The wild

of Texas

Lessons for living alongside

the venomous and non-venomous predators

in an ever-growing state

Look at her. So poised. So regal.

Watching her gracefully slither through my yard hunting for her next meal this sultry summer evening, I make sure to say hello before chopping her head off with my hoe. That’s been my attitude toward the gorgeous, copper-toned serpents that surround my lakeside home in North Texas.

But Chuck Swatske is trying to convince me to retire my hoe. Swatske, certified a master naturalist by Texas Parks and Wildlife, wants to educate me about the ecological benefits of copperheads and other Texas snakes. They devour mice and rats, helping to curb the disease-carrying rodents from running rampant in urbanized areas, he notes. Wild snakes are also an important food source for birds of prey like owls, hawks, herons, and roadrunners. Not to mention, toxins drawn from venomous snakes have been developed to treat medical conditions such as heart disease and arthritis.

That’s why I’m sheepishly “herping” with Swatske across a trail that winds alongside a dry chaparral-covered creek bed. We’re out to capture a bunch of copperheads and other venomous serpents before they encroach on the well-manicured lawns bordering the Lantana Golf Club or the rows of pricey houses popping up inside wrought-iron fences lining Copper Canyon, about 30 miles north of Dallas-Fort Worth. It used to be “Copperhead Canyon,” by the way, originally named by Texas pioneers who encountered swarms of snakes as they built their small settlement atop the area’s rolling hills and rocky canyons.

Swatske knows if a homeowner encounters a copperhead in their yard, they’ll likely chop its head off with a shovel, an ax, a hoe, or any other handy weapon. By rounding up the copperheads and relocating them away from urban neighborhoods, Swatske says, the serpents and the homeowners are better off. In the last 12 months, Swatske, a retired semiconductor salesman, has captured and relocated about 100 copperheads crawling around these parts.

