A

Notch

Above

The end of a 5-mile hike through McKittrick Canyon reveals the most beautiful spot in Texas

By Bobby Alemán

Photographs by Sean Fitzgerald

A hiker ascends to The Notch in Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

As we hike through desert scrub, the soft, light purple of a madrone tree catches my eye. Its boughs twist out with sculpted elegance. If I were to imagine a unicorn’s horn, the limb of a freshly peeled madrone would do the trick. The last time I was in Guadalupe Mountains National Park in West Texas, I was transfixed by the trees’ red bark. But I had forgotten they peel. That was summer; this is late fall. When the bark is new it is white and so smooth it gives the madrone another name: Lady’s Leg. In the spring, the trees bloom with white flowers, and in summer they begin to shed their bark. The glossy leaves carry clusters of red berries, sometimes called manzanitas. Their scientific name, Arbutus unedo, means “strawberry tree.” “This is a tropical plant!” exclaims our guide, Theresa Moore, the park’s acting superintendent and visitor services manager. A tropical plant in the desert.

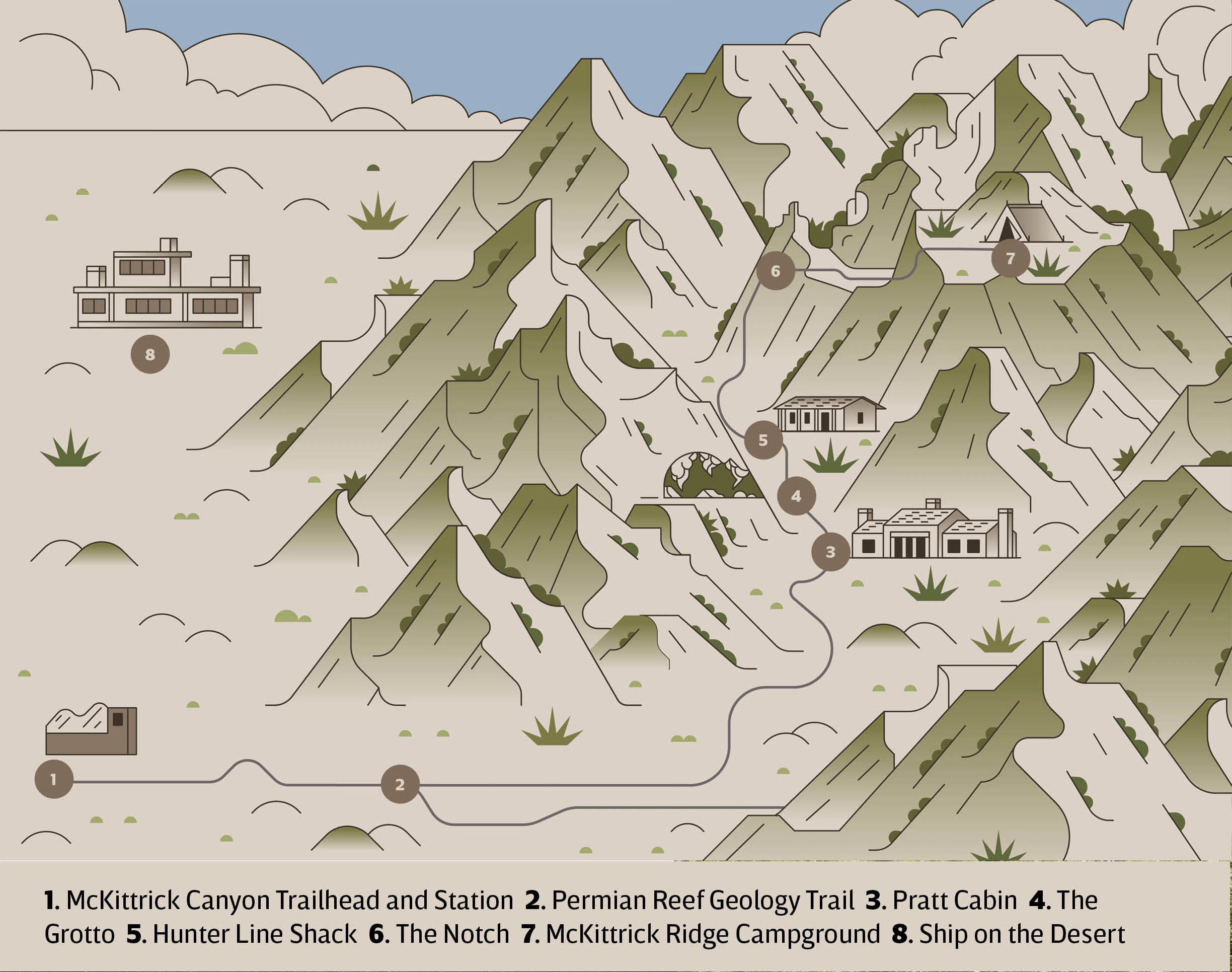

Illustration by Aldo Crusher

The Chihuahuan Desert surrounding us is a rarefied landscape. Hundreds of millions of years ago, the land was submerged in water. As the sea receded, the Guadalupe Mountains revealed themselves, along with various biomes that give the area its singularly rich biodiversity. From the desert floor to the high country, variations of sun and shade, moisture, and soils support wide varieties of plants and animals. Think of the terrain as a Venn diagram of “life zones,” where disparate environments coexist and where the Rocky Mountains, desert, and plains intersect at the limits of their ranges. Ponderosa pines and Douglas firs bend in the wind high above dunes, while pinkish madrones dot the background. All in one park.

According to the National Park Service, the madrone is a rainforest relict, a remnant species from a wetter climate following the melting of the Pleistocene ice cap. “The topography that you see, present day, reflects ancient environments, and there are very few places in the world where you can do that,” says Charles Kerans, a professor in the school of geosciences at the University of Texas.

