A

Tale Of Two Dickens

An Englishman embraces Victorian London at the Strand in Galveston

Story and illustrations

By Edward Carey

The first person we saw upon entering The Strand in Galveston was Charles Dickens. It was an early December afternoon in 2021, and this was something of a shock, as Dickens died in 1870. On closer inspection, the beard of this Dickens, not the famous English writer, may perhaps have been a little overwaxed, and he was perhaps a little short. But even so, there was the fellow in the flesh still in his old Victorian togs. How else would we know him? I refuse to fathom Dickens in a Stetson.

Something strange was happening: Dickens was being interviewed for a local television station. We said to ourselves, Let it be true; Dickens has come back to us. My teenage son, Gus, and I had traveled from Austin to Dickens on the Strand, a three-day, Victorian-era role-playing festival held annually in Galveston’s historic district during Christmastime. Dickens was famously disillusioned with America, finding it a place of cruelty and greed. “I am disappointed. This is not the Republic I came to see. This is not the Republic of my imagination,” Dickens wrote in American Notes, a travelogue of his trip to the United States in 1842. But Galveston has never quite felt like America to me. It always seems as if it’s somewhere else altogether. So, perhaps Dickens may not have minded it. The locals seem not to be offended, for the 2022 Dickens on the Strand, Dec. 2-4, is the 49th annual.

Gus and I love Dickens and had reread A Christmas Carol before we set out. “Dead as a doornail,” we said to each other. “Bah! Humbug!” and “God bless us, every one.” And now here, before us, was the man—well, as played by T. Stacy Hicks, an actor who lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Hicks has worked for three decades at Renaissance fairs portraying real people from history: William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Robert Dudley, and the earl of Leicester. He’s also portrayed real people from the American Revolution and the Civil War. First-person historical portrayals were nothing new to him. Still, he was nervous to play Dickens. “I mean, his name is right there in the title of the festival, so I really wanted to get it right,” Hicks said.

But he need not have worried. People spotted him immediately, he said. “I knew that if they recognized me before I even opened my mouth then half of my work was done already,” he said. “It also helped that I was staying at The Tremont House, so I literally walked out of my room in the morning as Mr. Dickens.”

The Strand is a downtown district between 20th and 25th streets, fronting Galveston Bay, with antiques stores, art galleries, and souvenir shops. It’s a National Historic Landmark District whose architecture dates to when Dickens was writing in the mid-1800s. As we stood with Dickens, the costumed public filled the streets. Watching these Victorian ghosts before us, I considered the business of dressing up. Of putting on clothes from a different time. Of pretending to be someone else. We’re all ourselves every day, but it is wonderfully refreshing to exist as someone else for a brief while. Gus and I are not ones for dressing up and remained happily and dully contemporary.

What a thing it is to physically consider history, if only to know it by the feel of a corset or a hoop skirt, or by the weight of a top hat. People poured in all around us in period dress. Chelsea Pensioners wherever you looked; redcoats pottering by. There were any number of top hats, so that at a certain elevated angle you could witness an etching by the French artist Gustave Doré—the greatest illustrator of Victorian London—come to life showing the chimney pots of some London tenement. Among the street performers, we spotted the famous English clown Grimaldi, dressed precisely in the 1802 costume for his most famous recurring character, Joey.

In a moment, bagpipes were playing—this is not strictly Dickens, of course, but the noise of Scotland. A few minutes later, Gus and I stood, full of wonder, before a gentleman playing the old Scottish tune “Bonnie Banks o’ Loch Lomond” on an assortment of wine glasses. We turned a corner to meet the familiar noise of Christmas carolers: “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen,” “Silent Night,” “O Come, All Ye Faithful.” Here was Christmas, and here was a new London before us. In Galveston. In America.

We are fed Dickens at a young age in England,where I was born and grew up. It’s something like Marmite—you like it, or you loathe it. I have always loved it. During lockdown, unable to travel back from our home in Austin, I’d find England in the pages of Dickens. One of the other solaces for me and my family during the pandemic was escaping to Galveston.

We have always been drawn to the place, its architecture and history, its ocean, its pelicans and dolphins, and its strange, haunted atmosphere. Arriving on the island, I feel that I have come to somewhere foreign. There’s nowhere quite like Galveston—it’s a part of America, of Texas, but it remains stubbornly itself. Galveston is alive and dead at the same time. You feel the past so palpably walking its streets: the old Victorian buildings; the unbearable destruction caused by, among other storms, the Galveston Hurricane of 1900.

