The

View

from

Warbler’s

Roost

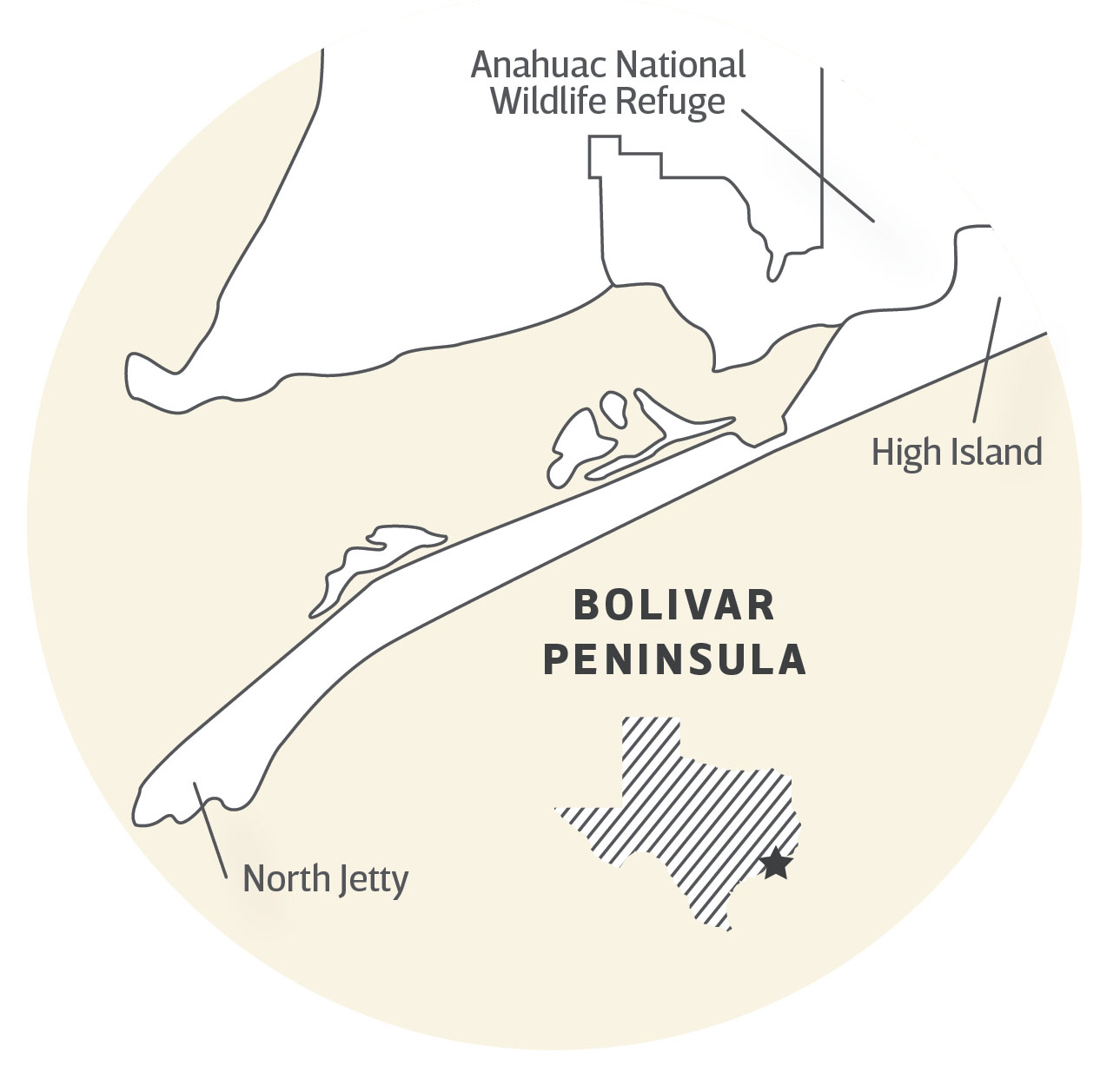

Surveying the Bolivar Peninsula

with renowned birder Victor Emanuel

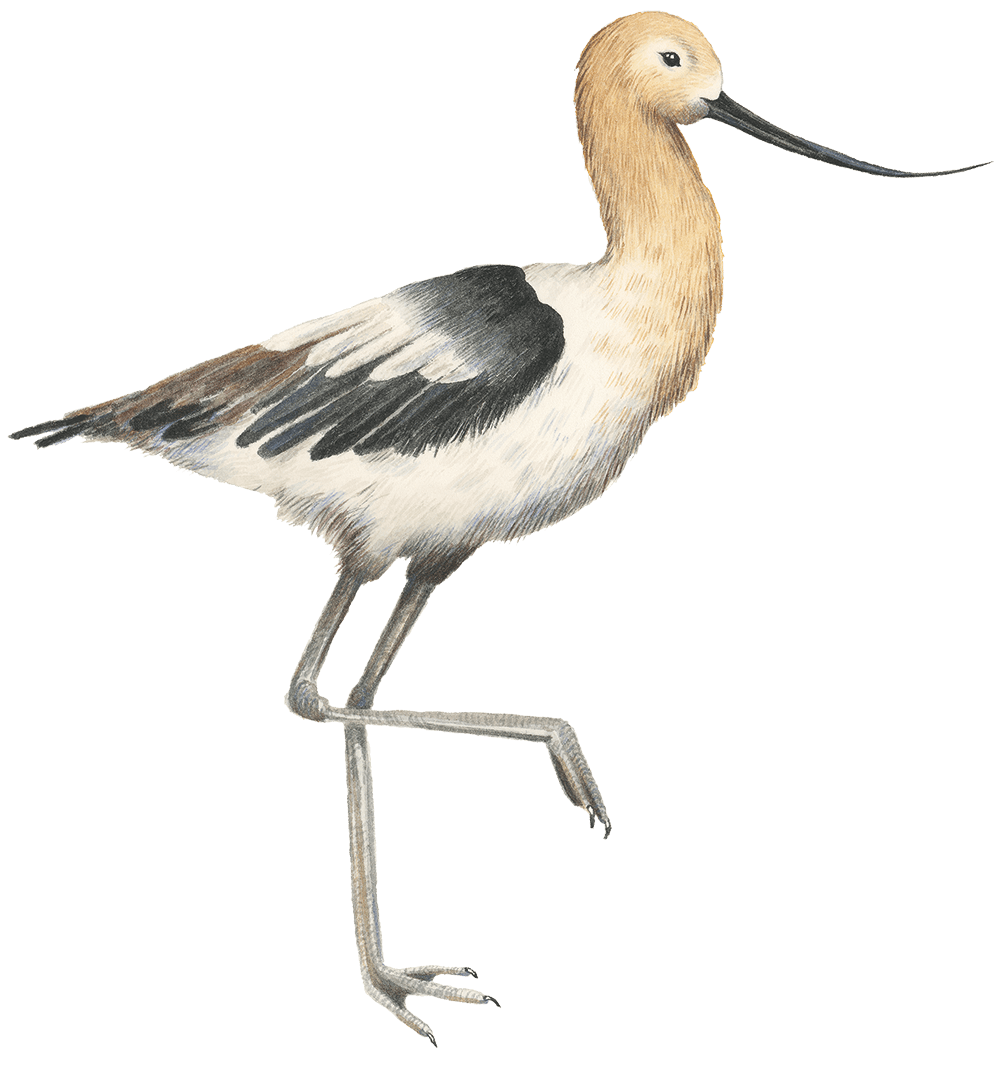

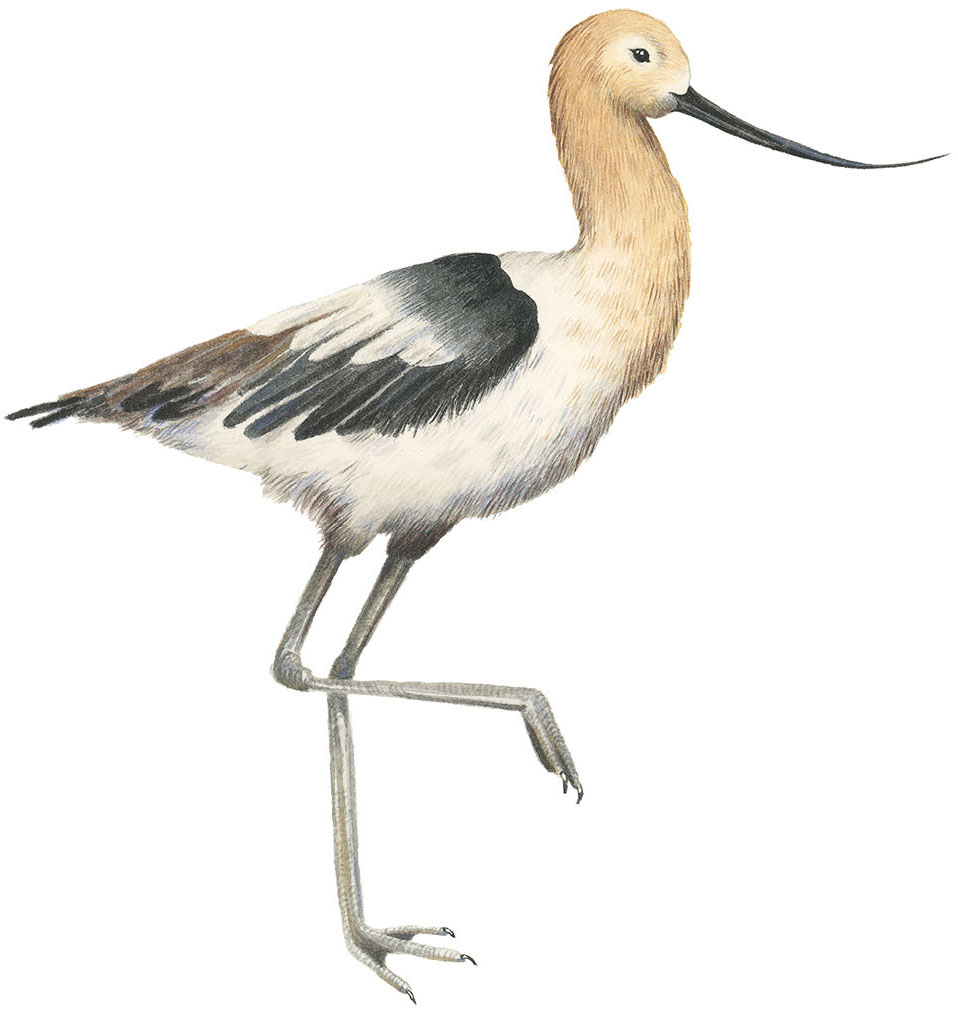

Day broke at the North Jetty on the Bolivar Peninsula as a multitude of shorebirds and waterbirds appeared out of the shifting shadows. It was late December and my husband and I, along with photographer Erich Schlegel, were walking along the 5-mile jetty just as the sun emerged over the eastern horizon to brighten the mudflats and marshlands, transforming the expansive landscape into brilliant swaths of golds, oranges, and yellows. As we walked, we observed silhouetted forms of American avocets and other shorebirds feeding in the shallow mud, producing a swelling symphony of movement with their curved, needle-like necks stitching the tidal flats for insects and other food.

