In the corner, a man in a pink polo shirt talks quietly into his phone. Two other men, still wearing their golf clothes, share cocktails and laughs on the couches by the entrance. Behind the bar, the two bartenders on duty are recounting a few of their favorite stories about the place: how the building used to be the Pearl brewery and this room was the bottling room, how the chandelier was made with the brass wheel from the old bottle-labeling machine, how a certain lead actor from the Lonesome Dove miniseries likes to come in and sit in a corner upstairs, away from the crowd. As soon as the bartenders see the actor, they start making his margarita.

This is the Sternewirth Tavern & Club Room at Hotel Emma, in San Antonio. The bar’s name comes from the “Sternewirth Privilege,” an 1800s tradition that entitled employees of breweries to free beer during the workday. It’s the kind of place that shows up on all sorts of Best Hotel Bars lists, understandably. On top of the celebrity sightings, custom cocktails, and modish décor—some of the giant brewery tanks have been converted into booths—you can also take your drink to one of the leather chairs in the massive, two-story, 3,700-volume library.

This is the first stop on my three-day journey to hang out in a few destination hotel bars in Texas, to commune with strangers and hear fantastical stories, to experience the fascinating interactions that tend to occur in the tomorrow-be-damned atmosphere a great hotel bar conjures. After two hours on a stool at the end of the bar, though, I unfortunately don’t have much.

A few small groups come and go, but it’s been a slow, quiet night—that is, until a voice behind me says something along the lines of: “You are holding my possessions hostage!” And, “I’ll be forced to turn the matter over to the police!”

When I turn around, I see a man in his 40s, wearing tennis shoes, exercise clothes, and a baseball cap, and he’s ranting into his phone—leaving a message for someone.

