The shallow pool at Pecan Springs Karst Preserve provides a magical setting. Photo by Rich Kostecke.

“To the bat cave!” Rachael Lindsey says with a grin. We’re standing at the base of a giant cottonwood near a spring-fed stream in northern Williamson County, about an hour north of Austin. Sycamores arch over the water, their leaves rustling in the hint of a breeze, and a cardinal sings out from behind us. No one wants to leave, but the bat cave is the last stop on today’s tour, and speleological curiosity prevails. We jump back in Lindsey’s SUV.

As we drive, Lindsey, the director of science and stewardship at the Hill Country Conservancy, points out other highlights of the new Pecan Springs Karst Preserve. Another journalist and I have accompanied her and Rich Kostecke, the conservation and science specialist at the conservancy, on a preview of the new preserve before it opens to the public for guided tours. An anonymous landowner recently donated the 1,205-acre spread to the conservancy, along with $1 million to help the nonprofit take care of it.

Tucked between Florence and Jarrell on a one-lane county road, the property contains dozens of sensitive ecological features including springs, caves, a wetland, and a mature juniper forest where the endangered golden-cheeked warbler nests. Unlike a park, which prioritizes human use, the emphasis at a preserve is “the ecological function and the species that use that area,” Lindsey explains. The conservancy will focus on research and restoration of the land, but the public also will have access via guided tours of the springs and cave offered every few months.

A karst landscape is one created through the dissolution of rock—in the case of Central Texas, the rock is porous limestone that water eats away over millennia to form caves and sinkholes. Rain filters down to the aquifer and returns to the surface via seeps and springs. Endangered salamanders live underground, sometimes visiting the surface in the springs. In a karst landscape, the worlds above and below ground are constantly in dialogue.

Our first stop this morning was Pecan Springs, one of three springs on the property that have continued to flow even during this year’s unrelenting drought. Decades ago, a previous landowner boxed in the springs with a rock wall and small dam, creating a shallow pool to serve the nearby homestead and provide drinking water for livestock. The human intervention slowed the spring’s downstream flow, and in a dry year like this one, the 18 inches of water in the pool are bordering on stagnant.

But it’s still a magical setting in the golden morning light. The branches of an enormous bur oak stretch over the pool. Dragonflies dart around the edges, and water bugs ski across the surface. Beyond the dam, Pecan Springs Branch creek burbles quietly through the former cow pasture.

The Salado salamander, a threatened species found in fewer than a dozen locations between Georgetown and Salado, lives in or beneath the pool. No one has seen a salamander here yet, but biologists from The University of Texas at Austin have detected their presence with a technology that identifies DNA present in water samples. Right now, Lindsey explains, the salamanders are probably staying underground because the pool doesn’t have enough spring flow or plants for them to hide under to escape predators like mosquitofish and crayfish.

The conservancy plans to remove the rock wall and dam and restore the eroded stream banks to return Pecan Springs Branch to a more natural flow. That’s likely to create conditions that coax salamanders through the spring opening to the surface.

The salamander DNA is a hopeful sign, Kostecke says. “It suggests to us that if we do the restoration—if we create the surface habitat—we’re likely to get a really positive response from the salamanders pretty quickly, because they are somewhere right underneath there.”

We hear a snort behind us, and a couple dozen yards away a feral hog with a passel of piglets trots by, indifferent to our presence. Lindsey has seen turkeys, white-tailed deer, foxes, and bobcats here, too. As we return to the car, she nearly steps on a rough green snake. We stop, and it stops, and humans and snake stare at one another for a moment before it slithers away.

On the other side of the property, we get a glimpse of what Pecan Springs could become after restoration. A yet-unnamed spring emerges from an opening in the rocks, silently spilling across a wetland the size of a suburban backyard. Sycamore, pecan, and walnut trees tower over the wetland, and frostweed and milkweed cluster at its edges. The round leaves of deep-green watercress fill the cold, shallow water.