The North Jetty and High Island, both on the Bolivar Peninsula, and on up to Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, feature some of the best birding in the country. For the novice birder, this 45-mile stretch, south to north near Galveston Bay, is an ideal starting place to experience the wonders of bird-watching for the first time. With its wide variety of landscapes and habitats—beaches, mudflats, salt marshes, and wooded areas—one can see warblers and other small birds during the spring migration, and an array of shorebirds, ducks, geese, and raptors year-round. The area is located in the migratory paths of countless birds that winter in southern Mexico, Central America, and South America, and fly north to their summer breeding homes.

“If you compare Bolivar to other coastlines in the United States, such as Florida, New Jersey, or Long Island, it’s one of the less developed parts of the entire U.S. coastline,” explains Victor Emanuel, a nationally renowned birder who makes his home in Austin and his second home in Port Bolivar. “In terms of the riches of bird life and other animal life, I consider the Bolivar area one of the best in the world. It’s a great place to visit throughout the year.”

The first time I discovered the wild beauty and magic of the Bolivar Peninsula was in late November 2015. I was collaborating with Emanuel on his memoir, One More Warbler. A native of Houston, Emanuel is the founder of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, a company that leads birding and natural history trips around the world. Emanuel’s illustrious career in birding goes back to 1959, when he landed on the national map after seeing the now-extinct Eskimo curlew in a field on Galveston Island, and writing an article about it.

Two years prior, he had established a Christmas Bird Count in Freeport, about 65 miles down the coastline from Bolivar. This is one of the many Audubon Christmas Counts that take place around the country, where citizen birders conduct a census of birds within a 15-mile-diameter area over a 24-hour period. The first counts were established in 1900 as a way to catalog birds rather than shoot them during the formerly popular holiday hunts.

