The building had most recently been used to store dog food for the Howard County Humane Society, which attracted the vermin. What drew me, though, was the small wooden clump of a stage where Corsicana native Lefty Frizzell invented a new, syllable-stretching way to sing country music in the late 1940s. As the former Ace of Clubs, this decrepit structure at 2605 W. Highway 80 in Big Spring is a shrine of Texas music, as important to the development of the honky-tonk sound as Liverpool’s Cavern Club was to the British Invasion. George Jones, Willie Nelson, and Merle Haggard are among the many legends who have acknowledged a debt to Frizzell’s jazz-like phrasing. I stood there, in that place where it all started, for a long time, letting the space inhabit me as much as I did it.

Long-dormant clubs used to be dead to me. I wanted to be where the action was, where the music roared and the spirits flowed. Before I devoted myself to history, I was prone to hysteria, as a rock critic in love with the notion that opinion can’t be proven incorrect. There was no right or wrong, only interesting or boring. I could be outlandish or just like everybody else. I was tagged a contrarian, with which I totally disagree. I considered myself more like a roast comedian with a backstage pass.

But zingers don’t linger, and these days I’m a tyrant only to my tires. It wasn’t until my mid-40s that I realized nothing makes me feel more alive than telling the stories of the deceased musicians whose influences still reverberate today.

When I was a young writer, I didn’t really know anything so I relied on a fearless attitude to get folks to read my stories. But with age and experience comes knowledge that can entertain in a much more satisfying way. And history has a very definite right or wrong. Making sure your information is accurate requires a work ethic akin to, as Kurt Vonnegut described the writing discipline, inflating a blimp with a bicycle pump. Anybody can do it, but many people give up when the effort seems futile. Sometimes obsession is the talent.

The negative things in your life eventually become positive if you give them time and mileage. That’s another thing I had to learn. In April 2000, the Austin American-Statesman, Austin’s daily paper, announced—very publicly—that it was suspending my barb-laden local celebrity column, mainly because the brass felt the tone was mean-spirited. I was wrecked, humiliated. My editor was sympathetic, taking me aside and suggesting that I use the effort previously devoted to three columns a week for one substantial piece. “Take your time and write the story you didn’t have the time to write,” she said. “Travel if you have to.”

Incidentally, a few weeks prior, I had made an exciting discovery. In the liner notes of a CD reissue, I found that Rebert Harris, perhaps the most influential male gospel singer of them all, was still alive. He was from Trinity, 88 miles north of Houston, though he’d lived in Chicago since the ’40s. In the summer of 2000, I redeemed my Statesman shame coupon to fly up there to interview the frail 84-year-old who taught the famous singer Sam Cooke, his replacement in the Soul Stirrers gospel quartet, how to make lyrics more elastic. Cooke’s trademark woah woah woahs from “You Send Me” started as an improvisation when he couldn’t hit the old man’s highest notes.

Before I devoted myself to history, I was prone to hysteria, as a rock critic in love with the notion that opinion can’t be proven incorrect. There was no right or wrong, only interesting or boring.

My interview turned into a visit. Harris had just had a stroke and didn’t talk much, so there wasn’t anything to build a story around. Except that inside this little, hunched-over man was the voice that practically invented soul music. Harris passed away a few weeks later and when The New York Times obit, which didn’t come for six days, contained inaccuracies and understatements, a new chapter in my career started. I had to do everything I could to correct this injustice and elevate the stature of the gospel pioneer whose death caused barely a blip in the music press.

I headed to Trinity without knowing a soul in town. Just drove cold to that tightknit community at the tip of Lake Livingston and looked for folks who may have known the great gospel singer. I approached a couple of elderly African American men in coveralls at the general store and said I was writing a story about Harris. Did they know him? Within 30 minutes I was in the annex of a Baptist church. Services had just ended, and I was talking with people who grew up with Harris. I met former classmates and neighbors, and even a member of his first gospel quartet from 1923. That member, Hill Perkins, told me Harris was so small he had to stand on a chair to lead the older boys at his father’s Harris Chapel CME. Even at age 7, everyone knew he had a special talent, born from mimicking the birds on his family’s farm.