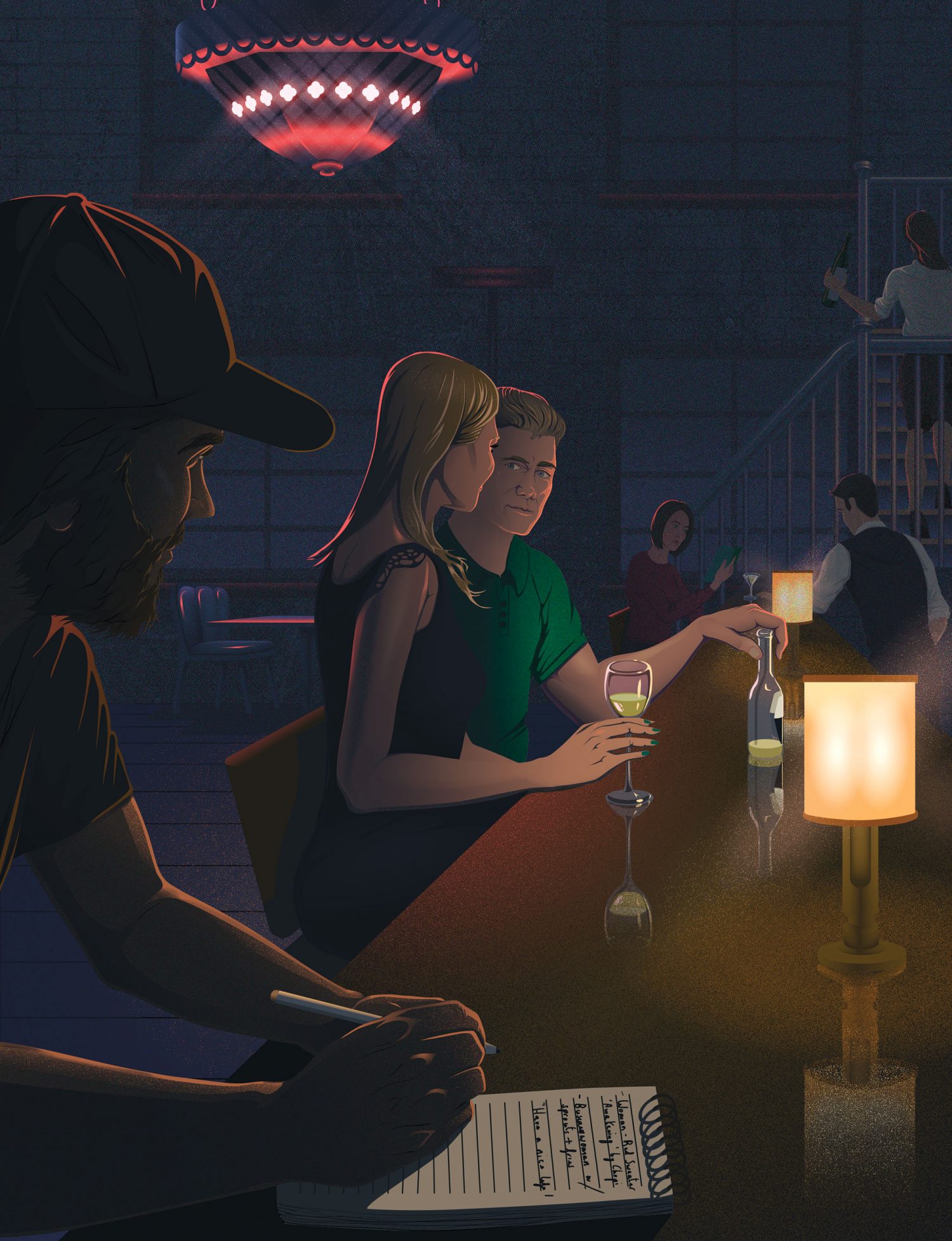

He puts his phone down, exasperated. Seeing that the bartenders and I have taken notice, he tries to explain. He’s from Orange County, California, he says. He’s in town visiting his girlfriend. They had a fight, he left and came here, and now she’s not answering her phone. He’s not completely sober and doesn’t get into much detail, but he’s worried about work meetings he has back home tomorrow afternoon, worried about his computer and his clothes, worried about his whole relationship.He orders me a drink, and one for himself, and he asks if anyone can help distract him.

“Tell me a story,” he says. He’s tense, trying not to look at his phone.

I’m sure I can come up with something, but before I get the chance, the barback, a barrel-chested man in his 20s, declares, “I have a story.”

The barback says a few years ago he dated a woman he met at the gym. She was 18 and had a young kid and no car. Pretty soon this guy was driving his new girlfriend everywhere she needed to go. At some point, he explains, he had some sort of seizure and ended up in the hospital.

“Oh no,” says the man from Orange County.

“That’s when she ended it,” the barback says.

“Right there in the hospital?” Orange County asks.

The barback takes a breath.

“Over the phone,” he says.

The man from Orange County grimaces and finishes his beer. Soon, though, he’s back on his phone, sending his girlfriend a series of frantic texts. It’s five, then 10—a mix of insults and threats to call the police or their mutual friends. Then he calls again, leaves another angry message. Then more texts.

At least three people are watching now.

“What do I do?” the man asks.

His computer! His clothes! His meetings!

“It could be worse,” the barback says. “You could be in a hospital getting broken up with over the phone.”

This seems to calm the man from Orange County. He quietly pays his tab and disappears into the night. The most interesting story of the evening turns out to be a truncated, unresolved excerpt.

Oftentimes, a good hotel bar has soft lighting, unobtrusive music, and delicious drinks. It’s populated by a collection of travelers: everyone in the middle of their own adventure, all crossing paths by happenstance. Some of them are in town for work, some for vacation, some for reasons nobody could guess—and now they’re all trying to unwind from something. All of that, plus alcohol, makes the patrons of a hotel bar more congenial than they might be otherwise, more likely to open up about the most interesting parts of their lives.

The conversations at a hotel bar, between total strangers, are as real as a puff of smoke. As soon as the wind blows, it’s almost like they never existed at all. The people here probably won’t meet again. And even if they do, they may never again acknowledge what was said over an untold number of cocktails with a stranger.

There’s something magical about that. It’s a chance to understand your fellow humans in new ways, with the freedom of anonymity. It’s a chance to confess to someone you’ll never see again. I travel a lot and end up in a lot of hotel bars, which means I’ve listened to strangers tell me things their best friends and closest family didn’t know. Ambitions. Predilections. Personal failings.

A hotel bar is also an opportunity to be anyone you want for a few hours. If you’re usually loud, maybe now you’re quiet. If you’re usually reserved, maybe now you’re lively. Maybe you’re not someone worried about a big project at work or an argument at home or what’s in the bank. Maybe, just for a moment when it doesn’t matter, you’re the best, funniest version of yourself. Maybe, among strangers, you’re someone who’s already accomplished some of the things the real you wants to do in life.