Semipalmated plover. Photo by Kathy Adams Clark/KAC Productions

In 1971, Emanuel and his team reported 226 species, the highest total ever, and the breaking of this record elevated his status as a birder. The following year, journalist George Plimpton reported and wrote about the Freeport count and Emanuel for Audubon magazine, and the two became fast friends. Soon after, Plimpton introduced Emanuel to the writer and naturalist Peter Matthiessen, and over the next decades, Plimpton and Matthiessen traveled and birded with Emanuel on separate trips around the world—from seeing Emperor penguins in Antarctica to red-crowned cranes in Hokkaido, Japan. For years, Emanuel had considered a memoir, and after some mutual friends introduced us, he hired me to help write his book.

To be honest, at the project’s onset, I had gone birding only once. My dad and I had traveled with other family members to Point Pelee, a Canadian national park on the wooded northern edge of Lake Erie, to witness the warbler migrate north during May. Warblers are one of the hardest species to identify due to their small size, changing seasonal plumage, and quick movements. But they’re also one of the most rewarding thanks to their often-vibrant colors and variety (113 species exist in the Americas).

When I was growing up in southern Michigan, my dad had largely been a duck hunter, often spending weekends amid the marsh flats near the mouth of the St. Clair River. I rarely felt inspired to join my dad hunting (I went once with my sister, and we found ourselves almost numb in the partially submerged blind), but I was quickly drawn to birding. I enjoyed the fulfillment of catching sight of a small warbler—a flash of orange from a Baltimore oriole—and marking it off on my pocket-size checklist.

As Emanuel and I closed in on the deadline for his manuscript in 2015, we agreed it would be a good idea for me to experience the Texas Coast where he has spent much of his life birding. This includes Freeport, where he fell under the spell of birding as an 8-year-old, up to the Bolivar Peninsula, an 80-mile stretch.

