Hid

den

Fig

ures

Uncovering

the untold

stories

of 3 mighty

Texas

women

By Clayton Maxwell

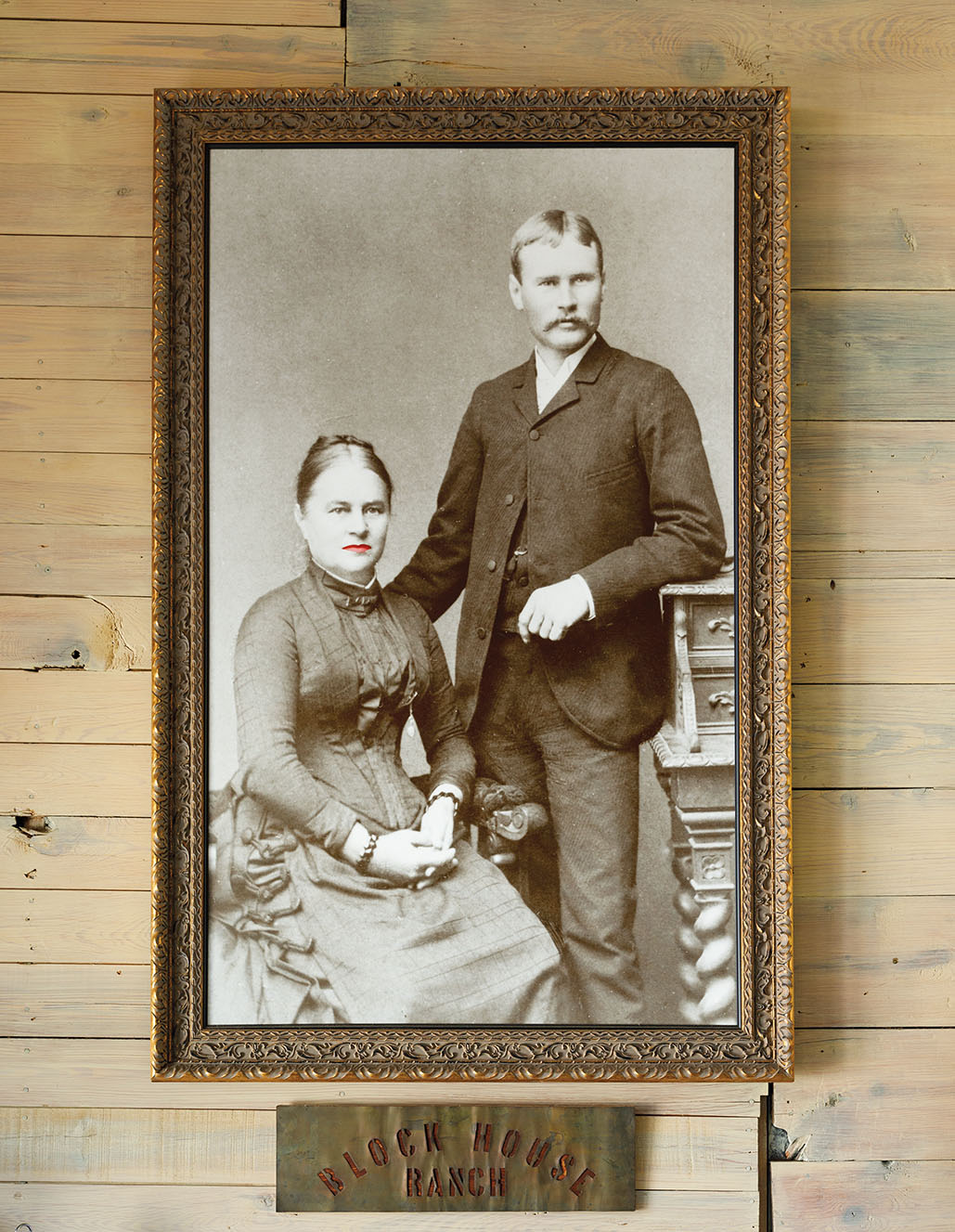

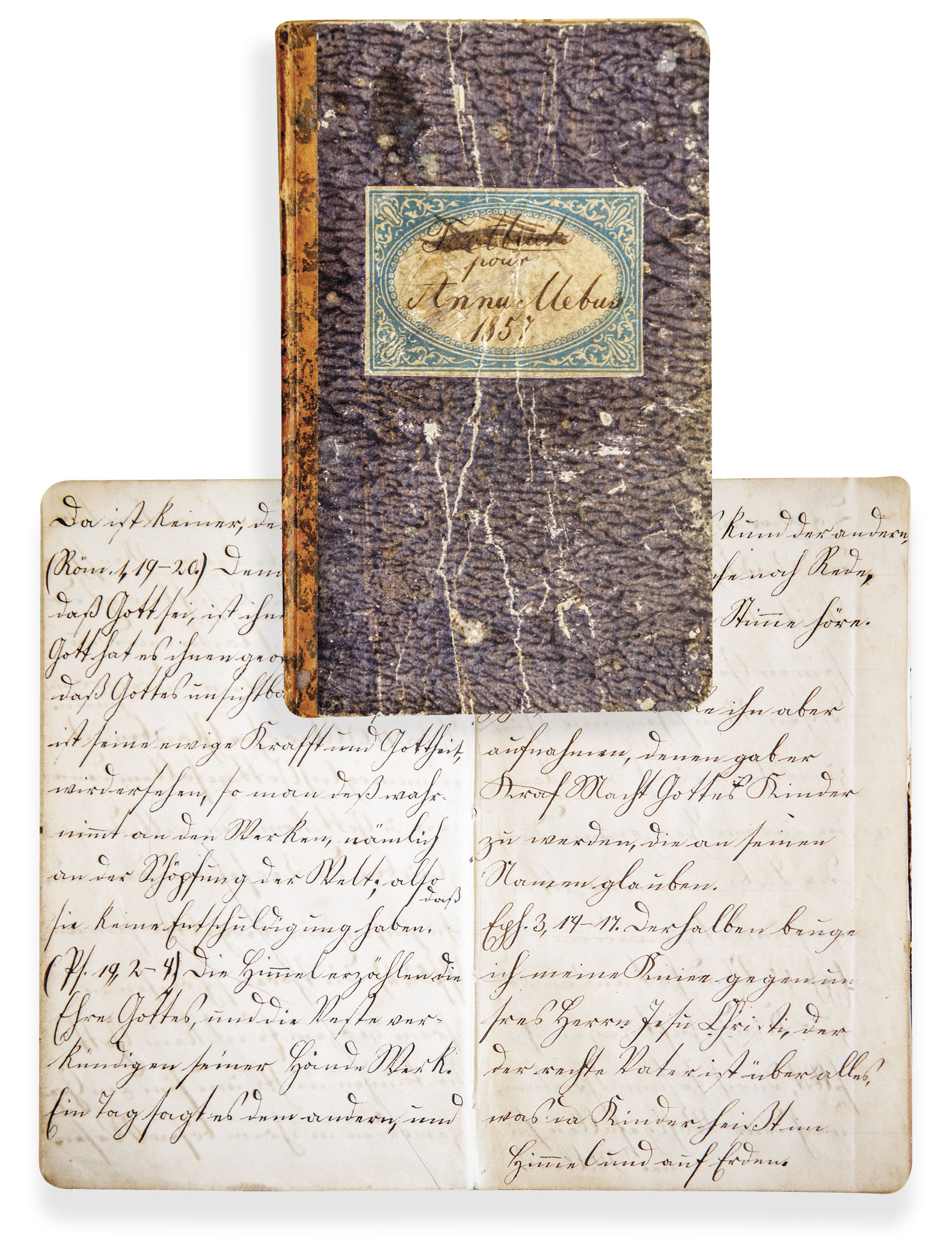

Anna Mebus Martin left her mark on 19th-century Texas. Illustration by Daniel Baxter.

Although Patricia de la Garza de León was the co-founder of Victoria, the town where I grew up, I only recently learned her name. I knew of her husband, Martín de León, the dashing empresario who, in 1824, brought 41 families to the Guadalupe River to build this town, back before there was a Texas. When I was little, my sister and I roller-skated in the town square, De León Plaza, where a marker reminded us that Don Martín is the reason Victoria exists.

Local historians believe this painting, on display at Victoria Preservation, portrays Patricia de la Garza, but they don’t have proof. Photo courtesy Victoria Preservation, Inc.

But it was a surprise to learn about De la Garza (1775-1849), a well-to-do woman from the Mexican state of Tamaulipas who forked over her dowry to finance the Mexican colony that would someday be my home. She hauled her family here to start afresh. Even though she lived on dirt floors, De la Garza got busy erecting the town’s first chapel and school to educate her 10 children, and eventually, dozens of grandchildren. When Don Martín died of cholera in 1833, De la Garza held fast as the matriarch of her family and the town, overseeing social and religious life, making sure children were married and babies were baptized.

