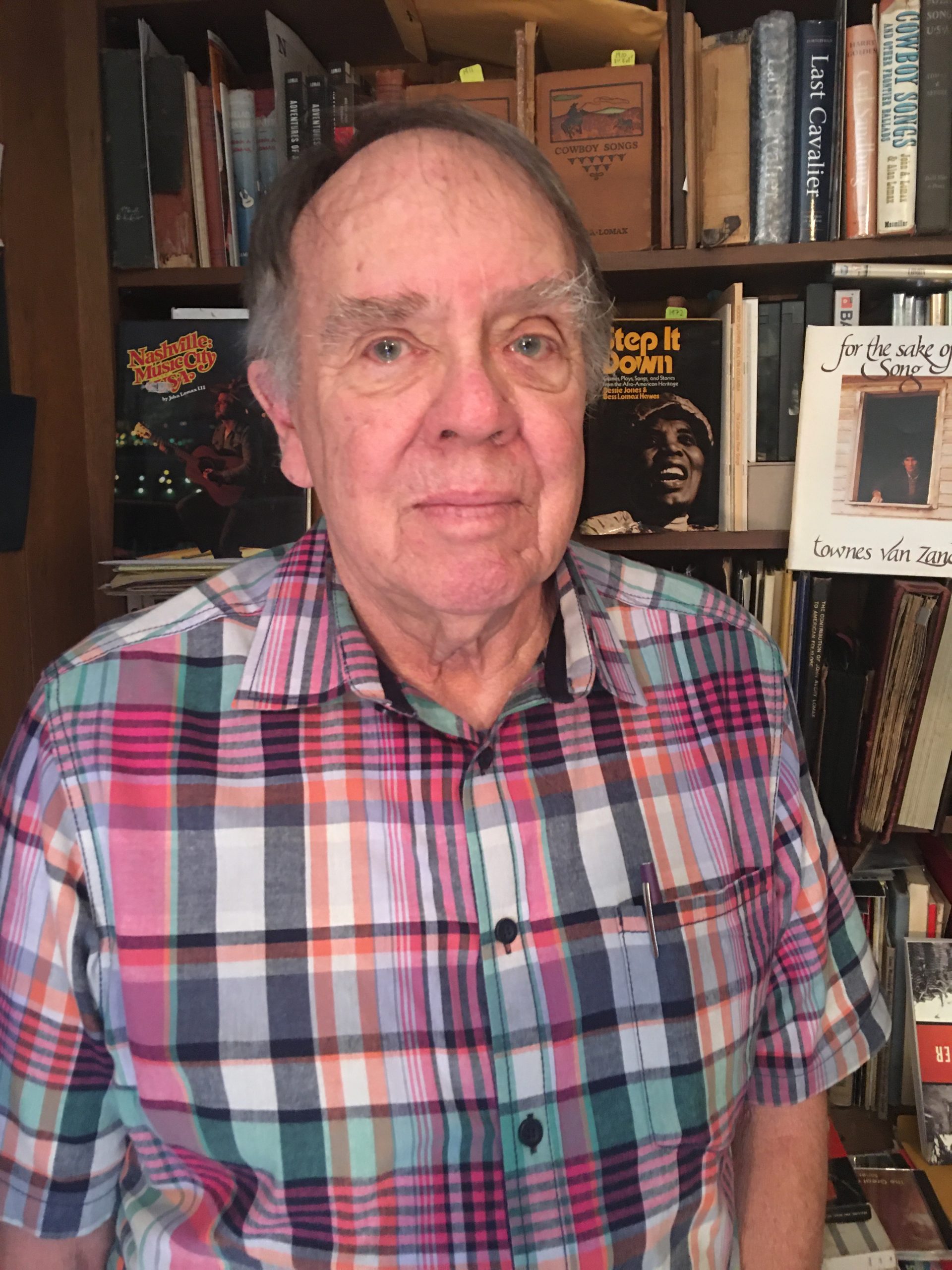

John Lomax III photo by Amanda Lomax.