Snakes 101

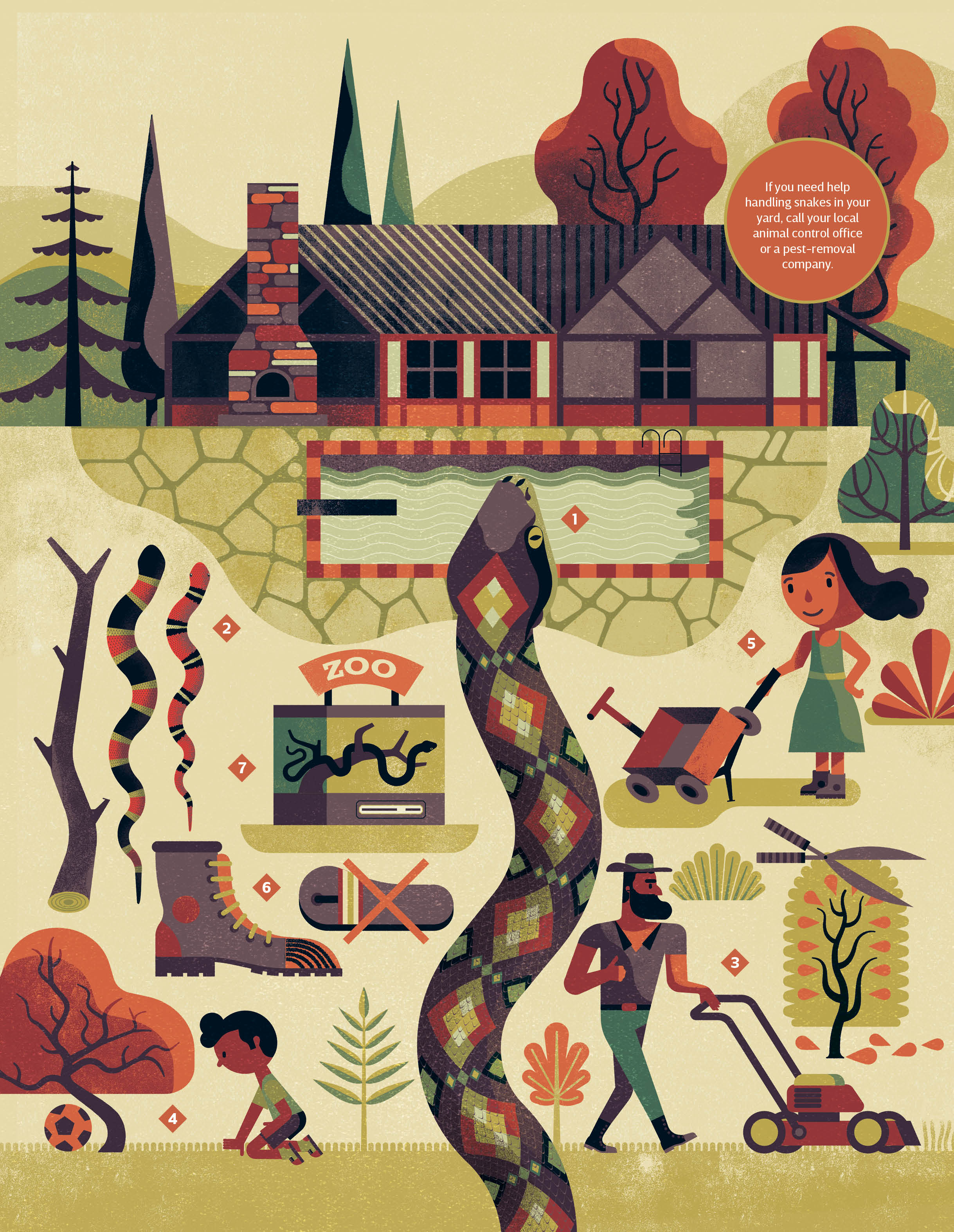

Be aware that venomous snakes can be close by even though you don’t see them. Snakes are just about everywhere in Texas.

1A harmless rat snake is often mistaken for a dangerous rattlesnake, especially when it feels threatened and starts beating its tail against some sticks to make you think it’s a rattler. Similarly, several species of harmless water snakes are frequently mistaken for venomous water moccasins. One of the ways to tell the difference is to watch their behavior. Water snakes like to hang together around marinas, boat docks, and populated lakes, swimming with their heads above the surface and their bodies below it. Water moccasins typically swim alone and often below the surface of the water, hunting for fish to eat. If you encounter one, it will likely try to scare you away by coiling up, thrashing its tail like a rattler, and displaying its fangs. If the inside of its mouth looks like a ball of cotton, you’ll know it’s a water moccasin (aka cottonmouth). If in doubt about a snake, the best way to avoid getting bit is to leave it alone, even in your yard. Eventually it will slither back into the wild.

2The harmless Mexican milk snake or the scarlet king snake are easy to spot in your yard with their brilliant bands of red, yellow, and black. To distinguish the milk snake and king snake from the coral snake, the classic rhyme holds true in most cases north of the border: “Red on yellow, kill a fellow; red on black, venom lack.”

3Mow your grass low to the ground and trim your bushes and flower gardens back so you can see what’s underneath them.

4If your 5-year-old kicks her soccer ball into the bushes, make sure she gets down on her hands and knees to check for snakes before she reaches for it.

5As soon as your children are old enough to walk, take them into the yard, put a long stick in their hands, and teach them to poke underneath objects before they pick them up with their hands.

6Wear flip-flops and sandals with caution. Sturdy hiking boots have saved many suburbanites from bites.

7Visit the reptile exhibit at your local zoo to show your children what pit vipers and coral snakes look like.

Wearing a shirt proclaiming “SNAKE LIVES MATTER,” Swatske sounds like an evangelical preacher talking about respecting and protecting snakes, even venomous ones, to anyone who will listen: Boy Scout groups, garden clubs, local chapters of master naturalists, and neighborhood social media forums where panic-stricken homeowners dispense advice on how to drive away snakes. Remedies these days include mothballs, glue traps, pesticide sprays, ultrasonic sound machines, chickens, and feral cats. “None of them work,” Swatske says.

Swatske acknowledges that persuading Texans not to stamp out snakes, especially those with children and dogs, is a hard sell. Most Texans fear snakes and can’t tell the difference between the dangerous and the harmless ones. “In their minds, the only good snake is a dead snake,” he says. “And I really can’t blame them. Copperheads, cottonmouths, and other venomous snakes can be dangerous, even deadly.”

