I was far from home to begin with.

I live 4,900 miles away from England, where I was born, on any day of the week. But on that day, home was getting farther away still. It’s not just the eight-hour drive with my family from Austin, where we now live, to Terlingua. It’s something else, something farther than the distance … everything is left behind en route.

Increasingly, you put away all thought of every other place as this new place comes closer; it’s as if you’re falling off the map. There are fewer and fewer human beings as the land takes over. The closest I ever came to feeling this remote before was venturing into the Scottish Highlands, where I believed we’d at last reached the end of mankind and nature had finally won. It wasn’t a bad feeling at all. Only there, everything was much greener.

Here, once upon a time, was home to 2,000 people, but no longer.

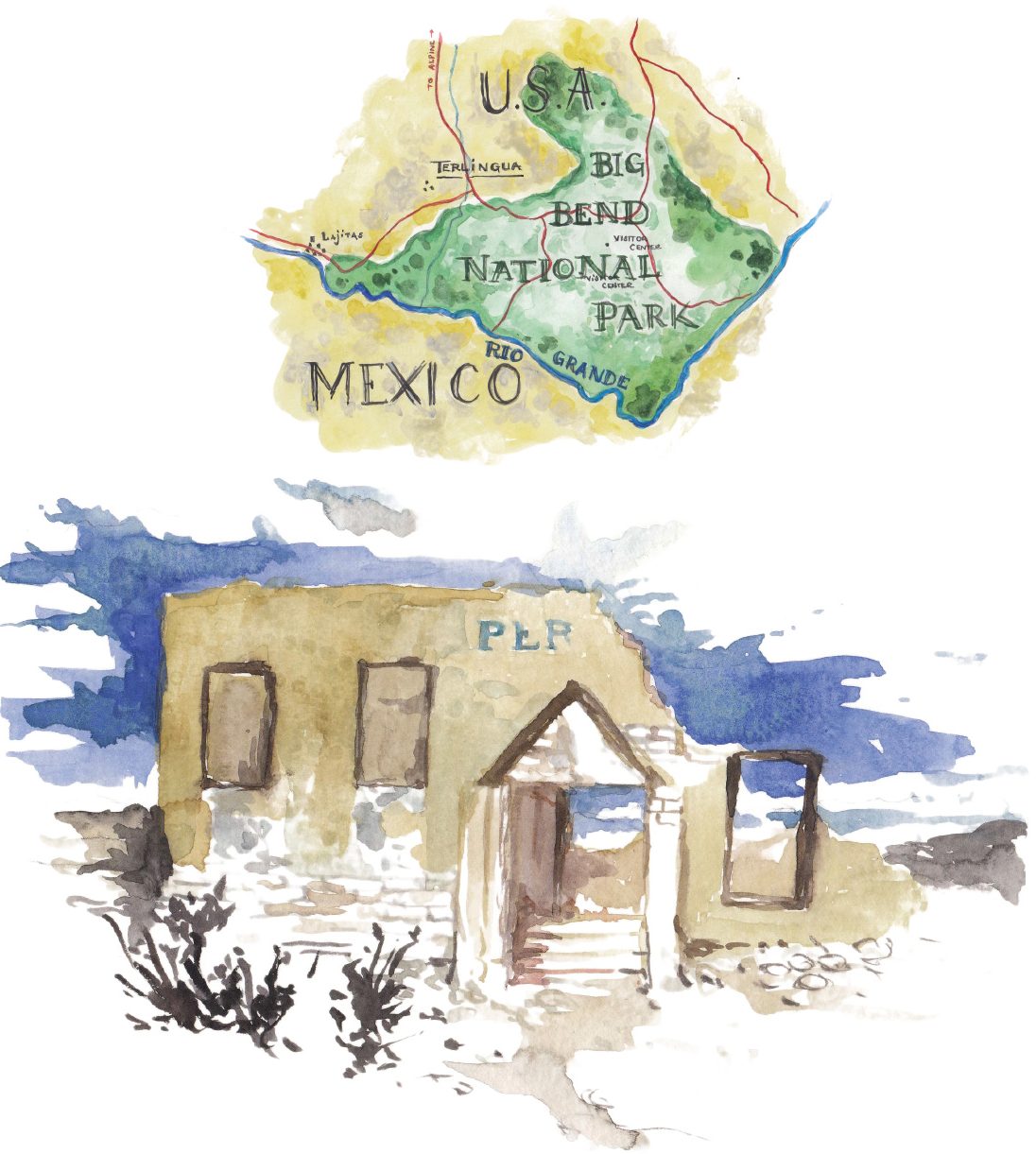

The roads to Terlingua get smaller as you get closer—first Interstate 10, then US 90, then onto the quieter State Highway 118, and finally FM 170 toward Lajitas; the farther you are from “neighboring” Alpine, the closer you are to nowhere. And then at long last you arrive, up a small dirt channel to Terlingua, a ghost town. “We’re here,” my wife and I tell the kids.

Here, once upon a time, was home to 2,000 people, but no longer. Staying in Terlingua is like visiting the history of humanity abridged—once upon a time, it seems to say, there was a species called human. You can feel the past. My children, 9 and 11 years old, love the past. One of their favorite occupations on holiday in London is to go mudlarking through the debris the Thames throws up on its foreshore at low tide. There they gather animal teeth, bones, clay pipes. Here was the past again, proof of humans gone before us. Houses without roofs, missing walls, but the outlines of each dwelling are clear enough. Here were humans. But here are skies, living, ever-changing, enormous skies. Like a J.M.W. Turner painting, the humans take up the smallest part of the canvas. We had come to stay for a few nights, sleeping in the former mine manager’s cottage.

Terlingua came into existence in 1903 after the Chisos Mining Company discovered cinnabar—the ore containing mercury—in the ground. A mine was begun, and the town formed around it. The demand for mercury increased with the advent of World War I because it was used in munitions.

This cottage, so we were informed, was the first building to come back after Terlingua had been abandoned in the 1940s. After the humans turned their back upon it, nature seized what was once hers. But, starting with this building in the 1970s, Terlingua had begun to haul itself back to life.