The day before, my wife, Vanessa, and I drove nearly 500 miles from Austin to our yurt Airbnb overlooking the Guadalupe Mountains on a tractless plot in the desert. After unloading the car, I marveled at my surroundings. The entire mountain range refracted color: bars of seashell pink and blue that darkened with the sunset, turning a soft purple—just like a madrone—as the mountains behind me burned in gold and red. I had never been in a quieter place.

We are here to hike to McKittrick Canyon, a hidden wilderness in the park. Five miles in from the trailhead is a scenic view, a cleft on a ridge called The Notch, which uncovers a sweeping south canyon vista so picturesque that I proposed to Vanessa there five years ago. We’ve returned to see the leaves of bigtooth maples after they’ve changed color. Maples surrounded by desert. That’s just one of many paradoxes here. Chief among them is the unlikely story of Texas oilmen Wallace E. Pratt and the father-son duo of J.C. Hunter Jr. and Sr., who preserved McKittrick Canyon and helped establish the national park.

The writer’s base camp was a yurt in the desert. Photo by Bobby Alemán

A trail winds through the first “life zone” in McKittrick Canyon.

On the south end of the park, Pine Springs Canyon leads up to Guadalupe Peak, once called Signal Peak, the highest point in Texas. On top is a 6-foot-tall steel trylon memorial for air mail pilots, erected by American Airlines in 1958, the centennial of the Butterfield Overland Mail Company’s first completed route. A man named Noel Kincaid and a team of mules hauled cement bags and steel sections up the mountain when helicopter transport was ruled out due to high winds. They made over two dozen trips.

From the early 1940s to about 1970, Kincaid was the foreman of Guadalupe Mountain Ranch, a 72,000-acre spread owned by Hunter Jr., a petroleum engineer and independent oilman from Abilene. Kincaid lived at the headquarters, called Frijole Ranch, about a mile-and-a-half northeast of what is now the Pine Springs Campground. From here, in the early ’60s, he led Hunter Jr.’s guests on horseback for daylong promotional tours of the ranch, on the market then for $1.5 million. Hunter Jr. hoped to sell the land to the federal government for a future national park, but the government was averse to purchasing private land for parks with public funds.

Kincaid led groups, which included journalists and lawmakers, up Bear Canyon, then around a forested interior called The Bowl, and down into the oasis of McKittrick Canyon to a lodge called the Hunter Line Shack, located near McKittrick Creek. One congressman who made the trip in 1964 told the San Angelo Standard-Times, “I’ve never been on anything as scary as this in my life.”