Swatske gets no argument from me. One particularly dreamy weekend at Lake Grapevine, my wife, Cindy, and I enjoyed sunbathing on our dock, water-skiing, and watching a Friday evening fireworks display. About 9:30 p.m., we hauled our boat out of the water and pulled it into our driveway to scrub off some smelly algae.

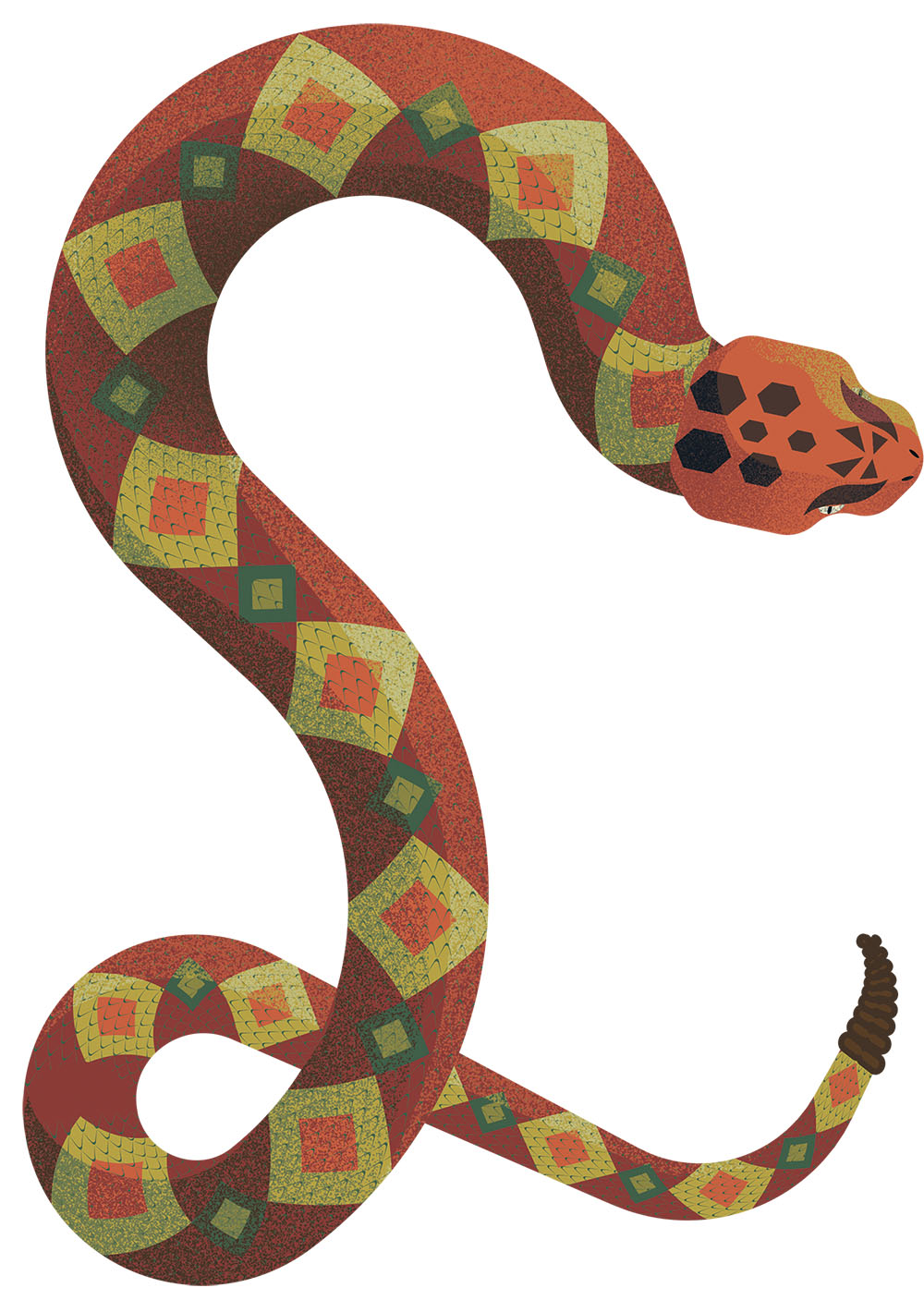

Southern copperhead. Photo: Derrick Hamrick/Rolf Nussbaumer

As I stepped across the hose to turn off the faucet, the copperhead struck. I had imagined what it might feel like ever since my 17-year-old son was bitten five years earlier in our backyard. But it wasn’t until that evening—July 17, 2012—that I realized I had sugar-coated the memory to tolerate living among our thriving copperhead population. The bite burned as if the snake had held its mouth over red-hot coals and then driven the molten fangs into the top of my ankle. The memory of those teeth slicing through my skin will remain with me until the day I die.