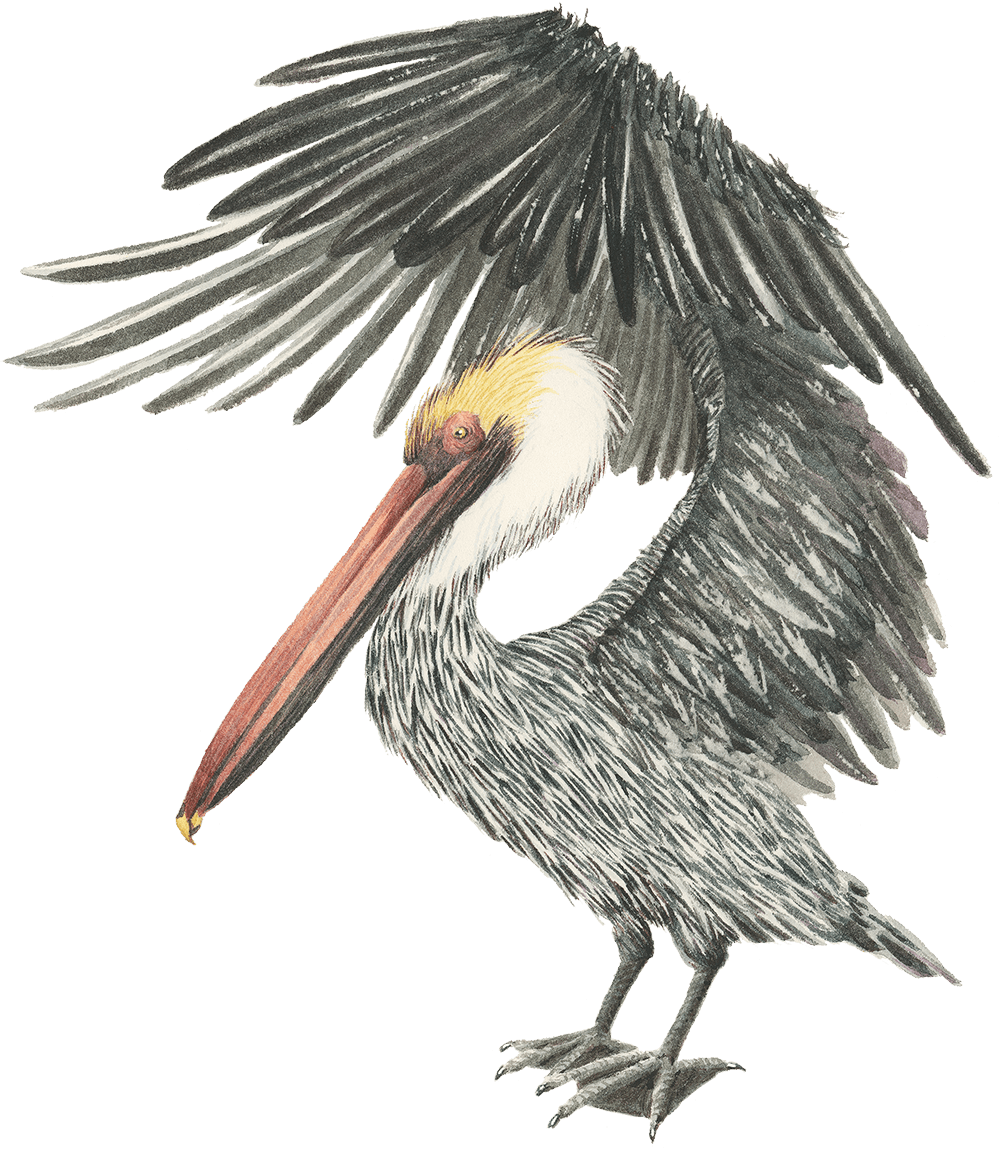

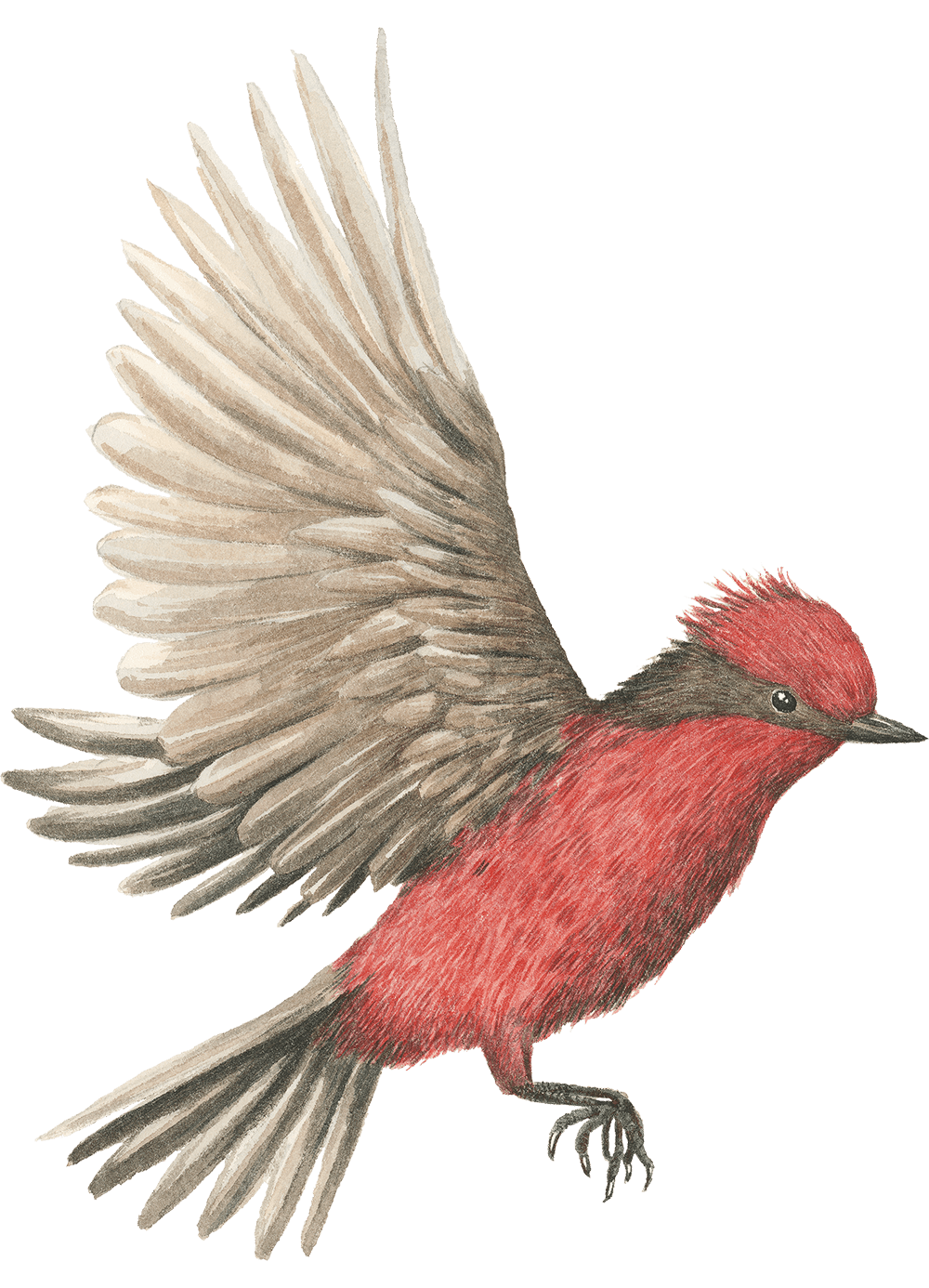

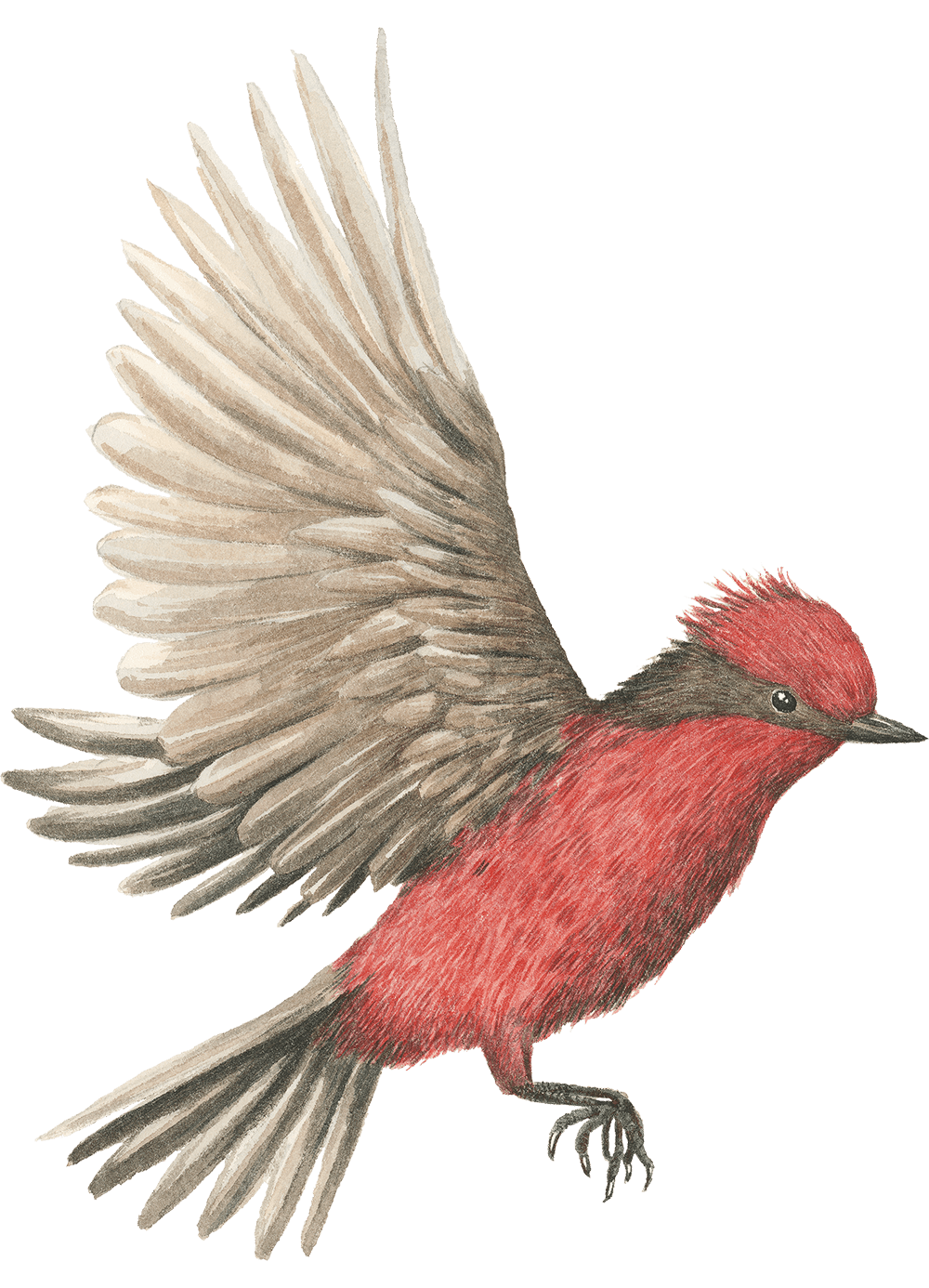

Vermilion flycatcher, Pyrocephalus obscurus

It might be easy for some travelers to miss the hundreds and hundreds of birds that feed, nest, and roost on the somewhat-desolate peninsula and its surrounding environs. That’s because most visitors take the ferry across the 3-mile Ship Channel and delight in the small pods of dolphins leaping through the water and the fleets of pelicans bobbing in the salt-laced air. They perhaps visit the Port Bolivar Lighthouse and return to Galveston. Upon first glance, there isn’t much to suggest that one is entering a birder’s paradise.

