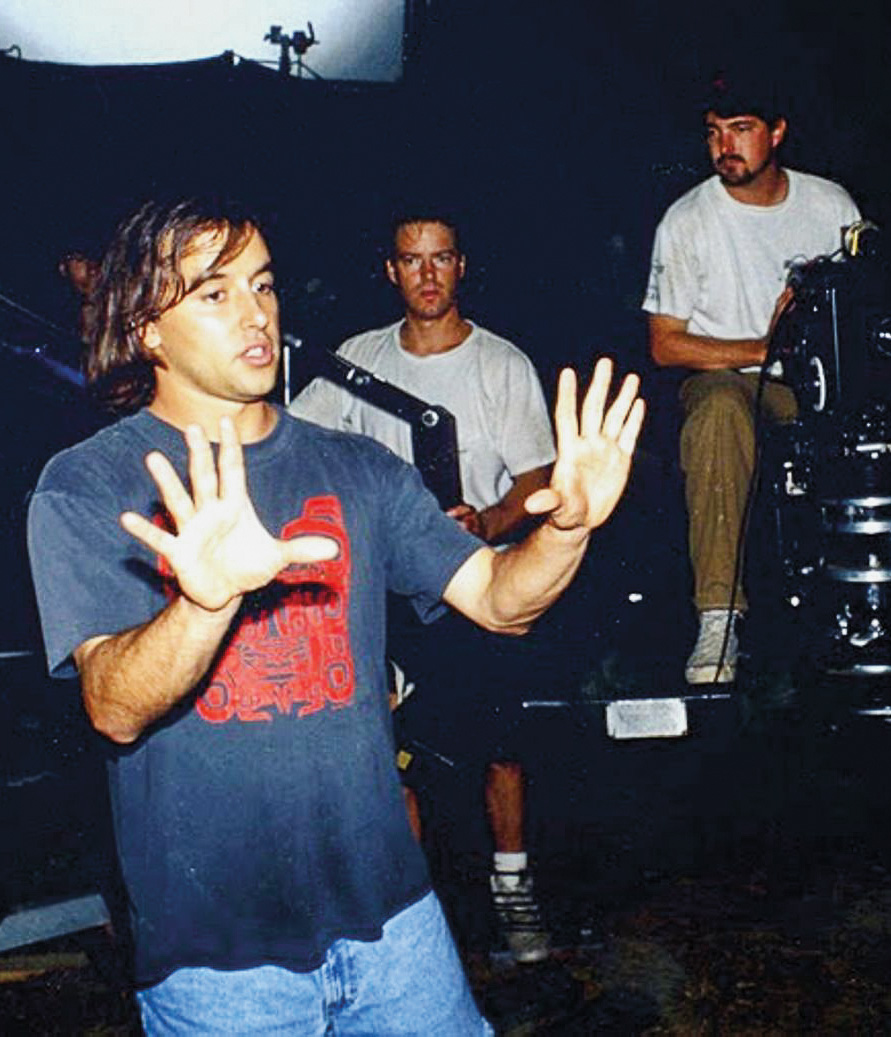

Richard Linklater with S.R. Bindler, director of Hands on a Hardbody, outside the Alamo Drafthouse in Austin circa 1998. Photo courtesy Austin Film Society.

The boys go back to their original marks and walk toward the Chrysler again, this time careful to maneuver around the designated imaginary cars in the imaginary drive-in movie theater. The boys point and giggle at the kissing couple in the car. The director lets the cameras run, encouraging the actors to do whatever feels natural to them in the moment, which is his general approach to directing. There’s more giggling.