Like other suburbanites who get bit in their lawns or flower gardens, I was certain I was going to die that night. “Most people who get bit by a copperhead think, ‘I don’t have a chance of surviving this thing—I’m dead,’” says Jonathan Campbell, a herpetologist who recently retired from the University of Texas at Arlington. “Chances are you’re not going to die. But you’re probably going to suffer a lot.”

As houses, schools, and shopping centers spread across snakes’ natural habitat, unsuspecting people like me increasingly fall victim to venomous snakes. Surprisingly, travelers to some of the most remote regions of West Texas are less likely to get bit by a venomous snake than suburban dwellers. In Big Bend National Park, where 450,000 visitors flock each year, park officials report just two snakebites in the last eight years, neither of them fatal. In the rugged Guadalupe Mountains National Park, which draws 200,000 tourists a year, no one has been bitten by a snake since the park opened in 1972. “The mindset among hikers out here is they know they are in the wilderness and they know there’s dangerous snakes, and so they carry sticks and flashlights and they’re always on the lookout for them,” says Michael Haynie, a park ranger in the Guadalupe Mountains. “But when they get home they go into autopilot and don’t pay attention to their surroundings. That’s when they get bit by a snake nesting next to their pool.”

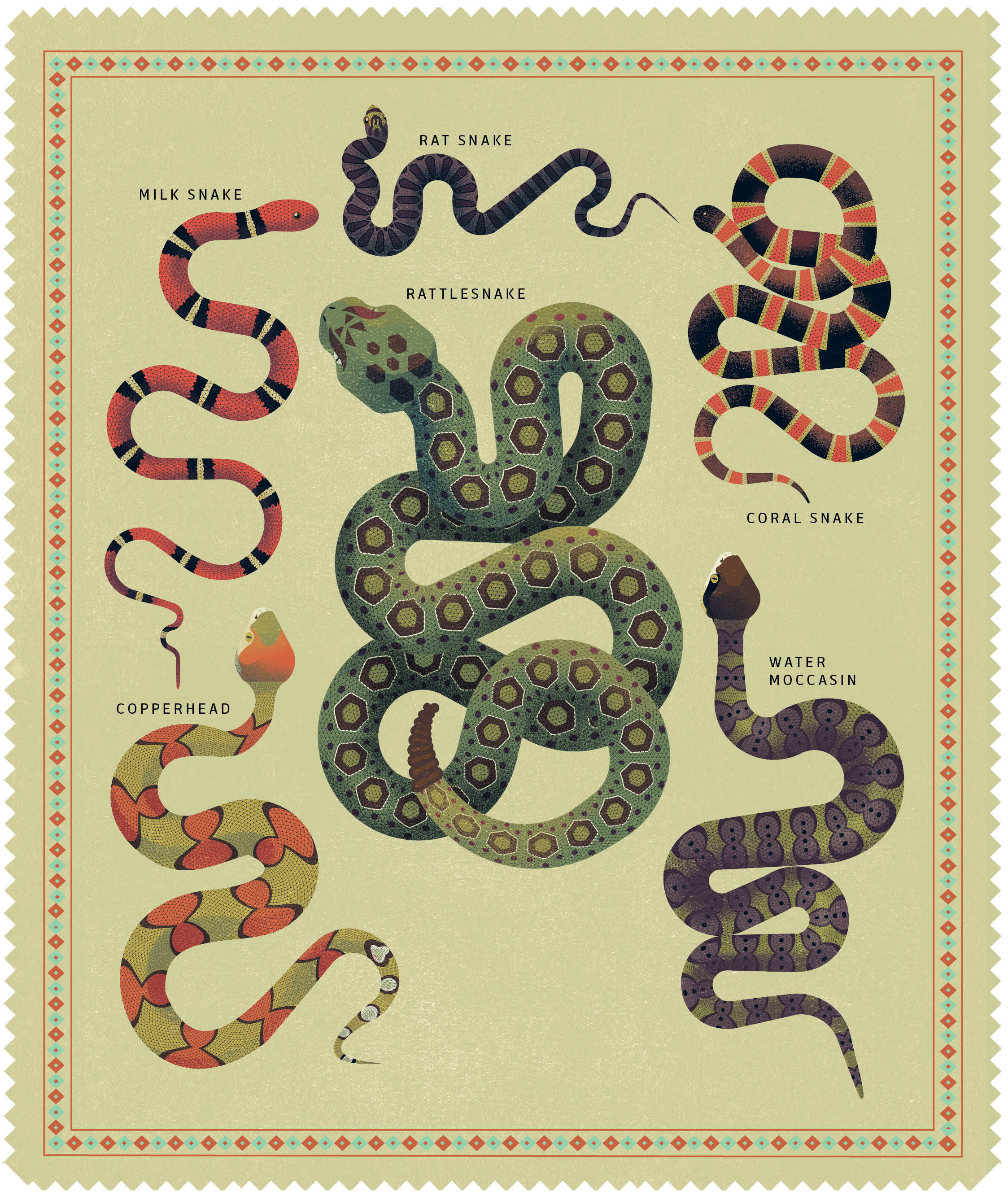

Know your snakes