Here, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists have conducted old-school salamander surveys, literally picking up rocks and looking under them for the elusive amphibians. They measure them and take a tiny tail clipping—salamanders can regrow their tails—to get a DNA sample before releasing them. Lindsey and Kostecke start their own quick survey, and after a minute Kostecke finds a salamander. It’s a few inches long, semitranslucent, and pinkish brown, with tiny, stumpy legs and a long tail. After a moment it darts back under the watercress leaves.

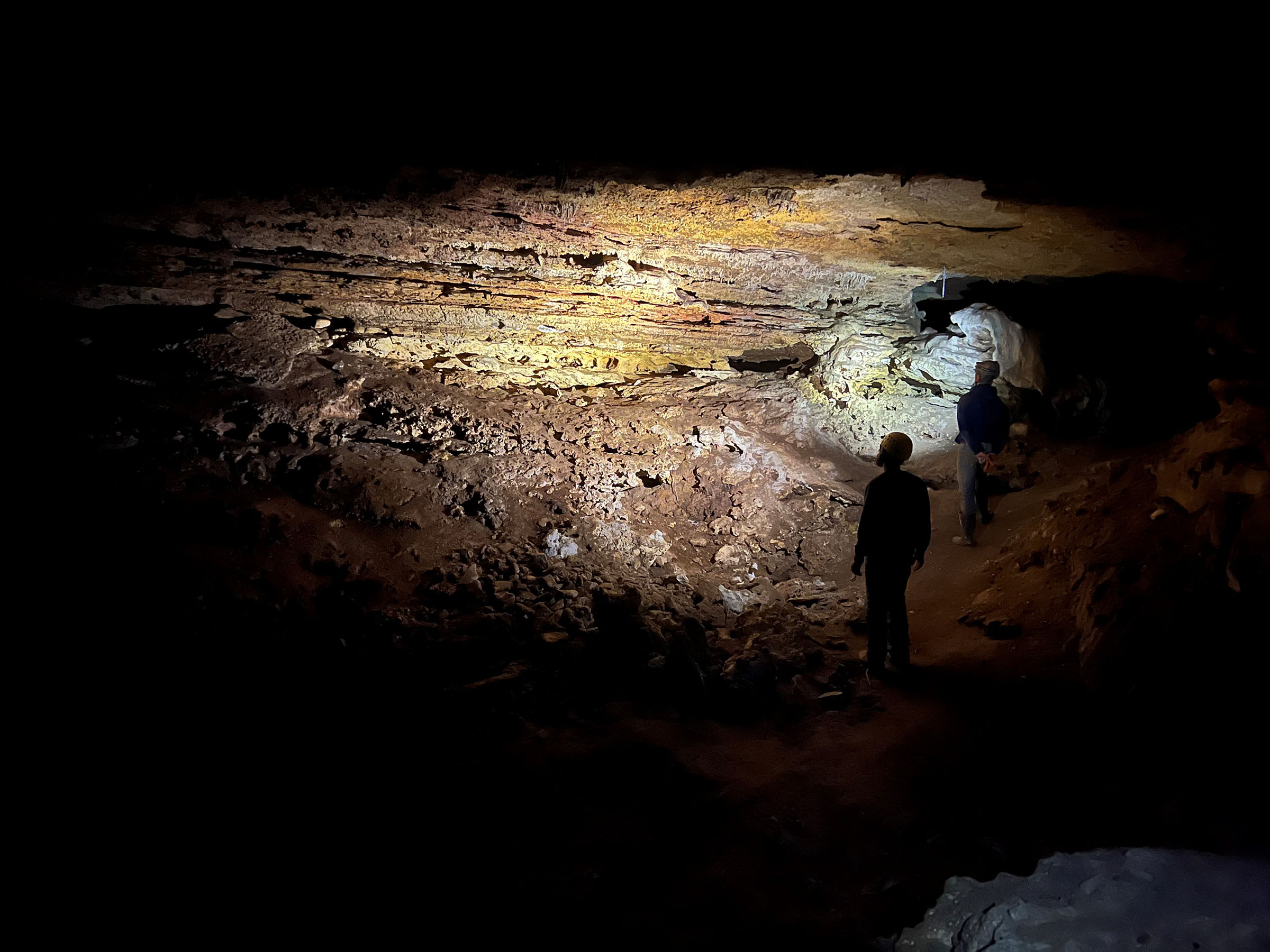

The largest cave at Pecan Springs Karst Preserve is home to bats, daddy longlegs, and other animals. Photo by Rachael Lindsey.

Visit a Preserve

Preserves across the state welcome visitors on designated days. Check to see if reservations are required and whether dogs are allowed.

West Texas: The Nature Conservancy’s Davis Mountains Preserve opens for hiking and camping four weekends a year, including Oct. 20-22.

Piney Woods: The Texas Land Conservancy’s Ivy Payne Preserve near Palestine offers guided and self-guided hikes and camping two weekends a year, including Nov. 17-19.

Southeast Texas: The Nature Conservancy’s Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary near Silsbee is open to the public every day for hiking, birding and paddling.

At last we head to the bat cave, the largest of six known caves on the property. Dry grass crunches beneath our shoes as we walk through a persimmon grove to the sinkhole at the entrance. The sinkhole once was part of the cave, Lindsey explains, but water dissolved the ceiling until the roof collapsed. We climb down the limestone rubble until we’re standing beneath a grotto-like overhang, peering into the darkness. As we step inside, the temperature cools by 10 degrees. Lindsey’s headlamp illuminates cave crickets and thousands of harvestmen—or daddy longlegs—wiggling in shaggy clumps overhead. Short stalactites called “soda straws” dangle from the roof like pointing fingers. The fingertips glisten with a drop of water, and we hold our breath and listen for an intermittent drip: the sound of a karst landscape still in formation.