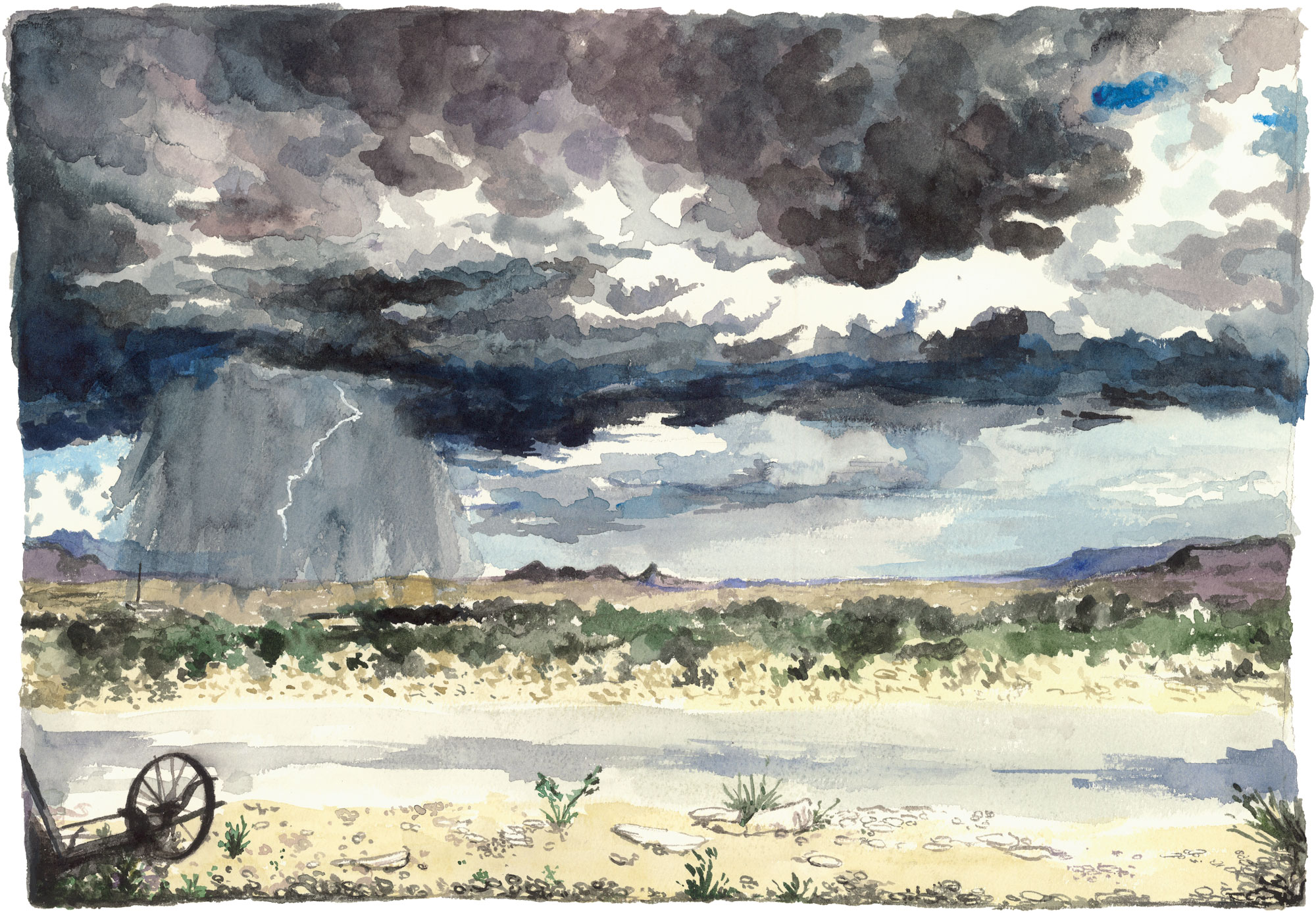

A storm lit up the sky our first night in Terlingua. Its approach was evident three quarters of an hour before it finally arrived. The kaleidoscope of colors—bright blues and battleship grays, blacks, purples, reds, and yellows—came ever closer, whistling and humming, drumming, rolling, closer and closer, darkening. What a display of light. We sat on the cottage porch; we’d not seen a storm quite like this before, as if nature was showing off. It no longer resembled Turner, but more like those drawings by Leonardo da Vinci of a deluge. That was our first night: nature proclaiming itself.

The next morning, small traces of the storm pooled in the streets of the old town, but nature calmed as I set out to meet Terlingua one on one. I am a writer and illustrator of gloomy novels set in dilapidated palaces and amongst monumental dirt heaps where objects can speak. I wondered what on earth I would find in Terlingua and how it would feel to be in a ghost town.

But I was never alone for very long, as I went out to meet the town. A few steps into my early-morning stroll, a baby rabbit hopped very close, just 2 feet away, and we looked at each other for a little while. Farther down the track is the Perry Mansion, where Howard Perry, owner of the Chisos Mine, built the town’s largest structure in 1909. The mansion is no grand, elegant piece of architecture but rather an oblong of rock and adobe perched uphill from much of Terlingua, whereupon it announces its dominance upon the less preserved buildings that surround it. It looked to me a strangely bisected property, missing its other half, or a part of a film set. But its solid presence provides legible history to the surrounding rubble of the town. The mansion is being converted into tourist lodgings. Terlingua is ever more populated—a fact the residents are not always pleased about.

Is it a place between the living and the dead?

Just in front of the Perry Mansion, I came upon a worm, larger than any I had met before. Its presence spoke of strange things to be found under the ground. It told me I knew very little of the nature of this place. Across a ravine, I saw the old school house, where once upon a time 80 children had been educated. I saw St. Agnes Church, its windows and doors wide open, and stepping inside and approaching the altar, I thought I was alone there. But as I reached the altar, a hundred darting birds flew out; some escaped through the windows, but many stayed around. Here was more life. I began to feel the size of Terlingua, past and present, living and dead.