Texas is home to four venomous snakes: copperheads, rattlesnakes, water moccasins (aka cottonmouths), and coral snakes. Harmless milk snakes, sometimes mistaken for coral snakes, are easy to spot with their brilliant bands of red, black, and yellow. Non-venomous rat snakes are widespread in Texas, pose no threat, and are good rodent predators.

![]()

Is that snake in your yard dangerous?

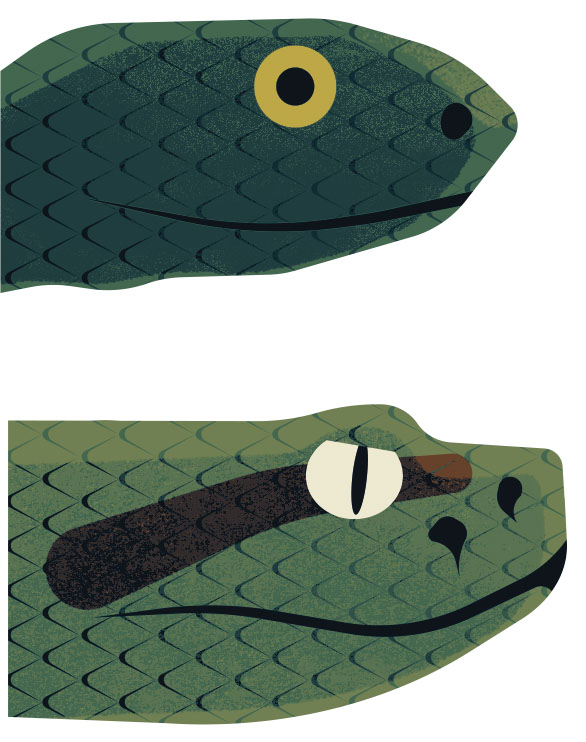

Top: Not a pit viper // Bottom: Pit viper

Rattlesnakes, copperheads, and water moccasins all belong to the same family of pit vipers. The best way to distinguish these deadly snakes from the many harmless varieties in Texas is to look at their eyes—from a safe distance. If they have elliptical eyes like cats, with small pits under their nostrils, they’re pit vipers.

![]()

Texas has four highly dangerous snakes: copperheads, rattlesnakes, water moccasins (aka cottonmouths), and corals. Last year, 1,352 venomous bites were reported to poison centers in Texas, up 33% from five years earlier.

But many venomous snakebites aren’t reported, meaning the number may be significantly higher. At Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Flower Mound, for example, Dr. Sean Fleming, medical director of Emergency Services, estimates he and his emergency room physicians call the North Texas Poison Center in only one out of 10 snakebite cases—if, for example, the patient is having a severe allergic reaction to the antivenom, which is rare.