On my inaugural trip to Emanuel’s cottage in 2015, I was initially taken by the peninsula’s spectacular natural landscape juxtaposed with the distant oil refineries of Texas City and the oil rigs that perforate the horizon of the Gulf of Mexico. The meteoric arms of pump jacks are also a common sight in this area—a reminder to visitors that industry and nature sidle up right next to each other in this part of Texas. During two days of exploring, Emanuel and I identified more than 100 species of birds. It was breathtaking.

Emanuel’s modest yellow cottage, perched on 10-foot stilts, sits in an ideal location, just a few yards away from the nearby mudflats in the North Jetty community. Soon after buying the cottage, Emanuel’s friend Greg Laslay coined it “Warbler’s Roost,” inspired by the nickname, Hooded Warbler, bestowed upon Emanuel by his mentor, the naturalist Edgar Kincaid Jr. The cottage was relatively unscathed by Hurricane Ike, but evidence of the destruction—such as barren concrete foundations—still dots the sleepy neighborhood 11 years after the natural catastrophe.

The North Jetty is located at the end of 17th Street, just a few miles from the ferry landing at Port Bolivar. The Army Corps of Engineers built the jetty in the late 1890s, utilizing enormous pieces of pink granite from the Llano Uplift, a geological dome of Precambrian rock found in the Hill Country (the same source of the granite used for the Capitol building in Austin). Because the North Jetty stops ocean currents from carrying sediment away, the adjacent marshlands and mudflats are rife with decomposing plant material, creating an ideal environment for worms, shrimp, and other vertebrae, which are then eaten by the birds.

“At any time of year, you’re going to see a wonderful mixture of birds here: herons, egrets, shorebirds, pelicans,” Emanuel explains. “There’s always a lot going on by the jetty: huge feeding parties of birds, up to 10 to 20 different species.”

Often on a morning in the fall or winter, flocks of white pelicans can be found here resting and preening, and then at any moment, 200 to 300 birds can lift up and begin to fly in formation. “These birds have one of the largest wingspans of any bird in the world—up to 110 inches,” Emanuel says. “Almost as large as a condor.”

Often on a morning in the fall or winter, flocks of white pelicans can be found here resting and preening, and then at any moment, 200 to 300 birds can lift up and begin to fly in formation. “These birds have one of the largest wingspans of any bird in the world—up to 110 inches,” Emanuel says. “Almost as large as a condor.”

The Houston Audubon Society offers tours of the area and is a great resource for birders of all levels. Richard Gibbons, the society’s conservation director, suggests checking out the other side of the peninsula as well. He recommends two spots in particular: Horseshoe Marsh Bird Sanctuary and Frenchtown Road, where you might spot an American oystercatcher, with its long bright-red beak, or a clapper rail, a slender rust-colored bird with a curved beak. Gibbons proposes then driving about two and half miles to the Bolivar Flats Shorebird Sanctuary, a pristine stretch of beach protected and maintained by the Audubon Society.

American avocet, Recurvirostra americana

There, the expanse of shoreline and prairie might appear just like any other beach along the Texas Coast, but after a leisurely walk, the unexpected beauty quietly unfurls before your eyes. “There is a lot to see here, depending on the day,” Emanuel says.

Small armies of shorebirds—willets, dowitchers, and plovers—swiftly skitter across the damp sand. In addition, several species of terns can be found along this shoreline. “There are very few places in the world where you can see eight kinds of terns in the same area,” Emanuel says. “Sometimes you can see 100 or 200 terns at the edge of the water.”

One afternoon during our December trip, platoons of white pelicans flew overhead. My husband and I noticed a pair of horned larks, a striking songbird with horn-like tufts of feathers on its small head, flitting along the sandy border of the prairie grasses. A Northern harrier, with its long broad wings and white patch at the base of its tail, glided above the swaying tips of the savanna. On another afternoon last March, we spotted a reddish egret prancing along the nearby shallow pools. It hopped and jumped and spun while it foraged for fish, as if performing a beautiful ballet for any passersby willing to stop and look closely.