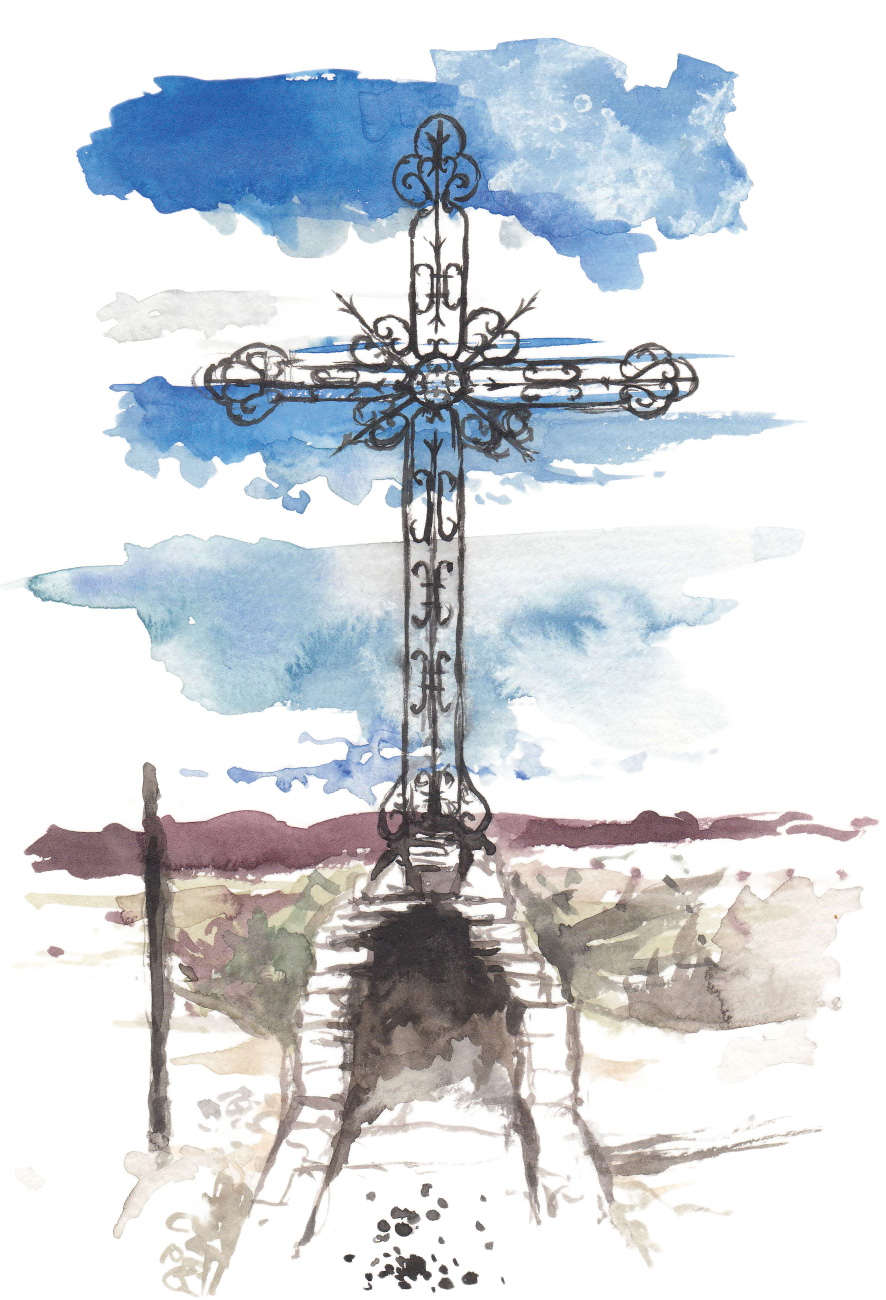

I have not known many ghost towns. I remember a small village that had been wiped out by the Black Death that was up the hill from the village where I grew up in eastern England, and I would putter through it with our dogs, stumbling inside the apse of the church that had not been worshipped in for hundreds of years. I have been to a certain coal-mining town in Pennsylvania that has been labeled a place of high toxicity after a vein of coal had caught fire deep underground; there the graveyard had miraculously escaped the destruction. There’s a graveyard in Terlingua, too, and in it rest over 400 souls.

It is important to point out that Chisos records don’t link any deaths to mercury poisoning. It was influenza that had mostly stopped them. Important, too, to state that this is no closed cemetery, filled up with its dead and no longer open for business. There are new graves here; the dead are still being collected because Terlingua has occupants once more. But it is not only that: I never saw the graveyard without a handful of visitors, both tourists and locals, meandering through it. From the graveyard you can look back up at the town and see its living.

Remember, these people don’t want to be found, I was told.