A rock hammer door knocker adorns the Ship on the Desert

The Grotto is a prime resting spot

Fall color dots McKittrick Canyon

For us, with our feet on the ground, it’s not as frightening, but still no easy task. The McKittrick Canyon Trail is about a 10-mile round-trip march, with 1,092 feet of elevation change and hairy switchbacks at the end. Staying on course and carrying sufficient water to combat extreme temperatures—at least a gallon is recommended—are musts for a safe trip. This is part of Texas’ oldest and largest congressionally designated wilderness. That means no roads, no motorized equipment, no permanent buildings, and no cellphone towers. It means it’s wild. Only mountains, streams, trees, and quiet. As one park ranger tells me, “You feel like you’re alone every time you’re there.”

Moore, the superintendent, has made many attempts to guide family and friends to The Notch but tells me they never make it past Pratt Cabin, Pratt’s former vacation house. They sit on the porch, have conversations, and become so entranced by the environment that by the time they get up, it’s too late to continue to The Notch.

As we hike, Moore constantly stoops down to identify fossil rocks, like fusulinids. She tells us how the agave’s long stalk shoots up, growing inches a day to flower once, blooming with pods for bats it will dust with pollen before it dies. She also explains how more than a dozen nations have ties to the land in the park, notably the Mescalero Apache, or Ndé. This is their traditional homeland. “I would love for their story to be told,” she says.

We start our hike about a mile south of the state line with New Mexico, at the mouth of the canyon. This is the first life zone: the desert. The flower stalks of sotol blanket the area, sticking out of the ground like truffula trees from a Dr. Seuss book. Nothing hints at a change in landscape. But as we continue, on a trail of countless white rocks, the geological splendor of the landscape reveals itself once we round a bend. Mountains 7,000 feet tall are to our right and left. “But these aren’t really mountains—not in the traditional sense of mountains formed by squeezing, folding, and faulting,” says Dustin Sweet, a professor in the department of geosciences at Texas Tech University. They’re uplifts of an ancient basin floor. Indeed, the canyon wasn’t always like this. We are standing in what was once the coldest, deepest part of an inland sea.

If you look up to your right from the mouth of the canyon, a massive, golden cliff face made of rock that looks much different from the rest of the mountain sits at the top of the rim. This part is the Capitan Reef, once battered by waves of the Delaware Sea 260 million years ago—before dinosaurs. The strangest and most colorful marine creatures would have lived on that rock. The fossil reef is so stable, there is a connecting trail, the Permian Reef Trail, that winds its way up to the top.

The water at the top of the ridge would have been shallow, warm, and clear, with plenty of sun for algae to grow. The wall was slowly formed by animal and plant fossils, many of which were sponges that died on top of each other, cemented with secretions of lime by algae that held the structure together. Generations of these fossils formed the reef.

The base of the canyon is a watering hole for abundant wildlife.

“Reef is an interesting limestone in that it forms a rock as it’s essentially living,” Sweet says. “Some of these animals had hard parts, like a seashell. The seashell is the same mineralogy—calcium carbonate, or calcite—as makes up the rest of the rock. The seashell instantly becomes part of the rock.”

When the sea evaporated, sediment covered and buried the region. Later, the basin slowly uplifted, and 20 million years ago, sections of the Capitan Reef—much of it is still buried—rose several thousand feet. This is how we see it today.

Fossil remains that sank to the deep were buried and transformed into oil or fossil fuels. Oil pools are found underground in reservoirs where there were once ancient seas. A 2018 report by the United States Geological Survey assessed the “largest, continuous oil and gas resource potential ever discovered” in this greater region. That’s why in 1966 Humble Oil & Refining Co. drilled a roughly 7,000-foot stratigraphic test well, Pratt No. 1, here at the mouth of McKittrick Canyon. But they came up dry.

As we continue our hike, Moore spots a pile of orange rinds on the ground. She places them in a plastic bag and tells us we need to stop by Pratt Cabin to dispose of them. Once there, she gives us a tour inside the stone structure with a flagstone roof, green windowpanes, and a screen door. We sit on rocking chairs on the porch and talk. As I look out on the floodplain, sprinkled with alligator juniper trees bearing reptilian bark, I can see why previous travelers became transfixed and never made it any farther.

Theresa Moore leads the writer and his wife on The Notch trail.