At least one time, I did that and it came true. I was 24, an aspiring but mostly unpublished magazine writer, sitting in the bar at the Worthington Renaissance Hotel in Fort Worth. The granite bar and wood paneling and perfume-scented air made me feel like I’d somehow stumbled into a private club. I remember a bartender telling people that a certain Indiana Jones star came in there often, something about parking his plane somewhere close.

Conversation among the four or five strangers brewed in the way it almost always does in a hotel bar, and soon there were short introductions and explanations of why we were all there. One young man said he was an officer in the Air Force, in town for a meeting. One woman said she was in Fort Worth on vacation with her family and needed a few minutes away.

I was there because it was my birthday and my then-girlfriend splurged on a discounted room and subsequently fell asleep before 10 p.m. For some reason though, I didn’t say any of that. Instead, I said I was there because I’d won a writing award. Which wasn’t true at all. When the vacationing mom asked what I’d written about, I mumbled something cringeworthy about “documenting the downtrodden.” A few people congratulated me.

I might have forgotten about that night, and that strange lie, except a year later I was in a different hotel bar, and I had just won an award (and a check!) for my writing. It was for a story about the lives of struggling people living in the margins of society. It felt like, in the magical perfumed air of that swanky hotel bar in Fort Worth, I’d somehow conjured my own future.

Another time, at a hotel bar in Washington, D.C., a bartender saw my beard and long hair and asked if I was a musician. I have absolutely no musical talent, but for basically no reason I lied and explained that yes, I was “not Mumford, but one of the Sons.” I wasn’t too familiar with the band’s catalog, so I was hoping there wouldn’t be any follow-up questions. A few years later, at a different hotel bar in a different city thousands of miles away, I started talking with a stranger who happened to be working security at a concert the next night. He asked if I’d be interested in free tickets. The band: Mumford & Sons.

That’s the kind of magic I had in mind when I set off on this trip. Three nights, three cities, three hotel bars with that behind-the-velvet-rope vibe—and three chances to bond with my fellow travelers. Trying to convince a man at Hotel Emma not to escalate a domestic dispute is a modest start.

The second bar I visit is at the Driskill Hotel in downtown Austin. In the lounge, the head of a gigantic longhorn steer hangs above the fireplace, looking over a sea of soft leather couches, a bronze tin-stamped ceiling, and an 8-foot-wide sculpture of an Old West scene. The Driskill is probably the most famous hotel in Texas. Opened in 1886, the entire building has that unmistakable frontier feeling—the barstools are even covered in cowhide. One of the bartenders informs me of the legend that the lobby was the site of a gunfight between two attorneys in the early 1900s.

Tonight the couches and tables are filled with business travelers eating dinner and watching basketball. There are a few pockets of 30-somethings but the crowd leans more toward older men in slacks and polos. At the bar, a few couples stop in for a pre-dinner drink. A woman in a red sweater is sipping a martini and reading The Awakening by Kate Chopin. A man two seats down from her, wearing jeans and boots, eyes the game on TV while drinking his bourbon. A business woman, scrolling through her phone, has a glass of rosé and a dinner of Brussels sprouts and french fries.

I notice several lamps around the bar are made of old revolvers. The woman with the Brussels sprouts and a couple in their 40s sitting to her left all listen in as one of the bartenders explains that the guns are all Colt 8-shot revolvers from the 1850s, made for the U.S. Navy but sold to and used by the Texas Rangers.

Soon the Brussels sprouts woman asks if anyone wants some of her french fries; then there’s some vague discussion of aging and how being an adult is one big mix of sprouts and fries and wine. After two or three glasses, she asks the bartender if she can just take the rest of the bottle up to her room. Before she leaves—and I’m not sure how the conversation got here—she announces to anyone within a small radius: “If I finish that bottle, I’ll end up naked, but I will make my 8 a.m. meeting!”

She adds, as she walks away, “Have a good life!”

Within a few minutes there’s a new group: two women and a man, all in their late 20s or early 30s. They order three Aperol spritzes. Then three vodka martinis (called “batinis”). One of the women explains that her friends grew up Mormon and didn’t drink for most of their lives. Now they do, and while they’re in Austin she’s helping them try different mixed drinks to see which ones they like. Neither of the former teetotalers finish their martinis.