I had hit a home run in my first at bat. But there would be many strikeouts, pop flies, and foul balls in the next 20 years of trying to tell the stories of musicians I considered criminally overlooked.

Driving is meditation with a seatbelt, and I use that time on research trips to try and solve mysteries in my head. After my first book, All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music, came out in 2005, a writer for The Times, in London, called it “the work of a rock and roll detective.” It’s a cool quote that will adorn the back jacket of my next book, Ghost Notes: The Pioneering Spirits of Texas Music, coming out in April.

But my conclusions are often built on the sketchiest evidence because that’s all there is on little-known artists, often poor and marginalized, who passed away decades ago. Sometimes the rundown houses and venues of their pasts—and the music they left behind—are the only proof they ever lived at all. So I like to bask in the dusty auras and commune with the ghosts.

I first became aware of vintage Texas gospel music in 1996. I was preparing to write a story about Fort Worth superstar Kirk Franklin and God’s Property, a Dallas community choir that had an unlikely No. 1 hit on the pop charts with the hip-hop-infused song “Stomp.” I needed some background in religious music, so I bought a couple of books on the history of the genre. I got a real education on how the songs the slaves sang in the fields evolved into “the Christian blues.”

Among my many discoveries was that “Nobody’s Fault but Mine,” which I knew as a Led Zeppelin song, was written and recorded by Blind Willie Johnson of Marlin, near Waco, in December 1927. On that same weekend, in Dallas, Columbia Records recorded the curious, zither-playing East Texas preacher Washington Phillips. Beating these two otherworldly musicians to the studio by 18 months was Sherman piano thumper Arizona Dranes, a direct influence on Thomas A. Dorsey, considered “the Father of Gospel Music.”

After hearing their raw, passionate music, I became infatuated with that holy trinity of 1920s Texas gospel musicians. I did the research and writing on CD reissues of Dranes and Phillips, both nominated for a Grammy as best historical album, and wrote the liner notes for a Johnson tribute album featuring such gospel fans as Tom Waits and Lucinda Williams. It’s taken me 15 years, and counting, to correct all the misinformation on Dranes, Johnson, and Phillips.

My editors at the Statesman were always pulling me off my stories to work on breaking news. I received such a call the morning I confirmed that the Washington Phillips who made such haunting recordings as “Denomination Blues” and “What Are They Doing in Heaven Today” had been confused in biographies with a tragic cousin of the same name.

“Sorry, can’t do it,” I said. “I’m on my way to Freestone County.” The editor insisted I come back to Austin to write a front-page story, but there was no way. I lied and said I was already past Mexia, when in actuality I was still in Austin (on Research Boulevard, suitably). My superiors were ticked off for a couple days, but I eventually got my Phillips story. He didn’t die in the state asylum in 1938, as previously believed, but lived and preached and sang until 1954.

Delusion was a great motivator for me and fueled the long drives with big hopes. I envisioned finding a wooden chest with photographs, posters, an old guitar neck.

Delusion was a great motivator for me and fueled the long drives with big hopes. I envisioned finding a wooden chest with photographs, posters, an old guitar neck. Maybe I’d stumble upon a long-forgotten venue where the magic was honed. But I almost always headed home a few days later with only the slightest new info: an old address, a marriage license, a foggy remembrance from a second cousin. Nothing is still something, though. You cross it off and move on to the next thing.

There’s a ton of info online, but to really tap into the spirit of the subjects, you have to walk where they walked and talk to those who knew them—a quickly disappearing group. There’s a thing I call “traveler’s memory,” like how I can’t remember what I had for breakfast today, but can recite my order from Cookie’s Place in Teague, when I went there for the Phillips story 14 years ago (beef tips and rice, fried okra, iced tea). Your mind takes note of things on the road it may miss at home. But there are also hours when all roads look the same.