There’s the Terlingua Trading Company, the most notable building, where sitting with a beer on the front porch, you can contemplate the universe whilst taking in the most astounding view of the Chisos Mountains. The porch is the central social scene of the whole town, so it’s also a good spot for conversing with the locals. Next door is the Starlight Theatre, a former cinema, now an excellent restaurant, where you can eat chicken-fried boar strips among other wonders. Indeed, looking at Terlingua from its graveyard it’s hard not to notice how populated this ghost town has become. There are people to meet here, and they are not ghosts.

In the weeks before I came to Terlingua I struggled to make contact with its inhabitants. I was given a few leads and left phone messages and emails, but the response was always very quiet. “Remember, these people don’t want to be found,” I was told. I uncovered more leads and tried to get hold of Bill Ivey, the man who started to return Terlingua to the living, adding his own beating heart and that of his family to the ruins. He bought the whole town—the church, old mansion, theater, cemetery, all of it—in 1983 and slowly began the process of turning it into the very best place for people to stay when visiting Big Bend. He had a huge hand in making Terlingua a community again. To begin with, Ivey resurrected the mine manager’s cottage, where our family stayed during our visit, and there he lived for a while with his young family, joining the tiny community of Terlingua. But soon other people started coming back.

From the graveyard you can look back up at the town and see its living.

My main point of contact was Tony Drewry, who has been living in Terlingua for two years and is working on a book about his new home. We communicated over email, where he generously rolled out a whole dramatis personae of the new residents. Still, the residents remained rather aloof. I had a couple of contacts, though, and hoped I would find more after I arrived in Terlingua. I wondered if the populace would be confused by a diminutive Englishman come to wonder about their daily lives. I feared I would be intruding.

But, once there, once among them, the residents proved loquacious and happy to talk about their rather particular address. “I wanted to get away” was the most common observation. Being here you can see why people stay—

somehow all other life appears contrived after being in Terlingua, where you sit so nakedly amongst so much omnipresent nature. There are many tales of people born in this region, who for personal or economic reasons left, but returned to live here again. I suppose once it is under your skin it is impossible to shake off—nothing else would seem quite real enough. One old resident, who spent her life on the Rio Grande—just a handful of miles down the road—told me that she was always instructed when swimming in the river as a girl, “Don’t pee in it; you know you’ll be coming back.”

“Will it last?” I asked one native, who like the others, was very happy to talk with me in person but preferred to keep her name to herself. She’d been here, left, and returned again, and now made beautiful art of the ghost town around her. We bought a small painting of the Perry Mansion, captured with a broken roof, the sky looking into the building—painted before it was restored. There may come a sudden storm and wipe this whole place out again, and then, after a time, she supposed, slowly they’d trickle back again.

Somehow all other life appears contrived after being in Terlingua, where you sit so nakedly amongst so much omnipresent nature.

Perhaps for a little while, like the pigs in the fairytale, they’d build their home of straw and sticks and stone—and persist. Turn around, like a strange game of grandmother’s footsteps, and nature will take your place from you. She told me how quickly nature took back any abandoned building. But come here when the Terlingua International Chili Championship is on—and, poof, the humans are so many ants. The event, called the “granddaddy of all chili cookoffs,” is held on the first Saturday in November every year and some 10,000 people attend. I can’t imagine what Terlingua might look like with such a population. But that is only once a year.

Terlingua feels unspoilt and adventurous. Big Bend is on the doorstep; another country is just beyond. The world looks different from here. It is refreshing to look out and see only the smallest trickle of humanity, and beyond it, the lunar landscape. Is it a place between the living and the dead? It feels very alive but knows—and this seems to me its magic—that it hangs in the balance. The ruins of old Terlingua are all about, and they feel as if they are as factual as the ruins of the Ancient Egyptians: Here were humans. And here are humans again. What a place to be with nature and to feel it everywhere around you. To remind us that our lives are all improvised.

It is generally believed Terlingua is named, in a corrupted Spanish, after the three languages spoken by the Apache, Comanche and Shawnee tribes. There are others who think the name comes from an old Native American word, the meaning of which has been lost, and that feels somehow right. We left cleansed and fascinated, and moved and welcomed, by the beautiful town of Terlingua, with its living and with its dead. There are stickers about, and I echo them: Viva Terlingua.