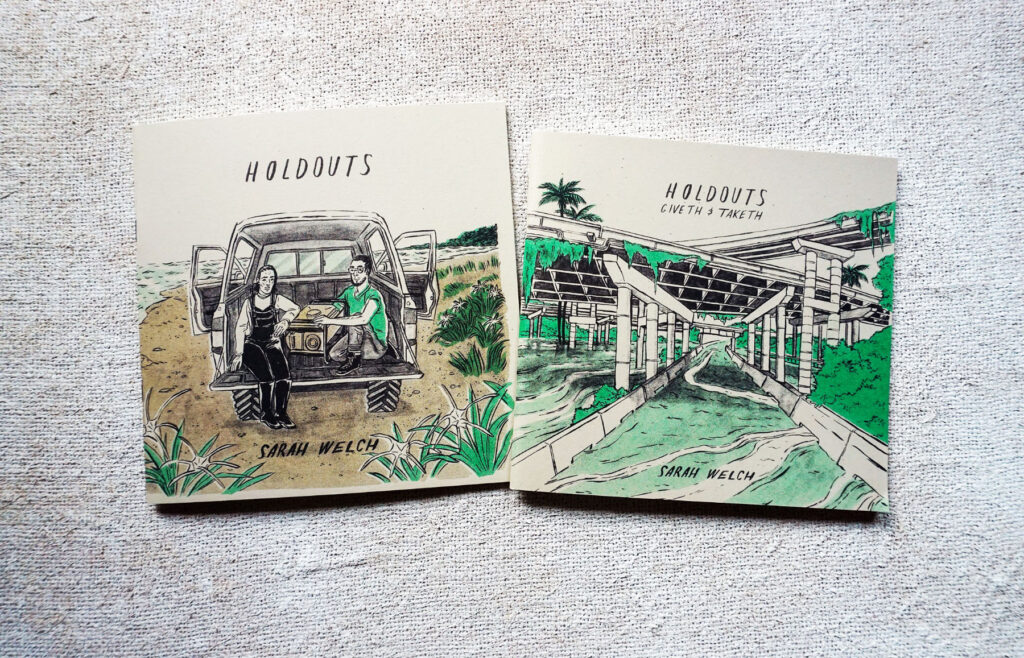

Sarah Welch’s Holdouts and Holdouts: Giveth and Taketh are featured in the exhibit Copy Culture. Courtesy of the artist.

Remember zines, those self-published, photocopied mini-magazines that proliferated among Generation X youth? During their heyday, these periodically produced journals informed readers what was and wasn’t punk in the ’80s and where you could skate and see underground concerts.

The movement seemed to crest in the ’90s, riding along a premium coffee-fueled tsunami that included grunge music, flannel shirts, and Third Wave feminism as exemplified by the Riot Grrrl movement. Looking back, I am a bit astonished there was never a movie starring Winona Ryder as a feisty and soulful zinester.

For the casual observer (namely, me), it had long seemed that zines, alongside record stores and bookshops, were yet another casualty of the internet. This notion was confirmed to me back around 2002, when I was music editor for the Houston Press, the Bayou City’s alternative weekly. I had the bright idea to write a story on Houston’s music zine scene, and found out it no longer existed. The entire movement had migrated to the internet, where anyone could write fired-up, raging blogs or cringeworthy self-confessional LiveJournal entries. It seemed, for a time, zines all but disappeared.

But zines have come roaring back. Cities around Texas, including San Antonio, Austin, and Fort Worth, are not just home to a few scattered zines, but fertile enough to spawn yearly festivals and other events. Beginning Saturday, Houston kicks off its own zine season, with two complementary and intertwined events: the opening of Copy Culture: Zines Made and Shared at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, and the release party of Homecoming, Zine Fest Houston’s 2021 anthology of Bayou City zines, occurring later that same day at Axelrad Beer Garden. Then, on Nov. 13, there’s a festivals devoted to zines at Zine Fest Houston.

Apparently instead of the internet destroying the movement, it has been made the movement’s servant, bolstering communities instead of wiping them out. Counterintuitively, many believe the rise of social media kickstarted the rebirth of zines.

“When social media started to become so in-your-face, people again started to want a tangible product, something they could connect with in a very tactile way,” says Anastasia Kirages, community organizer at Zine Fest Houston.