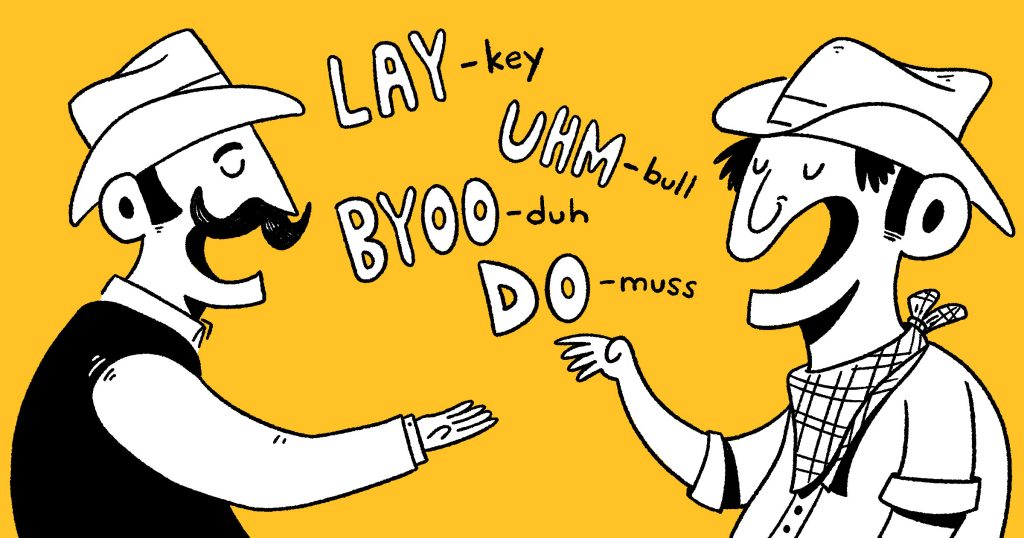

The atmosphere is so distinct, a pelican appears not unlike a Dickens character. It moves with its chest puffed out and a determined swagger rather like Mr. Bumble from Oliver Twist or Pecksniff from Martin Chuzzlewit. A brace of roseate spoonbills might very well be cast as Mr. and Mrs. Veneering from Our Mutual Friend. It does not take much imagination to see some unhappy Dickensian mollusc dwelling inside Galveston’s old buildings, some of them in very dramatic states of disrepair: a Mrs. Gamp, a Quilp, a Mr. Pancks.

On Galveston Island there are also semblances of Satis Houses, where the jilted Miss Havisham—decaying in her wedding dress, never leaving her home—lives in Great Expectations. The 1892 Bishop’s Palace might pass as Chesney Wold from Bleak House, home of the affluent Lady Dedlock family, and there are many unhappy dwellings that might double as the slum Tom-All-Alone’s from the same novel. Or perhaps the tall ship Elissa might be mistaken for the packet ship in Great Expectations, or even the vessel in which Martin Chuzzlewit sets sail for America, or the one used by the Micawbers on their way to Australia.

Dickens on the Strand originated as a community-focused potluck that was designed to bring awareness to The Strand. Back in the 1970s, the area needed significant work and was not a tourist destination in any form. “Essentially, it was a preservation effort,” said Will Wright of the Galveston Historical Foundation. “Dickens on the Strand works so well on so many levels. It acknowledges our architectural history, offers local businesses an early December bump in sales, and is something that the residents have a real connection with. It’s a generational event for so many.”

Here before us, on The Strand and Mechanic Street, was Victorian London reconstructed. Lord’s Cricket Ground, Marble Arch, Westminster Abbey, Trafalgar Square—all of them clearly labeled. But not everyone here was strictly Victorian. There was a definite stream of steampunk and a few fairy wings crashing the party. “It’s like a drunken collaboration between Dickens, Walter Scott, and Jules Verne,” Gus said.

