A farmer rakes up fallen pecans at Berdoll Pecan Farm; Swift River’s in-shell pecans.

Deep Roots

The story of Texas’ favorite nut,

from planting to pie-making

By Laurel Miller

Photographs by Jessica Attie

The metal arms of a hydraulic shaker clamp around the trunk of a mature pecan tree, performing a high-speed vibrato lasting nearly a minute. The ripe nuts hit the ground like shrapnel while the violent quivering of the leaves sounds like hail on aluminum shingles.

At Swift River Pecans in Fentress, just outside Lockhart, Troy Swift and his crew are putting in another long day harvesting pecans. Here in Central Texas, the state’s pecan epicenter, harvest starts in October and lasts through early January. Each tree is shaken once, and the pecans are collected from the ground by machine and taken to the company’s cleaning plant.

Troy Swift picking pecans

Swift River is just one of many pecan orchards keeping this integral nut on Texas tables. Pecans’ ubiquity in holiday dishes, barbecue pits, and backyards across the state makes it easy to take them for granted. But crack the shell, and you find a story of the state’s economy, anthropology, agriculture, and aesthetic writ large.

The Pecan Belt extends from northern Mexico to northern Illinois. Pecans, one of the only major tree nuts native to North America, are now grown in 15 states. Texas is the nation’s third-largest producer, after Georgia and New Mexico. By the early 20th century, pecan cultivation was so widespread and successful in Texas, the state Legislature designated the pecan tree as the official state tree. Around this time, the Hill Country town of San Saba declared itself the “Pecan Capital of the World.”

“In a good season, the Texas pecan industry will produce about 50 million pounds of nuts,” says Bob Whitney, executive director of the Texas Pecan Board.

While pecan farming in Texas is mostly a family business, Swift took up the trade as a second career and has become a respected grower and industry expert.

Swift and his wife, Athanasee Swift, started farming in 1998, after he transitioned from a career in manufacturing. Two years after purchasing 66 acres by the San Marcos River in Staples, Swift planted pecan trees hoping they would bear nuts by the time he reached retirement age. Today, he owns two thriving orchards that produce 14 varieties of hybrid pecans and wild native pecans, as well as a busy sawmill. The mill yields lumber from pecan and other hardwood trees, which are coveted by furniture makers and other craftsmen. The extra income allows Swift to retain his employees year-round.

The wild pecan trees here are of the Carya illinoinensis species, which is indigenous to the Pecan Belt. Some are more than 200 years old and 100 feet tall. “I like working with trees, being in the orchard, and the science behind it all,” Swift says. “But it’s also about being in nature.” Indeed, the farm is like a natural cathedral, all filtered light and silence save for the crackle of footfalls and scuffle of small animals and birds. At the edge of Swift’s Fentress property lies an improbably green river. A combination of well-draining soil, sun, and moisture provides the ideal environment for pecan trees to thrive, which is why most Texas pecans are grown in or near river valleys.

From Fossils to Family Farms

The banks of the Rio Grande have yielded fossilized pecans estimated to be 65 million years old. Based on archeological evidence, pecans were an important source of dietary fiber and monounsaturated fat for Native Americans in Texas 5,000 or more years ago. “Pecan” is a corruption of the Algonquin word pacane, a nut requiring a stone to crack its shell.