De la Garza was the backbone of my hometown. And yet, I’d had no idea who she was. The reasons for this are as twisted up as the times De la Garza lived in. The feminist wordplay from the 1970s rings true: Since history has been “his story,” written by men recording the deeds, wars, and decisions of other men, we have overlooked herstory. Men didn’t make history alone, and scholars, students, and the culture at large are tuning in to these omissions. Texas’ past is full of forgotten people like De la Garza.

“History may get told a certain way, but it’s almost never the full story,” says Nancy Baker Jones, president of the Ruthe Winegarten Foundation for Texas Women’s History, a nonprofit that researches the role of women in the state’s past. “We have finally moved the stories of women more from the margin to the center in the history of the U.S. What that does is give everybody a more complete sense of who we are as a people. It’s especially important for girls to understand that they have shoulders they can stand on, but both boys and girls need to know that women in the past have blazed as many paths as men have.”

De la Garza certainly blazed a path. So did the first female Texas cattle baron, German immigrant Anna Mebus Martin (1843-1925), and the first Black Texan female novelist, Lillian Jones Horace (1880-1965). While modern influential women are more likely to get fair recognition—people such as Barbara Jordan, Kay Bailey Hutchison, Molly Ivins, and Ann Richards—historical figures often slip into oblivion. But each of them smashed barriers and bounced back from defeat to forge a life worthy of a feature film. They rose to the challenge that Martin once expressed in a letter: “I heard men say, O, she is only a woman, but I have showed them what a woman could do.”

Patricia de laGarza

It’s a breezy June afternoon in Victoria, and I am walking through rows of headstones at Evergreen Cemetery looking for De la Garza’s grave with the help of Gary Dunnam, a local history buff. He leads me to a fence surrounding a small family plot, tucked away behind a live oak. Here rest the remains of the De Leóns: Martín, Patricia, and three of their sons—Fernando, Silvestre, and Agapito. In lieu of headstones, state historical markers—placed here in 1972—top each grave. Over De la Garza’s name reads the epitaph: “Pioneer Colony Co-founder and Texas Patriot.” It’s a welcome surprise to see the word “co-founder.” In so many accounts of Victoria’s history, she is absent, but here she gets equal billing.

Seeing the grave, I’m reminded of the words of historian Robert Shook, a retired professor from Victoria College. “Patricia de la Garza is a tragic character,” he told me. “We can only infer what her life was like. Being female in those days, there’s almost no primary source material about Patricia. That’s a sad thing because women carried much of the weight, but no one ever bothered to put it in the records.”

Photo by Kenny Braun

Ana Carolina Castillo Crimm, a professor emeritus at Sam Houston State University, chronicles three generations of De Leóns in her 2004 book, De León, a Tejano Family History. She recounts how Patricia and her children were kicked out of Texas in a wave of anti-Tejano violence—despite their status as the founding family of Victoria. She writes in page-turning detail about their return and the successful court battles launched in 1847 by Fernando, Patricia’s oldest son, to win back land that had been taken in their absence: “At last,” Crimm writes, “a shocked and stunned crowd heard the judge rule in favor of Fernando de León against Andrew White. The precedent had been set. The judge’s gavel came down again and again for Fernando.”

But how did these legal battles impact De la Garza? Without any primary sources, like letters or journals, historians are left to piece together De la Garza’s experiences through secondary documents. The nonprofit Victoria Preservation, Inc., for example, has a transcribed copy of a June 22, 1836, letter from Texas General Thomas J. Rusk to Captain Philip Dimmitt with “an order to remove” the De Leóns from Texas. And Dunnam visited the Texas State Library and Archives, where he found sworn testimonies regarding the treatment of the De León family. He read an account of how soldiers—emboldened by growing anti-Tejano sentiment after the Texas Revolution—tore jewelry from the De León women’s earlobes as they were marched out of Victoria.

We know that De la Garza watched her sons risk their lives fighting against Santa Anna and yet the family was still evicted after the revolution. Even though she spent nine years exiled in Louisiana and Tamaulipas, De la Garza deeded her land on the Victoria town square to the Catholic Church before she died. It’s remarkable that she gave to the town despite her trials, even donating a precious altar vessel that is still in the church today. But De la Garza’s thoughts on these matters are sealed up in this cemetery plot.