All were welcome, and for a small portion of time here was England. Here was London as I had never known it. As if this was a madhouse London created by someone who had never actually seen it. Rumors of London! As if here was all that remained, this false city, this Never London, this simulacrum. And yet is that not in the spirit of theater—to which Dickens was dedicated to all his life and for which he went to an early grave after exhausting himself by giving so many dramatic public readings? In the theater you must merely state, “We are in Denmark, Scotland, Venice, Ancient Rome, Ilyria”—and it is so. If a person says they are Richard III, Cleopatra, Puck—then it must be believed.

“How can this be London?” I asked myself. And yet I realize Texas is also home to these cities: Bogotá, Buda, Dublin, Liverpool, Moscow, Newcastle, Odessa, Praha, Paris. So why not London in Galveston?

Everyone about us believed and was in great good cheer, the more so because now at last everyone could be together again after another wave of COVID. Some businesses in The Strand had not made it through the pandemic. I conversed with one barman who pointed across the way at a spot formerly occupied by people who had an alpaca farm and sold clothing made from the animal’s wool. By the wave of his hand, I imagined a ghostly alpaca, something like a pantomime horse.

And then, newly arrived upon The Strand was Queen Victoria. She lacked an adequate corpulence, and she wore a tiara and not a crown—and it was fashioned of plastic—but we went along with it. A Christmas Carol, after all, is one of the few times when Dickens fully embraces the fantastical. Impossible things happen. Ghosts come to talk to Ebenezer Scrooge. Spirits show him his various selves: a child, a young man, a middle-aged man, even a dead man, all the ages of Scrooge. And so, it must be considered a piece of wonder to see people, ordinary everyday people, dressing up, putting on crinoline and bombazine, waistcoats and wigs, and parading in the streets.

There was a street urchin gnawing on a turkey leg; a suffragette with a funnel cake; a perfectly adorned policeman—a peeler, a bobby—and his pint of porter. Hand bells, juggling, fencing, troubadours, puppet shows, costume contests—a circus! And some rather more specific entertainment: Albert’s Whisker Review—a competition of facial hair; Christmas Tea with Mrs. Dickens; Pickwick’s Lantern Light Parade; the Dickens Dash (a race); the Queen’s Parade. And you might visit, for example, Tiny Tim’s Playland and Petting Zoo or Fezziwig’s Beer Hall or Ebenezer’s Festival Retail. Over there, look, a man in a nightshirt and cap selling beer at a stall very closely resembled the haunted Scrooge.

In a shop on the Strand, Gus and I heard another English voice. I had read in the brochure that a descendant of Dickens would be at the festival. I wondered if just in front of us at the head of the queue was one Oliver Dickens, great-great-great-grandson of the famous novelist, buying a bottle of water. When asked, he freely admitted it, and so here on The Strand in Galveston was the actual blood of Charles Dickens. Gus and I could not quite believe it. I couldn’t help but think of Peter Pan asking the theater audience to save Tinkerbell—if they believed in fairies—and the audience must respond by clapping in true belief. I do believe in fairies. I do, I do. We did believe in Dickens on the Strand. We did, we did.

Oliver sensed Galveston appreciated what his great-great-great-grandfather represented.

“I would like to think that Dickens has revealed that all people are different, have their own stories and memories, think differently and have differing views—but whom all live on the same earth and therefore deserve the same hospitality and grace from their fellow man,” Oliver told me. “I quote from my own reading of A Christmas Carol: ‘I have always thought of Christmas-time…as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.”

“I would like to think that Dickens has revealed that all people are different, have their own stories and memories, think differently and have differing views—but whom all live on the same earth and therefore deserve the same hospitality and grace from their fellow man,” Oliver told me. “I quote from my own reading of A Christmas Carol: ‘I have always thought of Christmas-time…as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.”

That Saturday afternoon, and the day following, this very genuine Dickens on the streets of Galveston read, in precisely the tradition of his relative, A Christmas Carol. Dressed in Victorian clothing—a smart tailed suit, waistcoat, and top hat—his performance was wholly splendid. Oliver was professionally trained as an actor, and his reading was a master class. He had the pages before him, but they seemed almost entirely memorized. And Gus and I sat and listened to Dickens read by a Dickens, and we were there with him absolutely.

Afterward, we walked The Strand with its long history, with its bars and shops, with its giant sculpture of a trumpet and its mural to Juneteenth, and we mingled with the costumed people and watched all the colorful business before us. We felt we had traveled countries and centuries, and we were here, and we were there, all at once and together again after such a long absence.