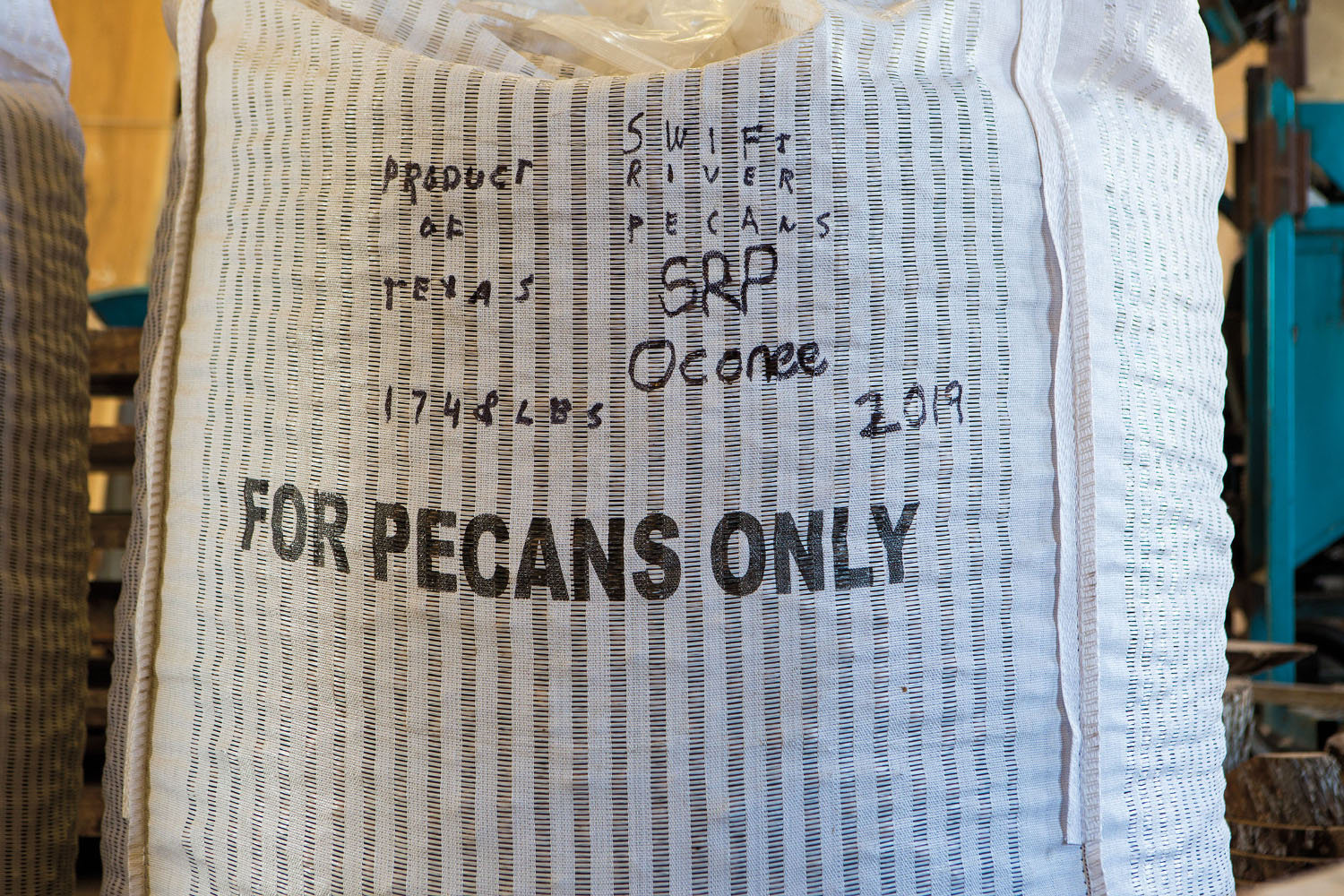

A bag of Oconee pecans

“The earliest records of our people talk about the importance of the pecan as a food source,” says Ramón Juan Vasquez, executive director of the American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions and a member of the Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan nation.

Vasquez notes that pecans, mesquite, and prickly pear were the native foods of the Coahuiltecan, and that Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca wrote of the nuts extensively in his 1544 memoir, La Relación, after he saw how they sustained the native peoples on his travels through Mexico. “There’s a reverence and sacredness to native foods,” says Adán Medrano, a Mexican-American chef, food writer, and documentary filmmaker. “They give us a connection to our ancestors, and they make us cognizant of the seasons and of being nourished by Mother Earth.”

Historians believe Spanish colonists in northern Mexico were the first to actually plant pecan trees. By the mid-1800s, the first propagation using grafts was achieved in Louisiana by an enslaved gardener known only as Antoine. This marked “the beginning of modern pecan culture,” according to horticulturists L.J. Grauke and T.E. Thompson.

Today, hybridization is used to develop new nut varieties. Once a hybrid has been tested and demonstrates desired qualities, it can be grafted. Using flexible tape and wax, a twig or shoot from the desired hybrid can be attached to an existing tree, known as rootstock. Once the graft grows, all of the tree above the graft is the new desired variety.

The Aristocrat of Nuts

The Hill Country town of San Saba is home to a grand, towering tree known as the “mother pecan.” According to the Texas A&M Forest Service’s website, it’s “the source of more important varieties than any other pecan tree in the world … discovered by an Englishman named E.E. Risien who planted the first commercial pecan nursery in San Saba County.”

The greenhouse at Berdoll Pecan Farm grows young pecan trees

Risien founded the West Texas Pecan Nursery in 1888 and artificially pollinated the mother tree for years, using pollen gathered from male blossoms around the region. He also experimented with budding and grafting. Now, Risien’s great-great-grandson Winston Millican is a fifth-generation grower in San Saba. He farms more than 1,000 acres of pecans while his wife, Kristen Millican, oversees their store, Millican Pecan, which sells in-shell and shelled nuts, confections, pies, pecan butter, and roasted pecan syrup. The mother pecan still resides on their private property. Its health has been overseen by horticulturists who estimate its age to be up to 200 years.

Like the Millicans, the Berdoll family of Cedar Creek, outside Bastrop, has grown pecans for generations. Brothers Dan and Sebe Berdoll farm 100 acres purchased by their father in 1948. “Farming is hard work, and you don’t always earn a living,” Dan says. “It’s not a come in at 8 a.m., leave at 5 p.m. job, but it’s a good life. And I don’t have to commute. I step outside my door, I’m at work. I get off my tractor, I’m home.”

Dan’s niece, Jennifer Wammack, and her husband, Jared Wammack, own and operate Berdoll Pecan Candy & Gift Company, located in front of the farm off State Highway 71. Once you see Ms. Pearl, the world’s largest squirrel statue, you’ll know you’re there. In addition to their famous gooey pies, the Berdolls make fudge, pecan bars, brittle, honey butter, caramels, pralines, and chocolate clusters.

