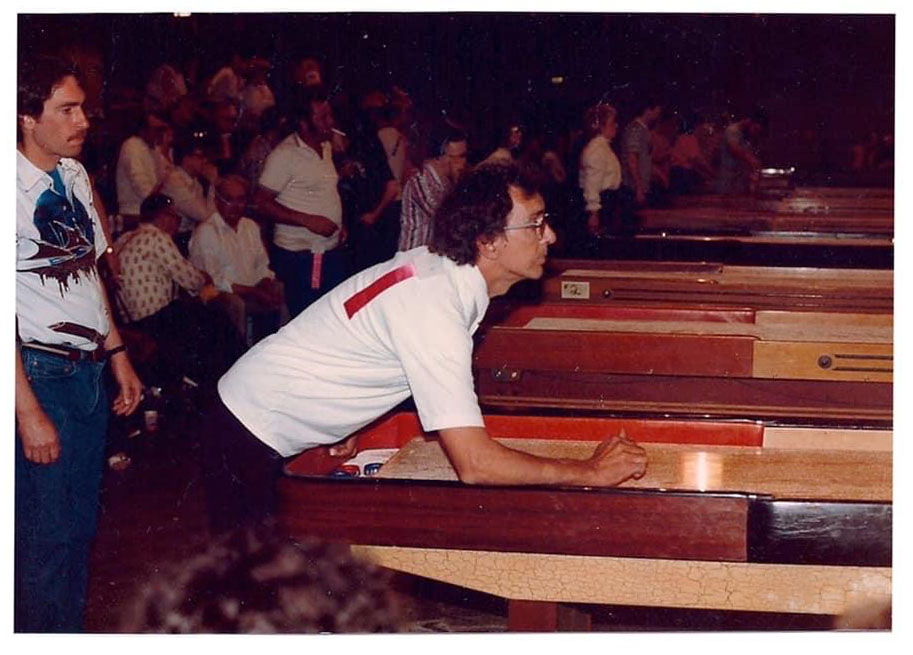

Photo of Billy Mays courtesy Brenda Mays Bishop

Billy Mays would lean over his end of the shuffleboard table and pick up a metal-and-plastic puck. With one fluid motion, he’d straighten his back, lift his head, narrow his eyes to make out the entire 22-foot-long table before him, then leaning forward, extend his arm to release his grip on the puck—sending it sliding gently, slowly, and exactly where he wanted it to go across the polished maple wood surface. That precision made Mays the best to ever play the game. A legend in his own time. The GOAT, to use sports fan parlance for “greatest of all time.”

“Whoever thought you’d be famous for playing shuffleboard?” says Carlton Stowers, a former Dallas sportswriter and author of 50 books about Texas. Having profiled Mays twice in the 2000s (well past his best playing days), Stowers remembers how Mays still shot the hell out of shuffleboard. “He found something he was damn good at, and my impression is that he liked his legend.”

That legend began with Mays’ birth in 1936 in Emory, 75 miles east of Dallas, where he first played shuffleboard at the age of 21. At midcentury, table shuffleboard (as opposed to the floor, or ship-deck variety) was very popular throughout the country, including Texas. As unlikely as this sounds today, shuffleboard became a way of life—at least for an exceptionally small number of people—and the man called “Texas Billy” was among them.

Shuffleboard, Anyone?

National Table Shuffleboard Day is Sept. 17. For the uninitiated, the game is played with one player against another or two teams of two players. Players alternate sliding (“shooting” or “lagging”) pucks (also called “weights”) across the table to either come to rest in a designated point-scoring zone, to block other pucks, or to knock other pucks off the board. First to 15 points wins. Up for a game? Here are places—recommended by Texas shuffleboard pros—to lag some weights.

Dallas

Island Club

10834 Ferguson Road

Hurst

Volcano’s Sports Bar

129 E. Harwood Road

San Antonio

Rookies Too

9200 Broadway St.

Houston

BIGgles Lounge Sports Cafe and Players Lounge

6150 Wilcrest Drive

Cedar Park

The Post Tavern

601 W. Whitestone Blvd.

Shuffleboard tournaments were held in Dallas and Houston and Mays just started winning them all. With confidence, he took his game on the road, playing shuffleboard in roadhouses, taverns, and dives, as long as games were for money, which financed his nomadic lifestyle. Mays made headlines coast to coast by showing up for, and often winning, local shuffleboard tournaments while he was also cashing in—using his arsenal of trick shots—against everyday players in small out-of-the-way towns, where the bets ranged from $5 to $500 a game.

In 1967, Sports Illustrated printed a 5,976-word feature, “The Hustle of Billy Mays,” that revealed his elite-level shuffleboard philosophy and his playbook for winning money from less-experienced players (which was everyone else). Mays crowed that he “hadn’t lost to a single player in the last five years” in the story, and then wearily admitted, “You get tired of being the best. I’m going to retire at 35—retire from playing and working.”

He didn’t. He won a ton of games, tournaments, and money for nearly five more decades. Former top-ranked player John McDermott met Mays in 1984 at a tournament in Detroit. “Billy was always the biggest name in the game of shuffleboard. He was the greatest player who ever lived. He played the game on a different universe,” says McDermott, who owns a shuffleboard manufacturing and distributing company in Michigan named the Shuffleboard Federation. “It was easy for road players to fly under the radar back then. Outside of Billy, who was an obvious legend and well known nationally, most of the rest of the great road players existed in relative anonymity.”

“He lived the game 24 hours a day for many years on the road at a time,” says Mahlon Nobles, a Houston-based shuffleboard pro, who met Mays 30 years ago in Dallas. Back then, he says, Mays played aggressively with chess-like deception, always outthinking his opponent by a couple shots. “He’d set you up in traps and then make a spectacular shot to get out of it.”

The Table Shuffleboard Association’s San Antonio director, Debbie Sexton, first saw Mays perform trick shots in the early 2000s. “I was a new player at the time,” she says. “When Billy walked in to play, it was like a celebrity joined us. Everyone knew him and were happy to see him, but they also checked their wallets because the hustler was there.”

Winning tournaments into his final years, Mays also performed trick shots at exhibitions, played pitchman for shuffleboard companies, and likely hustled up more than a few cash games on the road until his death in Dallas in 2015 at the age of 78. It was the end of an era.

The shuffleboard hustle is officially over, and Nobles doubts there’s ever really been anyone legitimately better than Mays. “Shuffleboard was a big con game. People actually made a living at it. Billy Mays was probably one of the biggest hustlers there was,” he says with admiration.

Billy Mays continued to win tournaments up to his death in 2015. Photo courtesy Brenda Mays Bishop.

Brenda Mays Bishop, Mays’ daughter who lives in Katy, remembers growing up and watching her father build and refinish shuffleboards in between road trips. His love for the game was deep because, “he was so good at it and because he wanted shuffleboard to thrive,” she says. “His colleagues praised him for teaching shuffleboard to anyone who wanted to learn.” (In 2009 the Table Shuffleboard Association inducted Mays into its Hall of Fame as both a “Player” and “Promoter” of shuffleboard.)

Mays’ legend continues to be robust. Robert Hoffman, a Dallas attorney and player who often lost $20 a game to Mays during his shuffleboard apprenticeship, says that in the right places (that is, places with shuffleboard leagues) “Texas Billy” Mays is still remembered fondly, even when they don’t know the whole story. “Some people forget that he had bad eyes. He couldn’t hardly see the far end of the table,” he says, explaining how a childhood injury and a boxing match forced Mays to wear thick glasses, like Coke bottles. “How could he be that good? He was a conundrum. He was an interesting guy. I liked him.”