This leads to the question of what is and isn’t a zine. First, its creator must embrace the term, and the publication must be DIY. They are not subject to editorial oversight. After that, the parameters become harder to pin down, but generally speaking, they are targeted at a niche audience and are labors of love rather than moneymakers.

Some trace their history back to aficionados of Depression-era American science fiction, while others claim Thomas Paine’s Common Sense pamphlet published in 1776 was a hugely popular, world-altering zine.

Homecoming, Zine Fest Houston’s 2021 Compilation

“That was definitely an early zine,” says Houston Center for Contemporary Craft Curatorial Fellow María-Elisa Heg. “I even sometimes say Martin Luther’s 99 Theses was the first zine. Historically, I think the argument that self-publishing and self-control of the distribution of writing and other material has probably been ongoing since printing processes were developed.”

By definition, zines have always been oriented toward people on the margins, or who otherwise can’t get their voices heard. There can be, and often is, an anti-authoritarian element to them—they can be directed at the powers that be in city hall, the state capital, and Washington, or the moguls who run the music business or publishing industry. They can be as localized as high school, as was the case with two friends of mine who published zines that got them expelled from their high schools, and in one of those cases, even more trouble.

Andy Feehan, a Houston-bred artist long since an expat in France, was a pseudonymous contributor to an underground zine at the Bayou City’s Lamar High School in the late 1960s. It was called Reality, and Feehan cringes now at his nom de plume, the “Chicago Bluesman.”

“OK, OK, I was in high school—that’s my excuse. It was particularly ridiculous since there were no Black students at Lamar,” he recalls. Feehan says that he and his co-editor Bob Cash, now a labor organizer in Austin, wrote about Vietnam, racism, and police violence, “the usual lefty stuff.” For his troubles, not only was he expelled, but he had earned the attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s minions. “The FBI also took my picture,” he says.

But zines are neither limited to rebels nor those who choose counterculture. They also arise from those considered outsiders, such as people who identify as queer and zinesters of color, which is the focus of Copy Culture. Heg cites Shotgun Seamstress, an early 2000s zine she is spotlighting at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, as an example of a zine created by and for Black, brown, and queer fans of the punk scene. (Its editor, Osa Atoe, describes it as arising from “the experience of being the only Black kid at the punk show.”)

“They were really struggling on both coasts to [feel like they were welcome], and I know anecdotally that was the case [for marginalized people] in the ’80s and the ’90s, too. And so, it’s ongoing,” Heg says. “But I think in that way that we are reaching this intersectional inflection point to say…here’s a fuller picture of everybody who was involved in what they were doing then and now.”

Alternately, zines can be quirkily mainstream. Case in point, hey everybody… Let’s make a Zine!. Co-edited with his 18-year-old son, this zine is the brainchild of Patrick Brooks, a 50-something retired IT guy from Houston. The family-friendly hey everybody welcomes submissions ranging from recipes to poetry, essays to visual art, and is targeted at everyone from children to seniors.

To Brooks, a zine’s subject matter is limitless. It’s the spirit that counts, he says, and quotes legendary Nashville songwriter Harlan Howard’s definition of country music: Zines, Brooks says, are “three chords and the truth.”

Brooks is thankful for the resurgence of the form. “I never had the follow-through to complete any zines when I was a young punk,” he says. “But when I was in my early 50s, I guess I was ready to do so.”

No matter the content of your zine, just by putting one out there makes a statement, Kirages says. “Simply the act of self-publishing is very radical in itself. No matter if the subject matter is just a hobby or something like that, it’s still very radical to make the thing and then put it into the world. All you need is very minimal supplies, and you’re creating something that wasn’t there before.”

Copy Culture: Zines Made and Shared runs Oct. 2-Jan. 8 at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Related events include Copy Fest Zine Market and Demo with illustrator and comics artist Sarah Welch on Oct. 9; and Hands on Houston to Go: Zines 101 (a giveaway of zine-making kits) along with a zine-making demo by Anastasia Kirages, both on Nov. 6. Zine Fest Houston takes place Nov. 13 at the Orange Show Center for Visionary Art.

A previous version of the article had Shotgun Seamstress editor Osa Atoe’s last name spelled as Otoe. The spelling has been corrected in the article. Texas Highways sincerely regrets the error.