Copperheads, rattlesnakes, and water moccasins belong to a family of venomous serpents called “pit vipers” for their infrared sensing pit. The organ between the eye and nostril acts like a heat-seeking missile, enabling a pit viper to detect and strike its prey with uncanny speed and precision. Pit vipers have long, movable fangs in their upper jaw that fold back until they’re ready to strike. As the snake opens its mouth, the fangs swing forward at a 90-degree angle and, in a stabbing motion, inject venom into its prey. The fangs of the coral snake, the only dangerously venomous snake in Texas that’s not a pit viper, are short and immobile. But their venom is extremely toxic, sometimes causing respiratory paralysis and death.

People encounter snakes everywhere: in parking lots and playgrounds; coiled under car hoods and gas pumps; swimming in backyard pools; slung around barbecue smokers and wooden fences; and sunning on the front steps of restaurants and churches. Any of the thousands of visitors stopping along highways to snap scenic shots of bluebonnets blooming in the spring shouldn’t be surprised to see a wild snake or two slinking through the flowers.

One of the main reasons wild snakes love urban environments is the abundant supply of their favorite food: rodents. Cities produce lots of garbage. Garbage attracts lots of mice and rats. And mice and rats attract snakes. “Snakes are one of the most effective means of rodent control in urban areas,” says Stan Mays, curator of herpetology at the Houston Zoo.

On Galveston Island, an hour’s drive southeast of Houston, miles of sand dunes covered with drought-resistant vegetation offer ideal habitat for rabbits and rodents. Western diamondbacks nest among their prey and seldom venture outside—except during spring and summer. Just as college students arrive for spring break, the rattlers slink sensuously from the dunes to frolic along the sandy shores. A few scattered signs near wooden walkways crossing over the dunes warn visitors about the rattlesnakes. But high school and college kids don’t always read signs.

That was the case with Austin Fleming, a 16-year-old from Galveston. During prom weekend in May 2018, he and some friends rented a house on Jamaica Beach. Around 11 p.m., the teens decided to stroll along the beach. As they crossed a wooden bridge over the dunes, Austin felt “something” bite him on his left ankle. He rolled up his black jeans, saw two bloody fang marks, and heard a rattle. Seeing a Western diamondback slither like a wave across the sand in front of him struck him as utterly surreal. “It never would have occurred to me that there were rattlesnakes on the beach,” he recalls.

A diamondback rattlesnake. Photo: Rolf Nussbaumer

Austin doesn’t remember how he got to the hospital. But he’ll never forget the ghastly sight of his swollen leg propped up on a pile of pillows. It was distended and discolored—purple, green, and every shade of gray. “It looked like a dead fish.”

Despite early infusions of antivenom, Austin began having chest pains, trouble breathing, and decreased blood flow in his leg, building pressure in his muscle tissue to dangerous levels. His doctors considered performing a limb-saving series of incisions called a fasciotomy to relieve the pressure. “That alarmed me,” says Yesenia Sandino, Austin’s mother and a neonatal nurse at the same hospital.

A co-worker reached out to Dr. Spencer Greene, a renowned toxicologist in Houston who specializes in treating snakebites. Greene called Yesenia, urging her to push her son’s physicians to resume Austin’s antivenom treatments even though he suffered nausea and diarrhea from the initial infusions. Austin’s doctors obliged his mother. During his 10 days in the hospital, they administered 18 vials of CroFab, an aggressive antivenom regimen that Yesenia believes saved her son’s leg and his life.

Austin was one of 970 rattlesnake-bite victims in Texas—and 5,781 nationwide—reported to poison control centers between 2012 and 2018. Eleven of those people—none in Texas—died, some before they even made it to the hospital. When a rattler bites, its venom destroys muscle and organ tissue that can lead to internal hemorrhaging, shortness of breath, and in rare cases, heart failure and death. Small wonder then that in the minds of many Texans, rattlesnakes are vicious predators.

ouch! That Snake Bit Me.

what do i do?

The recommended first aid and medical treatment for snakebites is still a confusing mishmash. “There’s an awful lot of bad advice out there,” says Dr. Spencer Greene, a Houston toxicologist who has treated more than 700 snakebite victims. If you get bit, Greene recommends the following steps:

Remove constrictive clothing and jewelry.