Standing at the cemetery gate, Dunnam digs a document from his file and holds it up for me to see. “This tells a story that’s not really told,” he says. It’s a copy of a handwritten affidavit, also unearthed from the state archives, that De la Garza filed in 1849 to recover her land and possessions after her return to Texas. He points to the last page, which bears De la Garza’s name, written in elegant looping cursive with a spiraling rubric at the end. “There’s her signature,” he says. “Now you tell me that women didn’t know how to write.”

There, in distinguished handwriting that’s just a bit shaky, is the most intimate physical record we have from De la Garza: her gorgeous curvy signature signed the very year she died, indicating that she never gave up, not even toward the end. It is so personal, so human, that for a moment it makes her as alive to me as the breeze-ruffled oak tree we stand beneath.

Later that day, I walk through the nave of St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Victoria. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, congregants have only recently been able to re-enter the church. A group of Latina women are spread spaciously among the pews, masked and taking turns reading out loud to each other from the Bible. I wonder if these women know, as I have only just learned, that we are right now quite literally standing upon the gifts of De la Garza, the land she reclaimed and then gave to the Catholic Church. The prayers of these women fill the sanctuary, making it feel outside of time, more mysterious than just a church on a corner on a Tuesday afternoon. It feels like Patricia de la Garza is still here.

Anna Mebus Martin

The San Saba River flows through a ranch Martin bought around 1900 and is still in the family. Photo by Kenny Braun.

Anna Mebus Martin sailed from Germany and landed penniless with her mother and five siblings at Galveston on Dec. 10, 1858—her 15th birthday. Her Uncle Louis picked the family up and hauled them on a two-week journey by oxcart to their new home in a dirt-floor cabin outside of Mason, a Hill Country ranching community on what was then the Western edge of the Texas frontier. Over the next six decades, that 15-year-old girl would amass 50,000 acres, become Texas’ first cattle baroness, the first person in the region to make a fortune from the sale of barbed wire, and the first woman in the U.S. to both found and preside as president of her own bank. And because a man at a New York bank asked her how a woman could succeed in banking, in 1904 she wrote a short “sketch” of her life in reply. Her words are historical gold.

“It was horrible for a young girl, just growing into womanhood,” she wrote of her early days near Mason, “who had seen all the nice things young girls had in Germany, and then taking it abruptly away, in the wilderness of Texas without any future.” She writes of perpetual fear of raiding tribes, particularly on full moon nights. Of losing everything after the Civil War, when Confederate money was worthless. Of watching her husband, Karl Martin, a postmaster who also owned a small dry goods store, succumb to illness while she struggled to support their two sons.

Karl’s death was a turning point for the 36-year-old Martin—a proving grounds for survival. “I had made up my mind that I would either be somebody in life or break down,” she wrote.

She became somebody. She renamed the family store A. Martin & Sons and, with the help of her boys, grew it into a thriving business. She began trading with the travelers who came through, selling groceries, her knitting, lady’s hat bands. But she had a knack for business and was soon selling cattle and serving free whiskey to her customers. Martin began loaning money to friends who were in a pinch. Her success as an informal banker grew into the Commercial Bank, which she founded with her sons, in 1901. The Commercial Bank is still there in Mason; a plaque on the building’s corner salutes her.

“She was determined,” says Andy Smith, Martin’s great-great-grandson, who owns the Lea Lou Co-Op and Lodge in Mason and lives on a ranch that once belonged to Martin. “She came from aristocracy back in Germany, but for a while, when her husband had the little store on the Llano River, she starved. There were stories of her picking corn kernels out of horse crap just because of how poor they were. So, she worked hard. People like Anna, you can give them a little nugget to start, and they’ll turn it into a multimillion-dollar empire.”

Last June, I took my family to an exhibition about Martin at the Mason Square Museum. Relics including a shiny pistol and a violin bring Martin’s life into view, along with a video the Texas Cowgirl Hall of Fame made when Martin was inducted in 2011. My favorite artifact is a poem written by her friend Eugene Frandzen. Titled “Ode to the Llano River,” the poem’s dedication reads, “To Miss Anna Martin, In grateful remembrance of many acts of kindness, this little effort is affectionately dedicated to you.” The more I learn about Martin, the more I like her. Any woman who can wield both a pistol and a violin and inspire river poetry is my kind of gal.

Smith invites us out to stay the night on his ranch on the San Saba River, set on land that Martin bought when it was auctioned on the Mason town square. Other ranchers were going broke from an outbreak of cattle tick fever and had to sell. “Anna could buy it, because at that time, she was the only one around here who had any money,” he says.