John Lomax III has been part of my music life for half a century. We were both budding music journalists for Country Music magazine back in the 1970s, and he’s one of those displaced Texans I’d see whenever I visited Nashville over the decades. Every time, it seemed, he was into something new and cool: seguing from writing to managing artists like Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, David Olney, The Cactus Brothers, Kasey Chambers, and dulcimer player David Schnaufer (“He reinvented the instrument much as Earl Scruggs did for banjo,” John III says); hanging out with terrific Texas singer-songwriters like Guy Clark and Nanci Griffith; doing licensing deals; overseeing reissues; running an export record enterprise; teaching at Middle Tennessee State University.

Over all that time, I’ve never asked much about his family legacy, thinking John would probably be tired of the subject, since he was the grandson, son, nephew, and father in the first family of American music folklore. It was a surprise, then, to hear John Lomax III tell me in his thick, distinctive drawl that he made his debut performing in front of a live audience at the age of 77, singing songs and telling stories about the Lomaxes at a house concert near Nashville last month.

“Can’t sing for beans, but it’s not about the singer,” he admits from the start. “It’s about the songs and the heritage of our shared culture.” That translated into 19 songs and numerous stories over 85 minutes, performed in front of 20 people. “Seventeen of them strangers,” Lomax points out.

Now, with an Aug. 18 booking at Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas, as opening act for Michael Martin Murphey, and two October dates confirmed for Houston, the “Lomax On Lomax Show” appears to have legs. John III is learning more songs that were documented by elder Lomaxes and polishing stories about his family, who emigrated to Texas from Mississippi by covered wagon in 1869 and settled on a small farm in the Bosque River valley near Meridian that backed up to the Chisholm Trail during the era of cattle drives. Proximity to cowboys and a good ear were all the first John Lomax needed.

“Grandfather would hear the cowboys singing at night to keep the cattle calm,” John III recounts. “He started sliding out of the house to hear the songs better, somehow worked out a way to remember the melodies without musical training or books, and wrote down the words.” Putting to paper what he heard was the birth of the academic disciplines of ethnomusicology and folklore.

“My grandfather chased cowboy songs, riding on horseback with a tape machine tied to the front and back,” John III says. “He collected a lot along the Brazos. Grandfather’s father was a tanner. He described them as ’the upper crust of poor white trash’ in Adventures of a Ballad Hunter, John Avery’s 1947 autobiography, reissued in 2017 by University of Texas Press. A Black farmhand taught John Avery a whole lot about Black music.

“From there, the story goes to Alan, Bess, my dad, my brother, Joe (who published For the Sake of the Song: The Townes Van Zandt Song book), and me; and now a fourth-generation Lomax, John Nova, with his work at the Houston Press, Texas Monthly, and Texas Highways, where he is a writer-at-large.”

The 17,000-plus field recordings John III’s grandfather and his uncle Alan made for the Library of Congress are the gold standards of American music, capturing the diversity of songs and music makers across the United States before recording became commonplace. John Sr. discovered the musician Huddie Ledbetter, known as Leadbelly, and helped secure his release from Angola prison in Louisiana to launch his performing career, becoming one of the first artist managers some 90 years ago. Alan is credited with championing blues artists Robert Johnson and Mississippi Fred McDowell among others and was the first to record Muddy Waters. He befriended folk singers Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Burl Ives as well.

John III’s father, John A. Lomax Jr., sang folk songs, co-founded the Houston Folklore & Music Society, and managed blues giant Lightnin’ Hopkins, among other achievements. John III left Houston in 1973 for Nashville and a gig as publicist for storied producer and wildman Jack “Cowboy” Clement. Forty-nine years later, he has returned to Houston for an extended stay.

Coinciding with his performing dates at Rice University on Oct. 6, and for the Houston Folklore & Music Society on Oct. 8, John III is aiming to release a second, limited-edition vinyl-only album. The album will feature recordings his father made from recently discovered Peter Gardner tape reels of Houston Folklore programs and other events from the mid-’60s.