We stop at the edge of a large room, about 60 feet across, and the sudden movement of a solitary bat catches our eye. Dark marks on the ceiling a couple feet above our heads and a telltale pile of guano on the floor indicate that a large colony of bats used to roost here. Researchers with Austin-headquartered Bat Conservation International think they were cave myotis, a species whose populations in the Hill Country have plummeted in the past few years due to the fungal disease white nose syndrome as well as extreme temperatures. The bat we just saw is a tricolored bat, also at risk: The species has been petitioned to be listed as endangered. It lives in tree cavities during the summer and hibernates in caves, including this one, in winter.

To protect the bats, salamanders, and other wildlife and plants at the preserve, the conservancy will limit public access to guided tours on select days in the near future. The first of these events is on National Public Lands Day this Saturday. If you didn’t get a spot to this event, bookmark the conservancy’s website or subscribe to its mailing list. The conservancy will offer at least one more public program at the preserve this fall and aims to host events—guided hikes, birdwatching, cave tours—quarterly in 2024.

The events are recreational but also serve as a call to action, Lindsey says. Nearby development is slated to bring 24,000 homes to the area in the coming years, making preservation of ecologically sensitive land even more critical.

“We’re struggling as a society to institutionalize land protection as a priority and as needed infrastructure,” she says. “Natural areas that are intact and functioning, and springs that are running, are as important as our highways, electric lines, and cell phone towers. Environmental work isn’t a charity. It’s not tree hugging. It’s a necessity for us to survive.”

I appreciate few things more than a well-designed park and a thoughtfully placed trail or campsite. But a preserve, with its emphasis on ecology over humans, offers an outdoor experience with a dose of humility. Instead of leading us on the longest hike or showing us the most sweeping view, Lindsey and Kostecke have trained our attention on three small but significant sites. I leave understanding more about the forces that have shaped the landscape in the past and, now that the land is preserved, the natural processes that will continue long after we’re gone.’