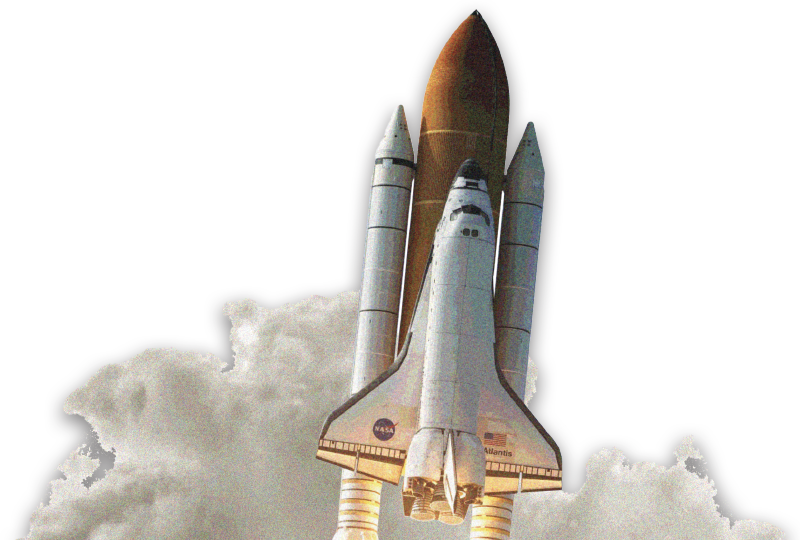

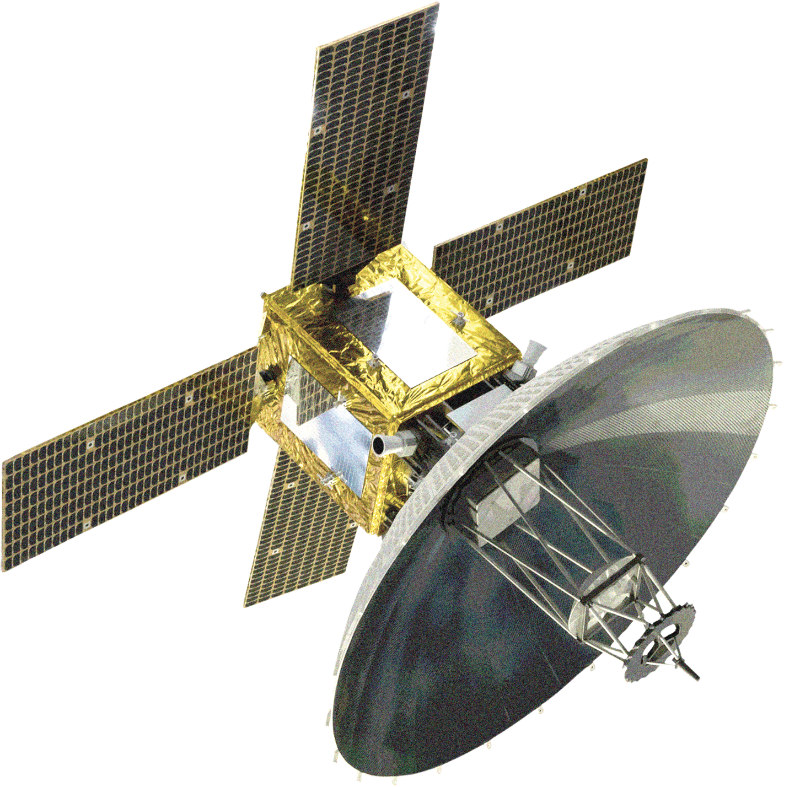

The movie being filmed, slated for release on Netflix in 2021, is called Apollo 10 1/2: A Space Adventure. It will be Linklater’s 22nd feature film, and like much of his previous work, he wrote it himself, and it’s largely autobiographical. The movie is a novelistic look at the life of a 10-year-old boy growing up in Houston in the late 1960s, just as NASA was sending humans to the moon. But unlike any of Linklater’s other films, the entire movie was shot on green screen. The actors will all be Rotoscoped, a dreamlike computer-animation style Linklater employed in his movies Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly. The backgrounds and settings—the drive-in movie theater in the scene with the Chrysler, for example—will be filled in with 3D computer illustrations using decades-old photos and home movies as reference. These images were compiled by the production staff, and some were even submitted by the public.

But beneath all of that—the huge crew and the technical challenges—is a director guiding actors on camera.

“Let’s do it again,” Linklater says. He’s so relaxed, it’s almost like he’s suggesting a restaurant for dinner.

This time, Linklater gives the boys another direction, as they creep toward the kissing teenagers in the car, to bring them into a certain moment and place in history: “You’re happy to be here, too!”

The idea for Apollo 10 1/2 came while Linklater was making Boyhood. That movie, shot over 12 years and eventually nominated for five Golden Globes and six Academy Awards in 2015, followed a boy and his family as they changed and developed over more than a decade. Every year, Linklater would write a short vignette based on a year of the boy’s life. As he prepared to write the third vignette, the filmmaker thought back to what was happening in his own life at that age.

Growing up in Houston during those years felt like living in a real-life science fiction movie, Linklater tells me. Between 1965 and 1969, doctors there performed the nation’s first successful heart transplant; architects built the world’s first domed stadium, replete with newfangled artificial grass dubbed “AstroTurf;” and scientists at NASA were sending men to the moon.

“It was just unbelievable,” he says. “Houston felt like the center of everything scientific.”

Astronauts stepping foot on the surface of the moon united humanity in a way that hasn’t really happened since, he says. Looking back now, it seems more like a fleeting final moment of something now lost to us all.