Next to the store, workers in the packing house process Berdoll pecans to be sold in-shell, whole, halved, or incorporated into confections and baked goods. During harvest season, the packing house resembles Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, as workers load hundreds of thousands of pecans into 14-foot hoppers. The pecans then topple onto conveyor belts to be sorted by hand, bagged, and shipped.

In sterile rooms surrounding the production area, employees variously dip, stir, whip, pour, bake, and package. The air is heady with the scent of chocolate, butter, and caramelized sugar.

Picking the Perfect Pecan

Pecans have a high oil content and degrade quickly if not stored properly. The nuts are best purchased fresh, in or out of the shell. Keep any leftover pecans you plan to use soon in a tightly sealed bag in the refrigerator. They will last up to two years in the freezer. The following are some of the most popular varieties grown in Texas.

Native: The pecan indigenous to Texas is small and slightly tannic, with an underlying buttery sweetness. It’s frequently used as a “topper” on confections or for oil and cooking.

Pawnee: Considered the bread and butter of the Texas pecan industry, this mellow-flavored nut is a good all-purpose choice and is particularly prized for baking due to its high oil content.

Choctaw: Large and sweet with a crunchy finish, these meaty nuts are excellent for baking and snacking, and as chopped garnishes.

Oconee: Coveted for its full flavor, large size, and overall quality, this Central Texas favorite is a good all-purpose pecan.

More Than Pie

The Berdolls grow six varieties of pecan, including the much-loved Pawnee, a large, rich, buttery nut with a pleasantly oily finish. In 1955, USDA principal horticulturist H.L. Crane proposed naming the new pecan varieties after the Pecan Belt’s Native American tribes, hence names like Comanche, Cheyenne, Choctaw, Oconee, Caddo, Nacono, and Lakota.

Jennifer and Jared Wammack (right), owners of Berdoll Pecan Candy & Gift Company, with Jennifer’s parents, Hal and Lisa Berdoll.

The variations in flavor and texture are appreciable, with some nuts having a substantial, meaty consistency; higher oil content; or more aromatic properties than others. These qualities are what determine their usage for baking, manufactured products (commercial confections, packaged pieces, oil), and snacking.

Texas Pecan Board executive director Whitney notes that, increasingly, chefs who prioritize regional sourcing are interested in purchasing specific varieties. “They like the idea of using something indigenous to Texas, but it’s also just that they taste really good and work well raw or cooked,” he says.

Michael Fojtasek, award-winning chef and owner of Austin’s Olamaie, which has garnered national acclaim for its contemporary Southern cuisine, frequently features pecans on his menus. “It’s always the first nut to come to mind,” says the native Texan. “I love cooking with them because they’re so versatile in how they can be presented, but they also have such dynamic flavor and texture. At the restaurant, I like to roast them very dark to get a deep, rich, tannic quality. At home, I love them candied with a fair amount of salt alongside a cold beer.”

In San Antonio, Steve McHugh, chef and owner of the restaurant Cured, has received similar accolades for his menu and commitment to the region’s farmers and ranchers. “I make an effort to incorporate ingredients that are indigenous to the region, from pecans to prickly pear,” he says. “There are so many varieties of pecan to choose from, and I love smoking them. Their oil holds the flavor really well, and we feature them in dishes like a kale salad or in sauces like a mole.”

Whether they’re Naconos or natives, pecan nuts and trees are intertwined with the story of Texas. For small growers like the Berdolls, Swifts, and Millicans, pecans are also a bridge between their community and America’s culinary and agrarian heritage.

“Knowing that we carry on a business that my parents started 40 years ago is a true blessing,” Kristen Millican says. “When we hear from the same customers every year for Thanksgiving pie orders, it gives us a real sense of pride in what we do.”

Shop Talk

There’s no pecan like a fresh pecan, and these farm stores have the goods, including pastries, confections, preserves, savory snacks, and bulk nuts. Purchasing directly from growers ensures your money goes to the local economy. Hours are subject to change due to COVID-19, as is availability of tours.

Berdoll Pecan Candy & Gift Company

Look for the world’s largest squirrel off State Highway 71 outside of Bastrop, and you’ll find dozens of sweet and savory treats, including the Berdoll family’s pecan pies, fudge, brittle, seasoned nuts, and in-shell and shelled pecans. All products are also available online. Tours available by appointment. 2626 SH 71, Cedar Creek. 800-518-3870; berdollpecanfarm.com

Millican Pecan Company

Decadent pecan butter, roasted pecan syrup, pies, “Caramillicans” (chocolate-caramel nut clusters), and nuts are all available in-store and online. Tours are by appointment and include the packing room and kitchen; farm tours are also available to groups. 199 CR 100, San Saba. 866-484-6358, millicanpecan.com

Swift River Pecans

Farmstead pecan oil, raw wildflower honey collected from hives in Swift’s orchards, in-shell and shelled pecans, handmade pecan wood cutting boards, lumber, and large wood slabs are all sold at the store and online. Tours by appointment. 9975 San Marcos Hwy., Lockhart. 512-212-0778; swiftriverpecans.com

Editor’s note: This story has been updated since its publication in our October issue to specify that pecans are the only major tree nut native to North America.