Driving all across Texas is like eating a large pizza by yourself. Three slices go by like San Antonio in the rearview mirror, and you wonder if large is going to be enough. But at about the fifth or sixth slice, you’ve had enough. On the occasions that I-10 is close to becoming “I quit,” I lay awake in that night’s Motel 5 ½ and wonder if it’s all worth it. But I always wake up hungry for more.

I’m sure South Padre is nice, but my kind of vacation is to drive to Brookshire Brothers towns so I can check in at the county clerk’s office and run my right index finger over dusty documents. Then I knock door to door in poor neighborhoods looking for someone who knows something. Doesn’t that sound like the worst Corona beer commercial ever?

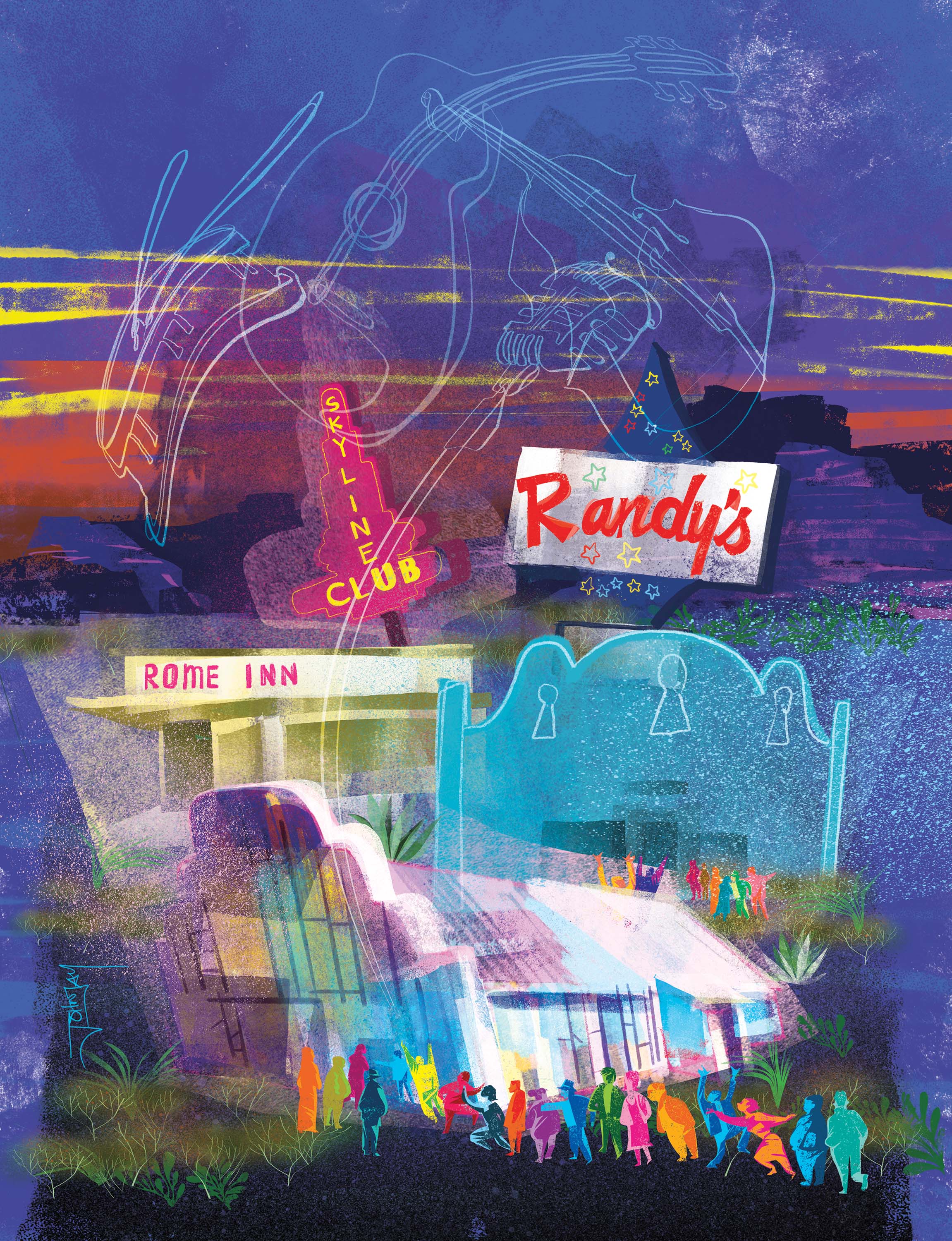

Visiting the vestiges of our state’s rich musical history is, at 64 years old, my beautiful sunset. In San Antonio, I’ve explored Don Albert’s Keyhole Club, the first integrated nightclub in the South, and Randy’s Rodeo, site of an infamous 1978 Sex Pistols concert. They’re currently a rental hall and bingo parlor, respectively. If I’m within a quarter tank of Wichita Falls, I’ll drive to the former site of the 13,000-square-foot MB Corral (currently The Hangar), where Fats Domino, Elvis Presley, Bob Wills, Ike and Tina Turner, and many more performed. In Dallas, there’s the recently restored Longhorn Ballroom, once managed by Jack Ruby, and in Longview I visit the former site of the Reo Palm Isle (est. 1935). The Palm Isle was the Club V disco last time through, but no amount of thumping bass can drive away the phantoms of Frank Sinatra, Loretta Lynn, and Glenn Miller from back in the day. When I told a young couple sitting outside the old Palm Isle a couple years ago about some of the legends that had graced the stage, the woman said, “What stage?”

She didn’t care—most folks don’t—but my mission is to try and make others, through my research and writing, realize the treasures that are out there, just barely holding on. Injustice motivates me. “Why aren’t these influential musicians more famous?”