“This is the last thing that the whole world thought was good,” Linklater tells me.

It’s a few weeks after shooting wrapped on the movie, and he’s talking to me in the library he built on his 48-acre ranch in Bastrop. In relative isolation 30 miles from Austin, Linklater can work on the postproduction of Apollo 10 1/2, as well as a few other projects. Outside his window, birds and crickets chirp and click beneath the afternoon sun. Today he’s working on music cues for the movie. Linklater’s films are known to have incredible soundtracks, and while he can’t name the songs he’s using yet, he assures me they’re all era-appropriate.

As he talks about the movie, his voice grows more enthusiastic and wistful. Since wrapping the shoot, a pandemic has spread around the globe and protests have filled the streets. Linklater says he knows the late ’60s weren’t peace and love for everyone, but watching the Apollo 11 mission as a boy filled him with unbounded optimism. So, he’s enjoyed the opportunity to escape into a different time.

“Fifty years ago,” he says, his voice stretching out the thought. “That’s a good place to be residing during this time.”

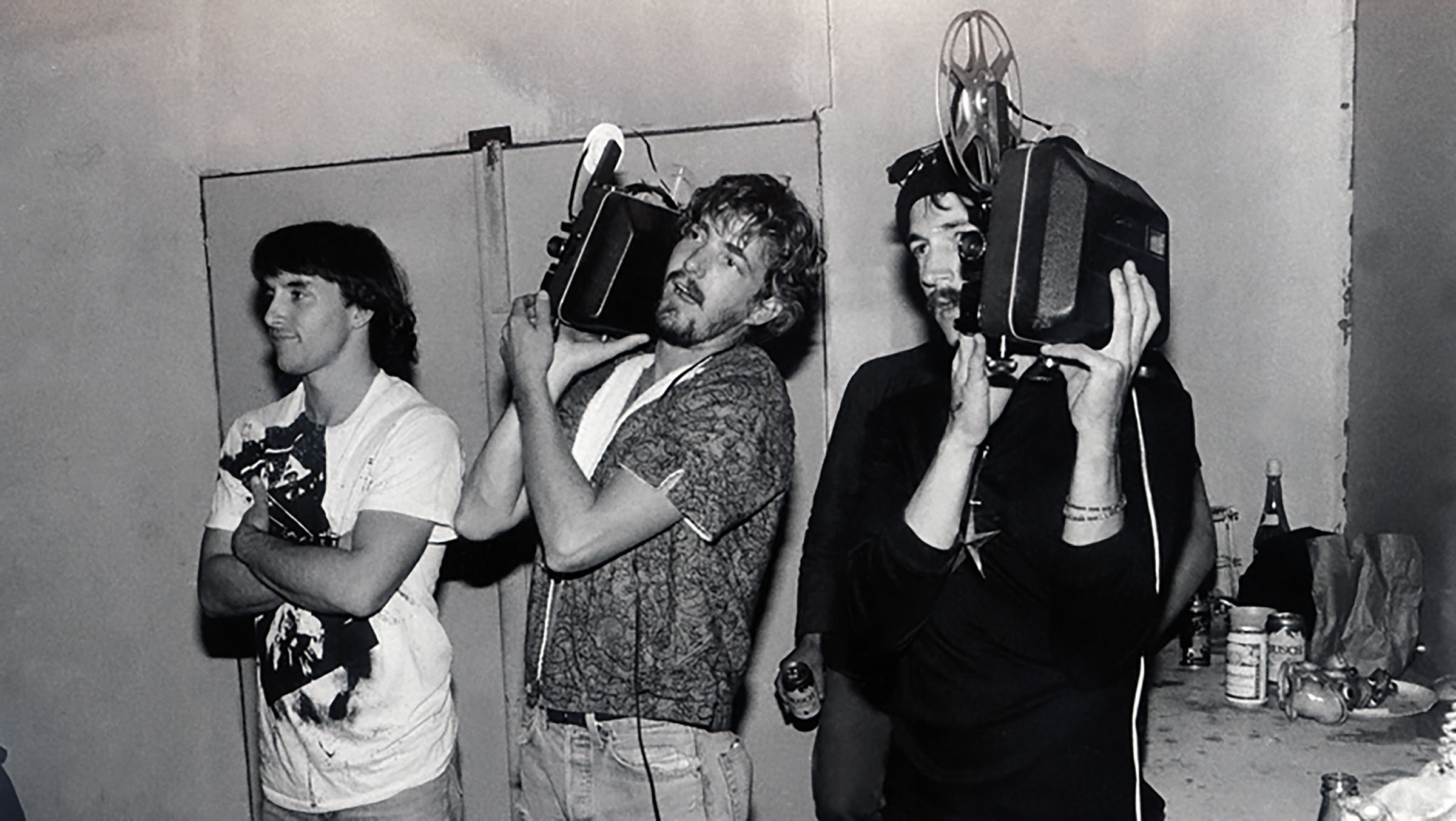

Linklater with cinematographers Lee Daniel (middle) and Bill Daniel in the mid-’80s. Photo courtesy Austin Film Society

Linklater was born in 1960 at Hermann Hospital in Houston. He lived in the city until he was 7, then his family moved to the suburbs. He was 8 when the Apollo 11 mission landed on the moon.