In 1921, Pratt, a petroleum geologist from Kansas, visited Pecos on a scouting trip for possible oil leases in the region. He was accompanied by two brokers and a consultant named Judge Drane, a local attorney and bank representative. The latter approached Pratt with a proposal. If Pratt would supply the transportation and didn’t mind a bumpy ride, he would take him to see “the most beautiful spot in Texas.” Pratt agreed, and they ventured west on unpaved roads in a Ford Model T around 100 miles en route to McCombs Ranch, not far from the mouth of McKittrick Canyon.

“With me it was love at first sight,” Pratt said in a 1974 interview archived in the Southwest Collection at Texas Tech University. “Miniature lakes and miniature waterfalls” were everywhere. “Lush vegetation with many ferns covered the canyon walls right down to the water’s edge.”

The Ship on the Desert was a modern home built on the east slope of the Guadalupe Mountains in the 1940s.

Pratt purchased the McCombs property after learning Green McCombs, a cattle rancher, had gone bankrupt. He later named his new ranch Madroñal Ranch, after the madrone. But Pratt wasn’t the only one buying up property in the Guadalupe Mountains. His new neighbor, Hunter Sr., was acquiring land as well. Once a teacher in a one-room school in Van Horn, Hunter Sr. later became county treasurer, a judge, and a banker. In 1926, like so many others, he joined the oil boom and began handling oil leases in the Permian Basin. Driven by the Great Depression, he bought several ranches—many foreclosures—according to Dr. Jeffrey Shepherd, author of Guadalupe Mountains National Park: An Environmental History of the Southwest Borderlands. Hunter Sr.’s combined acquisitions became Guadalupe Mountain Ranch, virgin land except for pasture accommodating upward of 3,500 Angora goats.

But what Hunter Sr. wanted to do with his property was quite unusual for the time—especially for an oilman. He campaigned for his ranch to become a park. Hunter Jr. told the San Angelo Standard-Times in 1965 that his father had always been interested in parks and was one of the first who lobbied for the creation of Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico, even taking some “federal dignitaries into the caverns in the old iron bucket.”

In the early 1930s, Pratt built his eponymous cabin in North McKittrick Canyon. Just across the creek, Hunter Sr. was still hosting picnics and parties in the heart of South McKittrick, trying to get government officials to bite on his proposal. A couple years later, Roger W. Toll, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, visited Texas, scouting for possible park locations for the National Park Service. Hunter Sr. offered his 43,200 acres for $237,600, equivalent to about $5.4 million today. But Toll passed on the Guadalupes, in part because acquisition policies at the time were unfavorable.

Know Before You Go

Where to gas up: Dell Valley Oil is a combination auto parts store, curio shop, and gas station with old-time pumps that roll back like slot machines. 7 a.m.-6 p.m. most days, closed Sundays. 109 E. Broadway St., Dell City. 915-964-2875

Where to grab essentials: Load up on groceries, ice, and highly recommended tacos—plus burritos, hamburgers, and guisos—at Two T’s Grocery Store. 201 W. First St.,

Dell City. 915-964-2319

Where to stay: If Pine Springs Campground at the park is full (recreation.gov), try the yurts and campsites at More Travel Less Talk via Airbnb (moretravellesstalk.com). There, enjoy matchless views of the sunset and western ridge of the Guadalupes outside Dell City, 27 miles from the park.

“They had financial limitations on what they could turn their attention to,” explains Monte Monroe, the Southwest Collection archivist at Texas Tech University and official Texas state historian. “They were looking for the biggest bang for their buck, the most monumental bang for their buck. The most beautiful, the most scenic. And the easiest to acquire.”

By 1937, Pratt had become an executive with Standard Oil Co. (now Exxon), in New York, and lived in a flat overlooking Central Park. His wife, Iris Calderhead, a suffragette who had been jailed briefly for picketing outside the White House for women’s rights, vacationed with her husband at Pratt Cabin. But due to a flood that “imprisoned” them there for a week, they decided to build a new home just outside the eastern front, in Lamar Canyon. The sleek, modernist house, designed by New York architecture firm Milliken & Bevin, featured a two-car garage and an airstrip for Pratt’s Fairchild 24, a three-seat passenger plane he piloted himself.

They had an unusual name for their new home: Ship on the Desert. They moved there in 1945, the year Hunter Sr. died, and stayed for 15 years, without telephone, TV, or radio—or any doctor nearby. “We loved it,” said Pratt in a 1972 taped interview archived at the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum in Midland. But time caught up with them. “We suddenly got old.”