During April, high island is one of the best spots to take in the warbler migration and has been described on local billboards as the bird capital of the United States. There is veracity to this boast: About 10,000 birders travel to High Island during the spring (peak migration takes place between mid-March and mid-May). About half of these visitors are from Texas, while the other half comes from the rest of the U.S. as well as nearly 20 additional countries.

Roseate spoonbill, Platalea ajaja

High Island technically isn’t an island but comprises an uplifted salt dome. Its coastal marshes, enormous live oaks, dense woodlands, and water drips supply much-needed refuge for the migratory birds that have just completed the 700-mile-plus flight across the Gulf of Mexico. During this peak season, more than 200 different species can be spotted in Boy Scout Woods, Smith Oaks, and other areas located on High Island. Throughout the spring and summer months, many breeding birds, such as roseate spoonbills, cormorants, and egrets, can be found nesting at The Rookery, a question-mark-shaped island in the middle of Claybottom Pond. Alligators lurk in the surrounding water, where they play a vital role in protecting the birds from raccoons and other predators.

In preparation for the migration season this year, the Houston Audubon Society is building and updating its amenities. This includes new public restrooms, which are being installed in the 1920s pump house at Smith Oaks, right at the entrance to The Rookery. Also, a new accessible walkway will extend up 18 feet into the forest, giving visitors uninterrupted views of the southwest corner. “Not everyone has binoculars,” Gibbons says, “so they can get a chance to see the nesting birds and even the smaller birds up in the canopy.”

In Smith Oaks Sanctuary, visitors will notice the lush canopy of the giant oak trees and how it’s more pristine than the foliage of the nearby Boy Scout Woods. That’s because this woodland area was less damaged by Hurricanes Ike and Rita, due to its elevation. “Smith Oaks’ star has brightened a little because much of the cathedral is gone from Boy Scout Woods,” Gibbons explains.

From High Island, take a drive to Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, a 37,000-acre preserve 17 miles northeast. During our first trip to Anahuac, Emanuel made continual stops along the shoulders of the road to take in the wide array of raptors found on the bends of utility wires and poles—white-tailed kites, peregrine falcons, crested caracaras, and others.

In Anahuac, a two-and-a-half-mile loop encircles Shoveler Pond, a freshwater impoundment seething with waterfowl, shorebirds, and occasional alligators. There are several opportunities to park, observe wildlife, and stroll along a boardwalk that leads into the heart of the marshlands. During a recent visit, a small grouping of roseate spoonbills, alongside iridescent green ibises, fed in the patchwork of reeds and grasses.

As we departed Anahuac, enormous flocks of snow geese lifted up from surrounding rice fields and circled in a massive swirl before returning to the ground. The collective sound of their wingbeats filled the air like electricity. It was a spectacle of natural brilliance—ephemeral and enduring at the same time. I knew my dad, who had passed away a month earlier, would have been equally thrilled by such an awe-inspiring sight. As the hundreds and hundreds of snow geese eventually rested onto the open field, my dad—and his love for birds—was very much with me.

“I think being out in nature is a healing experience,” Emanuel says. “Whenever it comes time to leave Bolivar, I don’t want to leave. Every day is different.”

Early-Bird Special

First-time visitors can easily take in the natural riches of this particular stretch of Texas Coast. If you travel by ferry, arrange your schedule so you arrive first thing in the morning. The ferry runs 24/7 and is free.

Getting Around Port Bolivar: Once you disembark the ferry from Galveston, drive along State Highway 87 for a mile and a half and take a right on 17th Street. When you arrive at the end, park and take a walk along the North Jetty. Then, to get to the Bolivar Flats Shorebird Sanctuary, drive two and a half miles along SH 87 to Rettilon Road, a sandy two-track path. Turn right and drive along the hard-packed shoreline until you reach the vehicular barriers, or large weathered pylons, and park. (Note: Drivers need to purchase beach passes to drive on the beaches of the Bolivar Peninsula, which are available at local convenience stores.) Travel further east on SH 87 for about 25 miles to High Island. For Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, take State Highway 124 and then turn left onto Farm-to-Market 1985 and, after about 17 miles, look for the sign leading you to the wildlife refuge.

A Few Tips: During the spring migration, the Houston Audubon Society offers bird walks every day of the week. For more details, visit houstonaudubon.org. Also, once you arrive at Bolivar, pick up a copy of Gulls n Herons, a newspaper published by the Galveston Ornithological Society, which provides helpful tips for birders. For a remote visit, check out the Bolivar Flats Bird Cam.