For kids growing up in suburban Houston around then, Linklater recalls, the world was full of indistinct, treeless expanses to ride bikes through, endless housing subdivisions and construction sites to play at, and newly built bowling alleys and movie theaters to escape the heat in. Summer days often meant going to the pool with other kids, cruising through the fog behind the DDT trucks, going to AstroWorld, or taking family trips to the coast. Looking back now with a rose-colored lens, the entire setting seems like one big blank slate waiting to be filled in with a child’s imagination and fantasy. That’s the experience Linklater is trying to capture in the movie.

Of course, Houston in 2020 doesn’t look like the Houston of 1969. Most neighborhoods have trees now. The Astrodome doesn’t look so new. AstroWorld has long since closed. Recreating all of that in the real world would cost tens of millions of dollars. So, in 2018, Linklater’s Austin-based production company, Detour, put out calls for home movies and archival photos of Houston in the 1960s. They received dozens of replies, with hours of grainy footage of AstroWorld, the Astrodome, the young, budding suburbs, and plenty of escapades down to Galveston.

Detour is working with Submarine, a production company based in Amsterdam, to fill the background of every shot with modified versions of those old images as well as the images the production team collected. The result should be a dreamy, nostalgic adventure. It’s unlike anything Linklater has ever done before. It’s unlike anything anybody has ever done before.

This movie won’t be the first time Linklater has pushed the boundary of filmmaking. His most personal movies are, in many ways, about the medium itself. He’s a renowned fan and scholar of film and film history. (A media outlet once asked Linklater to name the 10 movies that influenced him most, and he returned a list of 250 titles, noting, “This is just the beginning.”) He’s also a founding member of the Austin Film Society, a nonprofit for film exhibition and independent filmmaking. Linklater’s movies not only question what a feature film can be; they each do so in different ways.

His first commercially released feature, 1990’s much-celebrated ultra-low-budget Slacker, doesn’t have a plot or a protagonist, per se. It’s a stream-of-consciousness narrative that follows a series of people and conversations around Austin. His next movie, the beloved Dazed and Confused, didn’t have much of a traditional plot either. It follows an ensemble of high schoolers through the travails of the last day of school in 1976. His Before trilogy chronicles the relationship of a man and woman through a few hours of different days, each installment nine years apart. Waking Life, which centers on a young man having several philosophical discussions in an ethereal existence, was the first full-length movie to use digital Rotoscoping. His 2001 movie Tape takes place entirely in one motel room, unfolding in real time. Bernie, about the East Texas murder of a despised 81-year-old millionaire by her 39-year-old companion, repeatedly cuts away from the unfolding narrative to documentary-style interviews with local townspeople. Perhaps most famously, 2014’s Boyhood tells an epic 12-year tale with the actors visibly aging on camera.

Ethan Hawke, who has appeared in eight Linklater films, is one of a handful of actors who are quoted in Richard Linklater: Dream Is Destiny, part of PBS’ American Masters series. Hawke noted the director is “very, very interested in form and content and doing something new.” He added, “Rick is not looking through Hollywood’s eyes, and he doesn’t care how Hollywood sees him.”

Linklater’s movies retain a degree of positivity that most movies don’t. They are nearly all some type of philosophical treatise, a comment on the state of humanity. And while his films can touch on a whole host of dark subjects, the viewing experience is always fun. The takeaway is always hopeful. That’s Linklater.

On the set and in conversation, the director—who turned 60 in July—maintains an even-keel demeanor. He equates the way he deals with actors to the approach of a good baseball team manager. (Linklater played at Sam Houston State University, and the sport is in several of his movies, including a remake of Bad News Bears.)

“Every player needs something different,” he tells me. “Sometimes you’ve got to yell at somebody, and sometimes you’ve got to be super nice to somebody else. Everybody has different needs.”