Pratt had been flying Calderhead back and forth to Tucson, Arizona, for the treatment of her arthritis. But likely due to cataracts, he stopped flying. According to Jim Adams, a pen pal of Pratt’s, Pratt offered Madroñal Ranch to his son, who declined. This set in motion his donation of 5,632 acres to the National Park Service, which launched the acquisition of the 72,000-acre Guadalupe Mountain Ranch, owned by Hunter Jr. Led by the tireless energy of Hunter Jr.’s realtor, Glenn Biggs, the ranch finally sold. This was the first time private land was purchased for a park with government funds. Guadalupe Mountains National Park opened Oct. 6, 1972.

When Calderhead died in 1966 and Pratt in 1981, their ashes were spread in McKittrick Canyon.

The downward view from The Notch is “the most beautiful spot in Texas.”

After our stop at the cabin, we press on for The Notch. We cross McKittrick Creek and listen to the water purl around rocks. First a tropical plant in the desert, now a spring-fed, perennial stream. I step onto a boulder to look down the bend and then turn around and look up the trail. There they are: two stands of bigtooth maples, like an unexpected explosion of confetti.

I’m mesmerized by the red and orange foliage. Maybe it’s because we’ve been in the desert for miles. Or maybe this sudden change and vivid transformation of leaves is just normal in a true wilderness—the second life zone.

“You get one impression of it as being this hardscrabble type of place,” says Michael Haynie, a 25-year veteran park ranger, “and then you hike into a lush, riparian woodland, and it’s just—transformative.”

Moore spots a ponderosa pine, jogs up to it, and wraps her arms around the trunk. She inhales deeply and turns around with excitement, inviting us over. “When the sun hits the bark and you smell it,” she says, inhaling again, “women smell vanilla. Men, usually caramel.” It’s so intoxicating I’m tempted to take a bite.

A hiker rests at The Notch

We are surrounded by mountains. They appear split in two by the canyon. This is no longer reef but bedded limestone, marked by drip stains of calcium carbonate from water running down its walls.

We encounter a marker for The Grotto—a shaded grove at a lower elevation. This is easily the biggest temptation to stop and explore on the way to The Notch. Below, hikers will find stands of yellow maples by the creek, stone picnic tables, and a small cave with stalagmites and stalactites providing shade and a resting place. It stays cool here no matter how hot it gets. The Hunter Line Shack, a space where the Hunters entertained guests, resides here.

We soldier on, entering a break in the trees. The sun is out, unimpeded. We are approaching the final life zone: the mountain zone. Wooded slopes are flecked with the maples’ fall colors amid the dark greens of ponderosa pines, sotol, and agave. Lady’s Legs reveal their light pink and purple bark here and there. Two-thousand-foot canyon walls swaddle us. I hear McKittrick Creek flowing below.

High on the transverse ridge in front of us, we eye The Notch. Two rock formations that look like turtles come into focus on the horizon. Below the smaller one is a gap in the rock—a window to “the most beautiful spot in Texas.”

Vanessa and I look at each other and plunge ahead. We have maybe a quarter-mile to go. After we pass a dynamited stairway, I look back at the canyon bowl and the brick-red line of trees along the creek, wiping the sweat off my face. I let Vanessa go ahead so I can see her reaction when she makes it to the top. She approaches slowly, then comes to a complete stop and plants her sticks into the ground.

Madrones growing from each side of the rock guard the view. We step behind them, inhale, and take in the lush sight of South McKittrick Canyon. The mountains domino behind each other and McKittrick Creek meanders along the base, where mountain lions and black bears are known to drink. We’ve made it. The hike is only half over, but the day is complete.

The following evening, we meet Moore on McKittrick Canyon Road. We drive to the Ship on the Desert and walk through the purple front door with a rock hammer door knocker, then up the spiral staircase to the roof deck. Purple, the color of the suffragist, and the hammer, a geologist’s tool. I think we count 12 shooting stars. We discuss the house with Moore and the ways it could be accessed by the public, after its restoration is complete.

I notice lights visible on the horizon.

“I didn’t know you could see Carlsbad from here,” I say. Moore smiles and says, “Oh, that’s not Carlsbad. That’s the Permian Basin.” Numerous illuminated oil fields. Another paradox.

Oil was the family business for Pratt and the Hunters, too, but they decided to strike it rich another way: preserving the most beautiful spot in Texas.