Courtesy Getaway House

Surrounded by windows and white pillows while in bed at my tiny cabin, I think of the liner notes to Bob Dylan’s album Desire: “These notes are being written in a bathtub in Maine under ideal conditions…” Here at Getaway Hill Country, I am also writing under ideal conditions: quiet, simplicity, good coffee. The only distraction for me here is a red cardinal who has twice this morning flown into the expansive window next to me and then fluttered back to the scrubby live oak a few yards away.

For the past year, distraction has been a particularly fierce tyrant. Since my children left their in-person classrooms in March 2020, if I wasn’t actually being interrupted by requests for smoothies or cries over online school glitches, I was always anticipating that interruption. My nervous system, as many of ours were during COVID-19, was forever on high alert.

My office at home is at the top of a stairwell; it doesn’t have a door. I can hear everything that happens downstairs, which, since the pandemic hit, has been considerable: my son moaning about schoolwork he lost on his laptop; the sound of my 15-year-old daughter crying while re-watching Grey’s Anatomy during online class; the dog whining. These sounds launch a cascade of worries. There’s no way my daughter could be paying attention to her teacher when hot Dr. Derek Shepherd just died, even if she’s seen that episode multiple times.

Cal Newport, a writer who leads the crusade against distraction in our prevailing monkey-mind culture, wrote in a recent New Yorker article, “Performing useful cognitive work is a fragile endeavor, one in which environment matters.” He says that even just walking past your laundry basket can set your brain off in a distraction spiral because that basket is “embedded in a thick stress-inducing matrix of under-attended household tasks.”

I’ll admit, when I first drove up to Charles (my cabin is named Charles; all of the cabins here are named after Getaway employees’ and friends’ grandparents—Benita, Gary, Arlene, Jacques), I was surprised by just how tiny it looked. I wasn’t sure I wanted to spend two days in a 120-square-foot box. Turns out that yes, I very much do. Because once inside, Charles doesn’t feel small; the immense windows make you feel like you are living amid wildflowers and oak trees.

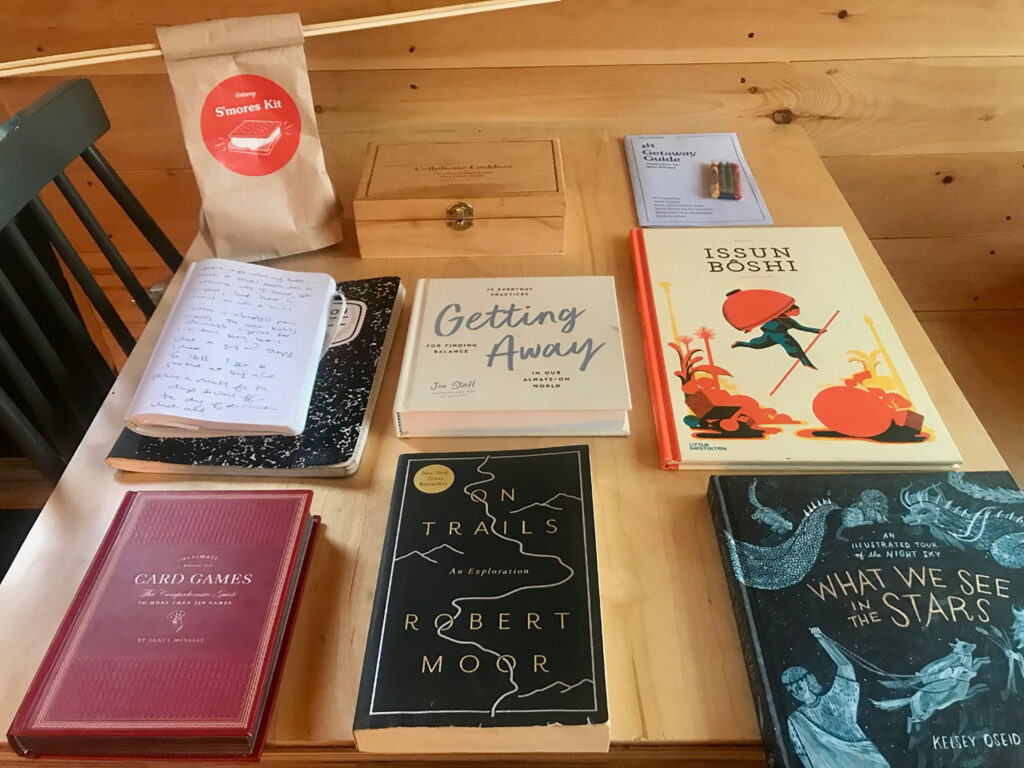

A selection of books offered in a cabin at Getaway Wimberley. Photo by Clayton Maxwell.