Matthew McConaughey, whose first movie role was as the eminently quotable Wooderson in Dazed and Confused (“all right, all right, all right”), later starred with Jack Black and Shirley MacLaine in Bernie. In Dream Is Destiny, he is quoted as saying Linklater gives only positive feedback. “He’s redirected me, and I’ve seen him redirect many people,” McConaughey said. “But I’ve never seen him say the word ‘no.’” McConaughey has also said the director is “so Buddhist he doesn’t know that he’s Buddhist.”

Linklater says the set can stay relaxed because of all the hard work that goes into the front end, from extensive rehearsals to the precise details planned for every part of every frame he shoots.

Jack Black received massive acclaim after working with Linklater in both School of Rock and Bernie. He plays the main character, an adult looking back, in Apollo 10 1/2. In Dream Is Destiny, he’s quoted as saying, “When you see his process, you don’t go ‘How the f— does he do it? He’s the f—ing mad genius! If only I could think like he thinks!’ When you see his process, you go, ‘Oh, it’s just hard work.’”

Matthew McConaughey has said Linklater is “so Buddhist he doesn’t know that he’s Buddhist.”

On the day I visit the set in Austin, the crew shoots for more than 10 hours, with only a few breaks. Scene after scene, Linklater is behind the camera or talking with actors or producers. Or he’s working out some final detail with a costume or prop. The actors come and go—there are limits on how many hours minors can work in a day, and personnel on set keep strict track—but Linklater is always there, keeping the operation moving.

Linklater and crew on the set of Dazed and Confused in the early ’90s. Photo courtesy Austin Film Society

After the scene with the couple making out in the Chrysler, there’s another scene of the two boys sitting in lawn chairs at the imaginary drive-in, eating real popcorn, pretending to drink imaginary soda. Everything in front of the camera—from the boys’ clothing, to the lawn chairs, to the popcorn box they’re sharing—is authentic to 1969 Houston. Before the popcorn scene, a production assistant showed the boys clips from Hellfighters, the 1960s John Wayne movie they’re pretending to watch. (It’s also set in Houston.) So worried about accurately evoking the time they’re in, Linklater’s team combed through old newspapers to see which movies were actually playing in Houston that summer.

Later, there’s a scene that includes some of the kids riding their bikes through an imaginary fog behind a mosquito-killing truck. Three adults on the production staff make sure the playing cards slotted into the spokes of the kids’ bicycles are genuine to the time.

“It’s fun to dial in on those details to try to get them right,” Linklater tells me. “That’s what makes you want to be a filmmaker—trying that kind of specificity.”

Following lunch, they film a scene with nine neighborhood children in bathing suits all piled into the back of a vintage 1960s blue Ford Ranger, cruising down the imaginary highway toward Galveston. After one take, Linklater moves one of the fans gusting on the truck—replicating the wind on the highway—to make sure everyone’s hair is blowing in the right direction. (Vehicles have memorable roles in most of Linklater’s films. In addition to the flawless Chrysler and Ranger, Apollo 10 1/2 also features several scenes in an old Woody station wagon.)

While most of the cast and crew periodically sneak away to the craft services tables for a snack, Linklater barely leaves the room all day. A few times, he walks over to a plate of fruit in a chair a few feet from the cameras and has a couple bites of pineapple and strawberry—he’s been a vegetarian since his 20s—but he’s never away for more than a minute or so.

Late that afternoon, they’re shooting a few scenes of the kids playing on the beach. Some pretend to tan. Some toss a football. At some point they chase the imaginary tides and sandpipers. Of course, here, on the soundstage, there is no sand. There is no ocean water. It’s just actors romping about in front of the green walls. Even after a full day on set, standing behind a monitor, watching this pretend family pretend to play on the pretend beach, Linklater is smiling—for real.

He feels the same way a few months later, he tells me, as he’s working through the postproduction, watching and listening for hours every day as the movie slowly comes together. It’s hard for an outsider to know what any of this will ultimately look like when the editing and animation is done. But knowing the director’s career, somehow this elaborate, seemingly chaotic collaboration and technical jigsaw puzzle will eventually become a work of art.

For now, though, Richard Linklater is happy to let his movie take him to a more optimistic time and place.

A Focus

on Texas

Take a journey across Texas and through time by watching a collection of Richard Linklater films. Not all of his movies are set here, but throughout his career the director has consistently managed to depict—often in remarkably specific detail—a variety of locales in our state at various points in history.

Austin, 1989

Slacker

(released in 1990)

Huntsville, 1976

Dazed and Confused

(released in 1993)

West Texas and Various, 1920

The Newton Boys

(released in 1998)

Carthage, 1996

Bernie

(released in 2011)

Southeast Texas, 1980

Everybody Wants Some!!

(released in 2016)

Houston, 1969

Apollo 10 1/2

(coming in 2021)