“Peter would have people come over to his house and sit around and sing, and it would go out over the air on the radio,” John III says. “It’s impressive how many people got their start at Houston Folklore: Guy Clark, Nanci, and Townes, Lucinda [Williams], Steve Earle, Richard Dobson, and KT Oslin. Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb were regular Folklore Society performers.”

While John III’s father and late brother Joe were both recognized folk singers, John III comes late to the game—but he’s fully aware of his role. After his export record enterprise “got eaten by streaming,” he started looking for something else to do. “I’m the last male left from that generation to get out there and do this—keep the songs alive, keep the legend alive, embellish the brand,” he says. “I got to trying to sing, putting on headphones, listening to my dad, singing along with him to get the timing.”

Like his father and grandfather, he sings a cappella. He first performed publicly five years ago when he put out FOLK, an album of 16 of his dad’s home recordings. “I did a few things to flog it and got on Michael Johnathon’s WoodSongs Old Time Radio Hour on their anniversary show—me and Roger McGuinn,” he says. “I knew one song, ‘Buffalo Skinners.’”

His song list has grown considerably. “It’s come really easy,” he says. “I’ve heard these songs all my life. It’s all about the song. It’s about the stories of this one family, how we started, how we’re still at it 100 and some odd years later.”

For the format of the “Lomax on Lomax Show,” John III keeps it simple, starting off with cowboy songs. “‘Home on the Range’ was first published in a book by my grandfather in 1910,” he says. “I sing that but skip the verse everyone knows and do two or three verses that are rarely heard. They’re just as nice and pretty as the standard old ‘deer and the antelope play.’”

He then segues into Leadbelly, which leads to his uncle Alan. “[He] was the first to record ‘Sloop John B’ in 1935 in Nassau [Bahamas],” John III says about the song that became best known for the Beach Boys version. “Then I sing some songs my dad used to sing, then a Townes song, ‘Two Girls,’ because there’s a funny Doug Sahm story to it, and ‘My Old Friend The Blues,’ one of Steve Earle’s underappreciated gems. I close with this incredible song Ed McCurdy wrote in 1950 that’s on the second album of my dad’s recordings from 1965, ‘Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream.’”

In between he summons up obscurities such as “The Frozen Logger,” which was recorded by Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley, and Leadbelly’s “Roosters Crows at Midnight.” He’s also working out “Chisholm Trail.” “It’s not very obscure, but, really, the whole thing is obscure to the general public,” he says. “People in the business know some of these songs. The ‘Ballad of the Boll Weevil’ and ‘Sloop John B’ are the only two songs I do that were big hits, but that was nearly 60 years ago. … I want to keep these songs alive, because they’re so cool. This is America. Come on, let’s keep this thing going, folks.”

Songs uncovered by the Lomaxes continue to resonate in modern music, often through sampling. For instance, “Rosie,” which Alan Lomax recorded at the Mississippi State Penitentiary (also known as Parchman Farm prison) in 1947 and released on the album Prison Songs: Historical Recordings from Parchman Farm 1947-48 Vol. 1: Murderous Home, was sampled on the 2015 song “Hey Mama,” a massive hit by David Guetta that featured Nicki Minaj, Bebe Rexha, and Afrojack.

“That has actually generated more income than any song in the whole Lomax canon, more than Leadbelly’s ‘Midnight Special’ or ‘Goodnight Irene,’” John III says. “It was a hit in 18 countries.”

And on her 2016 song “Freedom,” with Kendrick Lamar, Beyonce sampled “Stewball,” sung by Prisoner 22 and recorded by Alan Lomax and his father at Parchman Farm in 1947. The phrase the song draws its title from can be found in “Collection Speech/Unidentified Lining Hymn,” performed by Reverend R.C. Crenshaw and recorded by Alan Lomax in 1959.

The more John III talks about the family legacy, the more the pride comes through. “You’ve got this one family now in its fourth generation steadily helping to preserve, promote, publicize, and otherwise draw attention to these wonderful songs, the people who created them, the people who sang them,” he says. “It’s something no one is really doing.”