I have nothing against blues guitar giant B.B. King, but T-Bone Walker of Linden invented most of the riffs King took to mainstream success, and he deserves higher recognition. Same goes for Houston’s Illinois Jacquet, whose 64-bar tenor sax solo on Lionel Hampton’s 1942 hit “Flying Home” was the foundation for the honking sax style that would dominate R&B solos in the 1950s. More people need to be aware that East Texas singer Ray Price saved country music in the heyday of Elvis by inventing the country shuffle with the 1956 song “Crazy Arms.”

I think often about when this journey started two decades ago with a visit to Trinity, but it’s not nostalgic yearning; it’s a sinking feeling. I ended that article on Harris with the memory of my last reporting trip to the town. I was at Harris Chapel, the small, white, wooden church on State Highway 19. It was locked, so I sat in my car and listened to Harris and the Soul Stirrers on the CD player for a long time, imagining that this glorious music was coming from inside. It all started right here: Rebert Harris to Sam Cooke to Aretha Franklin, the evolution of gospel to soul. How ’bout that?

The truth, however, is that I’m not sure that was the CME chapel where Harris started singing in his father’s congregation. African American churches sometimes dropped the denomination over time, so I just went by the name Harris Chapel and made the connection. The county clerk’s office was closed, and I was heading home, so I was unable to verify that this white wooden church, at this location, was owned by James Harris in the 1920s.

This most likely was the right spot, but that’s not good enough for history. I need to revisit Trinity and confirm the landmark location. I’ll do it on my next empty calendar square. I’m always updating, I’m always double-checking, I’m always looking somewhere I didn’t look before. Even after your work is published, the job is never done.

Back in my rock critic days, my dream was to discover the next big thing playing in some dive in front of 15 people. But in recent years, I’ve delved into musical acts that readers have zero chance of ever seeing live. That’s why I was thrilled to learn that the old Ace of Clubs in Big Spring, where Lefty Frizzell changed country music, has been preserved and is set to reopen soon. It’s great when the ghosts can hang out in their old haunts. They’ve earned it.