It takes some adjusting to become undistracted. The deeply wired itch to check messages takes time to fade away. But not that much time. In a place like this, with my vacation auto-reply on, it’s easy to get unhooked from my addiction to emails and texts, and instead get hooked, for example, on how good the cherries I brought for breakfast taste, cold from a night spent in that cute fridge, and how fun it is to spit their pits into a blue tin bowl.

Did I mention there are no mirrors? Thanks, Getaway, you have freed me from another, as Newport writes, “stress-inducing matrix.” Despite having swam in Cypress Creek, just a 15-minute drive away, each day of my stay in Wimberly, I haven’t used my hairbrush once.

But I have read a lot, and the book selection tucked away on the cabin shelf is primo, with books like Kelsey Oseid’s What We See in the Stars, Robert Moor’s On Trails, and Getting Away, 75 Practices for Finding Balance in our Always-On World written by Jon Staff, the co-founder and CEO of Getaway.

This last book is an easy-to-digest, friendly resource for taking care of yourself, your relationships, and your mental health in a world that’s always demanding your attention in eight places at once. Staff explains why he founded Getaway: He and co-founder Pete Davis’ favorite memories were of trips that allowed them “…to escape the stresses of our daily lives both physically and mentally, enabling us to reconnect with a version of ourselves that feels truer to who we really are—or, at least, aspire to be.”

He wanted to offer that to others. Deliberately, there is no Wi-Fi at Getaway Hill Country, and each cabin comes with a cellphone lock box. Since his first Getaway launched in 2018, Staff has opened 14 outposts across the country, with three in Texas—near Wimberley, LaRue, and Navasota—all easy drives from Austin, Dallas, and Houston, respectively. With cabins starting at $99 dollars a night, thousands of people can access a taste of their own Walden Pond for a night. They also offer free one-night fellowships for artists of all kinds.

In his book, Staff offers 75 practical tips to help avoid feeling overwhelmed. Some are things most of us know we should do, like meditate and turn off notifications; some feel hard to do, like auditing your belongings and taking a digital Sabbath; and some are just fun, like listening to an entire album start to finish. His tone is playful, not preachy—and I have no doubt that if I did a few more of the things on this list, my nervous system would thank me.

Staff, of course, is big on nature, and highlights the health benefits of hikes and forest bathing, writing that “trees and plants release chemicals called phytoncides, which boost immune function by increasing the activity of the white blood cells our body uses to fight tumors and infection.”

The Getaway Hill Country, not far from two of Texas’ most treasured swimming holes, Jacob’s Well and Blue Hole, is well-situated for maximal phytoncide exposure. Both spots require reservations for swimming (here and here), but they also have meandering trails, through prairie grass, oaks, and cedars. No reservations are needed to hike. And while Staff does not specifically write about swimming, I am quite certain that backstroking through the cool waters of Blue Hole, with its canopy of chlorophyll-green cypress gazing down upon you, is a sure way to unplug from the “always on” world.

If you don’t want to only eat at your tiny cabin, you can brave civilization in downtown Wimberley, itself pretty tiny. The pizza at Community Pizza and Beer Garden, particularly the pesto and prosciutto version piled high in lemony arugula, is superlative. The tried and true Wimberley Café serves burgers and salads, and, if you like Texas wines, try the Newsom Vineyards High Plains Tempranillo, one of the best I’ve had.

On my second morning in Charles, I wake mildly euphoric, although I can’t pinpoint why. I consider something I read in the aforementioned article, about how “the familiar snares our attention, destabilizing the subtle neuronal dance required to think clearly.” Maybe that’s it: Removed from my familiar and far too busy environment, my mind woke up today clear and wide, like the big Texas sky that surrounded me while still in bed in my tiny cabin.