I’ve been at the bar for about two hours, watching people cycle in and out, when a young woman walks in wearing 5-inch heels and a long dress. She sits two seats away from me, tells the bartender she’ll have what she usually has, and receives a glass of white wine. She pays from a roll of one-dollar bills. She introduces herself, says she’s a student at the University of Texas who lives downtown. Her major: the very vague-sounding “business administration.”

In a hotel bar, I remind myself, everyone has secrets. Some people are working. Some are out for adventure. For some, it’s both.

I watch her make conversation with the man in jeans and boots. She’s quiet, but I hear her mention that she likes Miami and Las Vegas. Then she starts a conversation with another man, sitting on the other side of the bar. Then, after half an hour or so, she finishes her glass of wine and heads toward the hotel lobby, off to look for magic elsewhere.

The final night of the hotel bar tour is at the Adolphus in downtown Dallas. As I drive up Interstate-35, replaying the faces and stories from the last two nights in my head like an imaginary podcast, I start thinking more about why I like hotel bars so much. I understand that it’s about the taste of luxury, the one-night-only friendships, the titillation that comes from a secret with a stranger—but why is that so appealing?

On one level, it’s a nice reminder that, despite our loneliness, humans are deeply connected and interdependent in ways we still don’t fully understand. It’s why you can be moved to tears at a funeral for someone you’ve never met. It’s why friends often get pregnant in groups, why suicides happen in clusters, why the words of a stranger can completely change your mood. In hotel bars, you can feel that connectedness in the scented air.

But it’s also an escape from reality. It’s a reprieve from the dreads and regrets of our everyday lives.

All three bars on this trip blend haunting history with modern opulence: a blue-collar brewery-turned-five-star-hotel in San Antonio, a lavish saloon for powerbrokers in Austin, a landmark of generational wealth in Dallas. Built in 1912, the Adolphus has hosted presidents, monarchs, and magnates.

Walking in, I notice the glowing fireplace in the French Room Bar and the lighting in every room: dim enough to feel like the hues of a dream. The Adolphus actually has two bars on the ground floor. I find a spot at the City Hall Bar in the social lobby and learn there’s a conference in town, something to do with the future of plastics.

It seems like there are 20 different conversations happening here, most of them weaving together, overlapping. One man wearing a thick gold bracelet says he’s from Michigan. There’s a woman from Maine. A group of businessmen from Collin County. Two guys from Arizona see me taking notes in a small notebook and drunkenly joke that I must be “writing raps.” Some of the men and women here are corporate leaders. Some are aspiring entrepreneurs. It makes for a chaotic blur of names and places and micro-conversations.

Somehow I start a side conversation with an artificial-intelligence expert from Austin, here for the conference. There are jokes about robots uniting to overtake humanity, but the AI guy says he doesn’t think that’s likely. He describes some of the most recent breakthroughs in the industry in ways that make me feel like I actually sort of understand a little bit.

Soon this AI guy and I are talking about life in general. He used to be in a heavy metal band; now, he’s married with a toddler. He tells me that so much of his life is about this balance he’s striving for. He wants to accomplish great things, something that will benefit humanity and leave his mark on the world. That takes time and a deep concentration bordering on mania. But he also wants to spend quality time with his family. Nobody’s found an algorithm for that yet.

I explain that I feel the same way, that I have similar struggles. I rarely have the time to write all the things I most want to, and I don’t spend enough time with my family. We’re two strangers trying to make sense of this world, together. That’s what hotel bars are all about.

We go on like this for a while. After the bar closes, there’s talk of going somewhere for pancakes. But no, it’s late, and we both know we have obligations in the morning. We follow each other on social media but never communicate again.

I realize, of course, that these are not the connections in life that matter. Family matters. Close friends matter. The relationships that are deeper, more complicated. The people who know nearly all of your secrets and love you anyway. And I know that when you accomplish something in life, it’s not because you lied to strangers at a hotel bar. It’s usually because you worked toward a goal—often longer and more intensely than you initially imagined possible.

Still, the anonymity of a hotel bar is alluring, intoxicating. There’s something compelling about stories from the life of a stranger: the desperate man fighting a silent phone, the barback with a broken heart, the woman who sells fantasies, the man who ponders the future for a living.

Then there’s the worst part of a hotel bar: the moment you pay your tab, get up from your stool, and return to real life.