Don’t cut and suck or use commercial suction devices. “They don’t remove venom,” Greene says. “They just suck.”

For copperhead and cottonmouth bites, place the bitten extremity above heart level. If it’s a rattlesnake bite, keep it at heart level.

Don’t apply heat or cold.

Don’t apply a tourniquet.

If it’s a pit viper bite, don’t use constrictive bandaging. But if it’s a coral snake, pressure immobilization may help limit absorption of its neurotoxins into the bloodstream.

Before driving to the closest hospital, call ahead to make sure it stocks antivenom and that the emergency room staff has experience in snakebite treatment. Most don’t.

Do not bring the snake—dead or alive—into the hospital. “Even a dead snake can still envenomate you,” Greene says.

![]()

Copperheads, unlike rattlesnakes, have a reputation as a relatively benign pit viper. Many emergency room doctors still believe a copperhead’s venom isn’t very potent. Of the 2,671 copperhead bites reported in Texas between 2012 and 2018, none were fatal (although in that time frame, two victims died elsewhere in the U.S.). No deaths resulted from the 324 water moccasin bites in Texas during the same period. Nevertheless, Greene, the Houston toxicologist, says emergency room physicians should take copperhead bites more seriously. “Copperhead bites have the potential to create serious morbidity and, on occasion, mortality issues,” he says.

I can identify with Greene’s frustration. Last October, my wife was walking near our mailbox when a tiny, yellow-tailed copperhead bit her. With ice covering her swelling ankle, I drove her to a Grapevine hospital. The emergency room physician immediately offered to give Cindy antivenom “if we wanted her to.” But the physician warned us the antivenom could cost more than $50,000, and she wasn’t sure it would help. My wife wasn’t treated with antivenom and still suffers muscle and nerve damage from the bite.

Like me, most people who move into the sprawling suburbs around Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, Austin, Lubbock, and other metropolitan areas are oblivious to the venomous snakes living in the region long before they arrived—until they encounter one.

Travis and Marcey Cantrell live in a beautiful brick house near a picturesque creek, about a mile away from my home. A few months ago, Travis was preparing to grill chicken as his children bounced on the backyard trampoline. When he reached for a twig, a copperhead coiled underneath the wooden fence struck its fangs deep into the tip of Travis’ index finger. He screamed in pain and tumbled over backward.

Photos taken in a local hospital show Travis’ index finger, bloody and mangled, sprouting a bulbous black blister. Six hours later, the pain had spread up his elbow to his shoulder, and his doctors decided Travis needed three infusions of antivenom. The serpent’s fangs left a hole in his finger tip, but the injury did not require surgery.

The Cantrells now live in constant fear for their children’s safety. When they moved into their home four years ago, the couple didn’t think twice about walking barefoot to the pool or the trampoline. Now the kids don’t walk outside alone, and certainly not barefoot. The Cantrells also have to worry about visitors. Recently, guests faced an unidentified snake slithering outside the Cantrells’ front door as they were leaving. Travis grabbed a shovel and chased the serpent around the bushes, determined to kill it before it bit someone.

But the snake slipped away. A day later, Swatske, the snake relocator, was called in to catch the snake. I went with him. With headlamps mounted on our caps, tongs and buckets in hand, we prodded shrubbery with our tongs and walked along the fence until we spotted the serpent next to the trampoline—exactly where a copperhead had bit Travis six weeks earlier.

As Swatske moved in quickly with his tongs and slid the snake into his bucket, I realized this would be the first time I had shined my light on a copperhead not to kill it, but to save it.

The next day, we drove 15 miles from my home to a wilderness expanse on the west end of Lake Grapevine. No civilization was within sight. As two giant blue herons flapped overhead, I gently picked the copperhead out of Swatske’s bucket and set it down on a dead tree limb straddling Denton Creek. Suddenly I felt my hatred toward the wild serpents that have terrorized my family for years evaporate. In giving the copperhead back to Mother Nature, I sensed the snake and Mother Nature were freeing me from the tyranny of fear and loathing I harbored for snakes. For the first time in 30 years of living among the snakes, I felt a sense of serenity—even joy—about doing my part to get along with my wild neighbors.