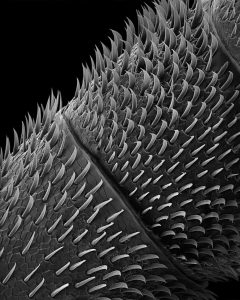

Close-up images of bees, like this one, can be found in the Luci and Ian’s Family Hill Country Garden at Waterloo Park in downtown Austin.

Seeing Bees at Waterloo Park

Seeing Bees is open daily during park hours through May 23.

Address: 500 E. 12th St.

Park Hours: 5 a.m. to 10 p.m.

Admission: Free

Website: austintexas.gov

A path winds down the hillside in the Luci and Ian’s Family Hill Country Garden at the south end of Waterloo Park, just a couple blocks from the Texas State Capitol. As the path takes visitors beneath the shade of trees and past lavish swaths of native plants, bees busily work patches of flowers. Along the way, eight 4-by-5-foot panels bear dramatic black and white images. It takes a moment to realize the images are bees, too, only enlarged to a size thousands of times bigger than the actual insects.

These images were shot by world-renowned, Austin-based photographer Dan Winters for Seeing Bees, an art installation in the newly transformed 11-acre greenspace in downtown Austin. The installation remains on view in the garden until May 26.

Bees are not the usual subjects you might associate with Winters. The long list of people who have sat for him includes famous names ranging from Bono and Willie Nelson to presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama. But bees have become a favorite of his to shoot, using not a camera but a scanning electron microscope, or SEM. Typically a tool for scientific study, an SEM uses electrons instead of light to form images that magnify their subject by as much as a million times.

Winters began experimenting with SEM images in the mid-1980s but his history with bees goes back to 1971, when he became a beekeeper in Southern California at the age of 9. He sold his hives when he went to Moorpark College in California to study photography and then to Germany’s Ludwig Maximilian University to study filmmaking. While working as a magazine photographer in California and New York, he amassed an impressive portfolio, and his work is now in permanent collections at the University of Texas’ Harry Ransom Center and the Witliff Collections at Texas State University. He moved to Texas in 1999.

Photographer Dan Winters captured bees up close using SEM technology.

With his experience using SEM, he published an article and SEM images in Texas Monthly in 2008 about the threat of colony collapse disorder, which is when worker bees in a hive abruptly disappear.

“Colony collapse really concerned me, and I wanted to do an awareness piece,” Winters says. “I worked on the images a couple of months here and there, after hours on the scanning electron microscope at the University of Texas. Bees are in trouble, and I needed to get it on people’s minds.”

Then his wife, Kathryn, gave him a beekeeping class at Round Rock Honey as a birthday gift, and Winters returned to his old hobby. He gave a few of his SEM images of bees to Round Rock Honey owner Konrad Bouffard, which led to the idea for an exhibit.

Bouffard says he has a decadeslong interest in public art and that previously owning an art gallery taught him that people need a point of reference to make art relevant to their lives.

“Instructional art offers something deeper than aesthetics, and that is what people are looking for,” Bouffard says. He knew of Wild Spirit Wild Places, a nonprofit established by Desert Door distillery in Driftwood to preserve wild lands in Texas and called its CEO, Karen Looby, about working on an exhibit. She suggested it be at Waterloo Greenway.

“We met with the people at the park, and it was an instant decision,” Bouffard says. “The caretaking that goes into their grounds, the fantastic pollinator garden, the native plants—it is a best-in-class park.” The park has more than 90,000 native plants, including a collection of certified pollinator habitats.

Bee or cactus? A scanning electron microscope, or SEM, can magnify the surface of an object millions of times.

With Round Rock Honey also on board as a partner, the project secured financial support through H-E-B and international skin care and fragrance company Guerlain. Both companies support conservation and efforts to increase public awareness and environmental stewardship.

Winters expects people to be surprised by the size of the images, noting that a bee’s head is roughly 2 or 3 millimeters long, or less than an eighth of an inch. “To put that on a panel that is 4 feet by 5 feet, you see it in a way you never could otherwise,” he says. “The images are incredibly revealing to me, and the park is a really great place for the exhibit. I had never done an exhibit outdoors before and it is a unique experience, seeing these large-format, fine-art prints in a setting that is so beautiful.”

It is, he adds, a lot more work than the usual photography exhibition. “The process to create these images is tedious and expensive. It requires a lot of precision and hours of work to mount a specimen. The insects have to be dead, unfortunately, so I collected ones that were already dead. I felt it was for the greater good.”

That greater good, for Winters, is increasing awareness of and appreciation for the roles that bees play. After all, native bees and honeybees help preserve balance and biodiversity in nature and almost 90% of the world’s flowering plants depend on them for pollination. He hopes the images created for Seeing Bees drive home that important fact in a big way.