As evening falls, my family and I watch a full orange moon rise above the rocky ridge over the San Saba. I tell the kids how Martin had hated full moons because they were ominous preludes to the moonlit raids, when children were kidnapped. My kids are unmoved. The threat, just like the story of a German girl coming to this land in an oxcart, is a distant concept to them right now. But not to me. In this rough wilderness removed from cell towers and civilization, I can imagine the fear. I can also imagine, years after this once-poor widow had become a powerful banker and cattle baron, how Martin would have felt a deep satisfaction watching that fat moon rise.

Texas Trailblazers

Patricia de la Garza is among the historical figures portrayed by actors during Victoria Preservation’s annual cemetery tours. Typically held in late October and early November, this year’s event was postponed due to COVID-19. victoriapreservation.com

Anna Mebus Martin is featured at Fort Worth’s National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, where she was posthumously inducted in 2011. cowgirl.net

Lillian Jones Horace is featured at the Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society, Inc., within the Lenora Rolla Heritage Center Museum on Fort Worth’s Southside. blackhistoricalmuseum.info

The stories of De la Garza and other influential women are highlighted on the Women in Texas History website, a project of the Ruthe Winegarten Memorial Foundation for Texas Women’s History. womenintexashistory.org

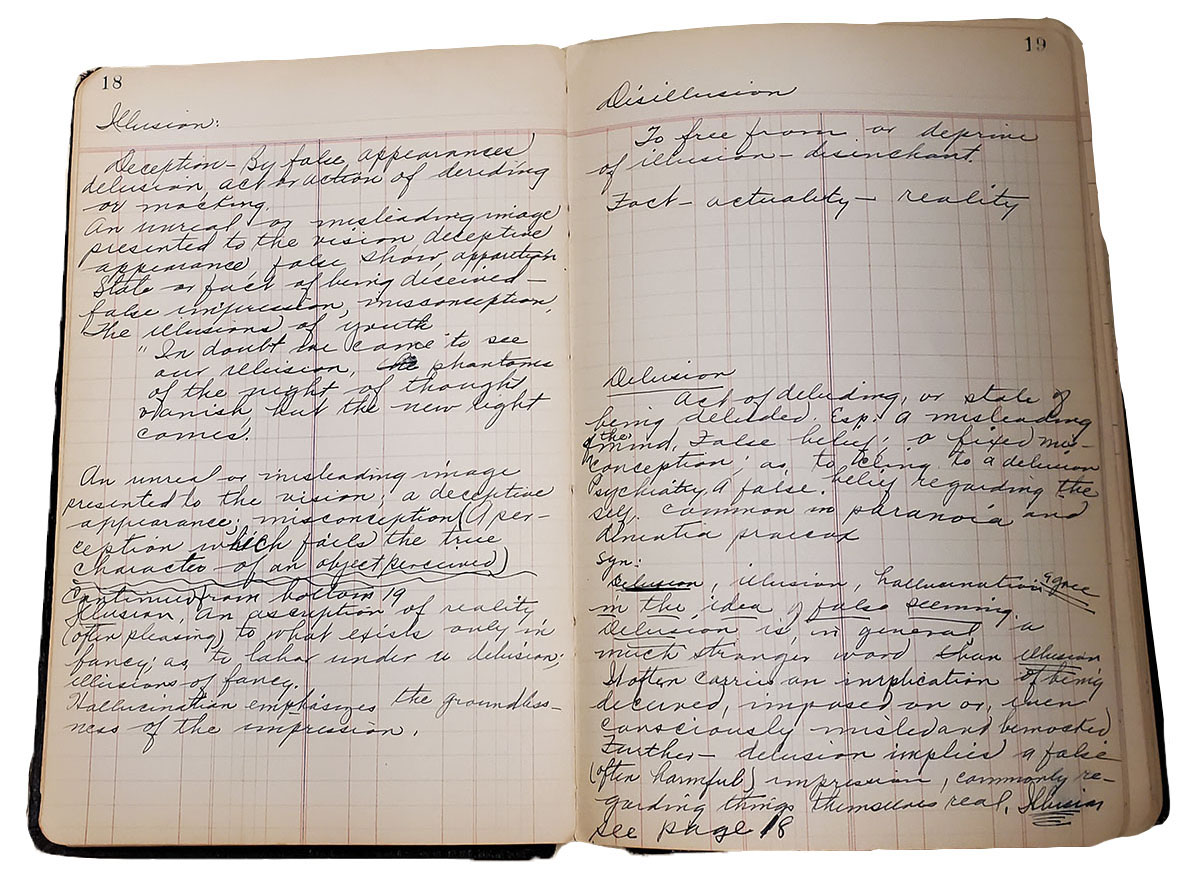

Lillian Jones Horace

An archivist at the Fort Worth Public Library had just finished transcribing the journal of Lillian Jones Horace—the first female Black novelist in Texas—moments before Karen Kossie-Chernyshev walked in the door. Kossie-Chernyshev, who was researching Black Texan writers, says the timing on that day in 2003 was nothing short of providential. A history professor at Texas Southern University in Houston, Kossie-Chernyshev has since introduced Horace not just to her students, but, by publishing Horace’s work and promoting it in academic circles, she has brought Horace to the world at large.

Horace, who was born in Jefferson in 1880 but moved to Fort Worth as a toddler, was a devoted Baptist and intellectual. Writing in the first half of the last century, a time when Texas’ government mandated Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation, she was also a hardworking leader for the Black community, and for Black women in particular.

Her first novel, Five Generations Hence, published in 1916, is a Utopian exploration of a return to Africa for Black Americans. Her second novel, titled Angie Brown and written in about 1949, traces the heartbreak and victories of a young Black woman finding her way in the Jim Crow South. “We see her using Angie’s life to show that if you do things a certain way, you’ll be OK in spite of obstacles,” Kossie-Chernyshev says. Horace had no luck getting Angie Brown published in her lifetime; it was not until Kossie-Chernyshev published it in 2017 that the novel was available to the public.

