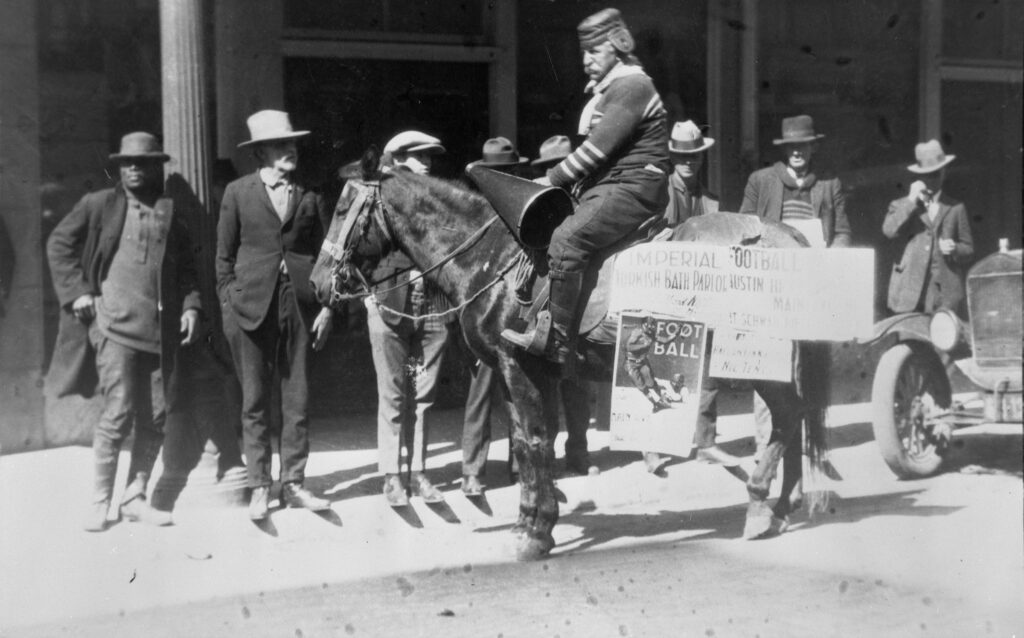

Julius Myers seated on a horse and wearing a football uniform in San Antonio, circa 1920. Signs on the horse advertise a football game in San Antonio. Courtesy UTSA Special Collections.

“Ladee-eez ’nd Jumpm’n,” bellowed San Antonio’s beloved town crier, Julius Myers, as reported in a 1920 issue of American Magazine. “Don’t forget th’ Hot Times at Hot Wells! Hot Dogs, Hot Tamales, ’nd Hot Baths!”

Historians have ventured that Myers (also spelled as Meyer and Meyers, depending on the source) was the last town crier in Texas. Some even claimed he was the only informational street shouter—a colonial profession imported from the Old World—in the entire country. The late San Antonio researcher (and National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame inductee) Frances Kallison declared in a speech she gave in 1982 that “Megaphone Myers,” at the time of his death at the age of 62 on Sept. 18, 1929, was the lone extant embodiment of his loudmouth fraternity in the entire Western Hemisphere.

In the opening quote above, Myers advertised the Alamo City’s Hot Wells Hotel and Spa—a health resort once visited by the likes of Will Rogers, Charlie Chaplin, and Teddy Roosevelt. The Hot Wells ruins were recently acquired by Bexar County, stabilized, and reopened to the public as a park. Riding his placard-covered horse named Tootsey, Myers also ballyhooed for shops, cafes, sporting events, and cultural affairs. When he publicized silent films, he dressed in character as a cowboy or a sheik.

Theatricality was part of Myers’ DNA. He was born in New York in 1866 to German-immigrant parents who, according to Kallison’s research, had been roving thespians in Prussia. Afflicted with respiratory issues, a 20-year-old Julius did what many health-seekers did at that time and headed for Texas in 1886. Settling in Luling, he opened a grocery store/restaurant, married, and started a family.

At some point while living in the Caldwell County hamlet known as the “Toughest Town in Texas,” Myers founded the Southwestern Advertising Company. By 1908 he was a member of the Texas Bill Posters Association, attending their seventh annual convention in Houston. The next year, his Luling public relations firm was engaged by the famous Lydia Pinkham medicine company to hype its herb-and-hooch remedy, Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound.

In 1912, perhaps feeling a need for a more robust form of promotional communication in a faster-paced environment, Myers moved his family to San Antonio. There, he and Tootsey became favorites of tourists and townies alike as they traveled from plaza to plaza, his booming voice echoing through the streets. A 1920 Census identifies him as a “public announcer for the city,” and old Alamo City newspapers chronicle the crier’s many gratis performances for local charities. His assistance to the Red Cross proved invaluable during the historic flood of 1921.

Eventually, the mass-market power of radio and the inner-city infestation of the automobile conspired against Megaphone Myers. “The town criers had outlived their usefulness and were apparently irritating the general public a bit,” says San Antonio historian Maria Pfeiffer. A 1926 city ordinance banned his profession, but Megaphone was allowed to ballyhoo baseball games in 1928, so long as he replaced Tootsey with a bicycle. Some 500 San Antonians attended his funeral in 1929.

Was Julius Myers really the last town crier in Texas? A 1926 photo feature circulated in newspapers throughout Texas reported that to be the case. Mineral Wells’ Foghorn Clancy had given up civic hollering for rodeo announcing around the turn of the century, and Uncle Syl Tabor had long ceased officially shouting the news while riding a mule down the streets of Brownwood.

But then there’s one Albert Schultz. For a dozen years, Houstonians knew him as the ubiquitously oratorical Foghorn Kelly. “He was on the streets rain or shine,” reported the DeLeon Free Press in his obituary, “wearing a big ten-gallon hat and blaring the advantages of first one thing and then another through a huge megaphone.” The real name of Houston’s “unofficial town crier” wasn’t known to many until his death in 1933. He outlived Myers, but did he out-cry him? Give us a shout if you know.