Horace was a voracious learner devoted to the power of education. She received multiple degrees and was valedictorian at Prairie View A&M University. During the summers, she attended programs as far afield as the University of Chicago. In the early 1900s, as a teacher at the segregated I.M. Terrell High School in Fort Worth, she launched the first school newspaper and library. She also campaigned for Bob Thornton, the first African American to run for city council in Fort Worth.

Horace’s diary is in the archives of the Fort Worth Public Library. Photo courtesy Fort Worth Public Library Archives

Horace’s journal, still in the archives of the Fort Worth Public Library, is a treasure. It’s a portal into her interior landscape, and so full of self-reflection and questions about race and history that you can feel her curious heart beating through its pages. I can relate, with dizzying appreciation, to her desire to understand words, the world, herself, and to be a better writer. “I want to write realistically but constructively,” she notes. “I must see the fineness even in the rogues.” Her rough notes span from the philosophical—“All life is experiment”—to the practical—“I did achieve the big thing I planned, that we should possess our home free of all mortgages.”

And then there are the sections of her journal that are heartbreakingly foreign to me, the pages where she works through her frustration over her everyday experiences as a Black woman. She ruminates on how her classmates at an integrated college, while friendly, still gave her funny looks. She records a painful experience at a Fort Worth department store. “The white woman steals shoes from me at Stripling’s,” she writes. “The floorwalker, Mr. Weed, hurts my feelings. I lie awake and suffer much of the night. I ponder what to do, I want to say things to him, not vulgar things but things to show how inconsiderate he was in a crisis. The first time I feel unpatriotic—just a dark face makes you the recipient of any insult.” These jottings are a glimpse into the private, internal pains of racism.

Horace was also a zealous and comprehensive list maker, recording everything from her Christmas gift shopping to civic duties on the World War II homefront. My favorite list, titled “What do I really want?” is a touching inventory of her desires: “I want sincere friends—all ages,” and “I want more than any tangible thing to write a book worth the reading by an intelligent person.”

Historian Karen Kossie-Chernyshev. Photo by Kenny Braun.

Kossie-Chernyshev has certainly furthered those goals. Not only did she publish Angie Brown, she also directed the republication of Horace’s earlier work, Five Generations Hence, accompanied by critical essays from other scholars of Black literature and history.

“Perhaps my finding her archives was a response to a prayer Horace had that eventually her work would be appreciated,” Kossie-Chernyshev says. “I do what I do in honor of her memory. Sometimes our answers come from people who are no longer here. She is a friend that I didn’t know I had.”

Kossie-Chernyshev says Horace’s work has driven her to overcome her own challenges, and by bringing Horace back to life for a wide audience, she’s sharing that inspiration with people like me. Perhaps that’s the underlying message found in the stories of pioneering Texas women like Patricia de la Garza, Anna Mebus Martin, and Lillian Jones Horace. We see parts of ourselves in them, and we imagine how we too can rise above circumstance to live our own remarkable lives.