Arborist Steve Houser examines the California Crossing tree, a pecan with a bent trunk that points to a low-water crossing in Dallas.

No historical marker indicates that this particular pecan tree near the grounds of the Texas National Guard Armory in northwest Dallas is special—just the fact that its trunk grows along the ground for about 25 feet before turning upward. Sometimes natural forces, such as ice storms, can bend trees into strange shapes like this. But for this pecan, its shape is no accident.

Steve Houser, a local arborist and founding member of the Texas Historic Tree Coalition, traces his fingers over scars on the tree’s trunk, signs indicating humans may have lashed down the trunk with yucca rope some 150 years ago, when it was a flexible sapling. The bent tree, known as the California Crossing marker tree, points to a low-water crossing on the Elm Fork of the Trinity River, offering valuable information to those who would have recognized it as a marker tree.

“The typical settler would go right by,” says Houser, chairman of the coalition’s Indian Marker Tree Committee. “A Comanche would see it and follow it. Trees told them where to go to.”

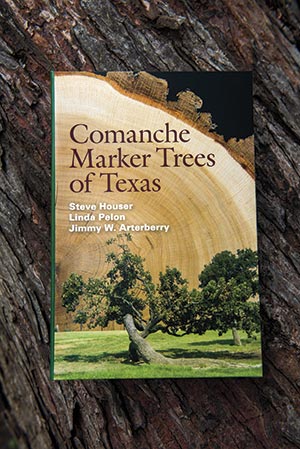

While the concept of Comanche marker trees is sometimes dismissed as ranch lore, Houser isn’t just blowing smoke. He has been studying marker trees for more than 20 years and last year released a book on the topic, Comanche Marker Trees of Texas, co-authored with Jimmy W. Arterberry, the Comanche Nation tribal administrator, and Linda Pelon, a Waco anthropologist. The book profiles six Dallas-area trees identified as marker trees, explores their history, and explains the Indian Marker Tree Committee’s process of researching and evaluating potential marker trees.

Some historians believe Comanches would shape trees to signal directions, leaving scars where they were altered and tied down.

With increased attention, Houser has received tips about hundreds of possible marker trees around Texas. He currently has files on 176 potential marker tree sites, nearly half of which have been ruled out. It’s not an easy test to pass.

“A lady sent me a tree with a 90-degree angle. It was only about 12 inches in diameter; I told her it probably was not old enough to be a marker tree,” Houser recalls. “She says, ‘Okay, I want a second opinion.’ So I say, ‘Okay. It’s pretty ugly, too.’ She laughed, but there’s no other opinion you can get.”

Comanche marker trees in Texas, typically native, long-lived species such as bur oaks or pecans, must be at least 150 years old, dating to the 19th century when Comanches lived and hunted here. Some historians believe Comanches would shape trees to signal directions, leaving scars where they were altered and tied down. Such trees, known as “turning” trees, often have sharp bends in their trunks.

Artifacts like arrowheads found nearby can bolster the case that a tree was a purposeful marker. But it’s even more important that the tree marks something that would have been important to Comanches traveling through the area, whether a natural spring, a high signaling point, or a low-water crossing. Trees that aren’t bent can also be marker trees for other purposes, such as a designated meeting place like Austin’s Treaty Oak.

Houser helped to form the Texas Historic Tree Coalition after a Dallas hospital offered him a job removing historic oak trees on its grounds. He opted instead to fight to save the trees, and his research led him to the topic of Indian marker trees. Houser says it can be tricky to figure out the purpose of potential marker trees more than a century after westward expansion displaced the Comanches from their former territory. “I start with early trail maps, spring maps, topographical maps,” he says.

Dallas arborist Steve Houser is co-author of “Comanche Marker Trees of Texas,” published by Texas A&M University Press in 2016.

When a tree meets all criteria, he forwards it to the Comanche Nation Tribal Council in Lawton, Oklahoma, for approval. So far, nine Texas trees have emerged from the lengthy process to be officially identified as Comanche marker trees, some on public land and others on private property. On several occasions, tribal elders have traveled from Oklahoma to confirm the trees’ historical significance. It’s been a joyful reunion, Arterberry says, although he was initially skeptical when he first encountered Houser and Pelon.

“People try to tell you about your culture from what they’ve read or studied; I’m not quick to agree about things,” Arterberry says. “When you see they’re serious about their quest, you give them a little more guidance. At some point they have a better understanding. At the end of the day because they’re not Comanches they’ll never fully get it, but they can get close.”

Houser understands the tribe’s reticence to share information with him. “You don’t blame them a bit if you know their history,” he says. “When they realized I’m a volunteer arborist and my only goal is to help them reconnect with their trees, they started to accept me.”

The most recent tree acknowledged by the Comanche tribe is in the town of Holliday, about 15 miles southwest of Wichita Falls. The 60-foot tall pecan tree grows parallel to the ground for a dozen feet near a creek at Stonewall Jackson Camp No. 249, also home to a United Confederate Veterans monument. The tree marks a nearby water source.

“I think the importance of it has to do with identifying the connection of Comanche culture to these different locations,” says Arterberry, who previously served as the tribal historic preservation officer. “It’s not only the history of Comanches, but also the history of Texas, of America.”

For his part, Houser is delving into additional research on bent trees and experimenting with lashing down saplings to see how they grow. “I’m trying to redo their methodology using yucca rope,” he says. In the office of his Wylie-based tree-care company, Arborilogical Services, he keeps batches of tree “cookies,” or slices of branches used to determine a tree’s age.

Other marker-tree clues are less tangible. “To a certain extent, I can sense the personality, the health of the tree, its condition,” Houser says. “Can I sense what’s a marker tree? Probably not. Some I thought were marker trees, the Comanches didn’t recognize. I think they have a better feel for the spiritual side of things. But sometimes there is a gut feeling that there’s something more to it.”

Comanche Marker Trees

The Texas Historic Tree Coalition Indian Marker Tree Committee has identified nine historic Comanche marker trees that have been officially recognized by the Comanche Nation. Some of the trees available for public view are:

1. The California Crossing tree is in a park next to the Texas National Guard Armory in Dallas, 1775 California Crossing Road.

2. The Bird’s Fort Trail tree is in Bird’s Fort Trail Park in Irving, 5756 Riverside Drive.

3. The Holliday tree is at Stonewall Jackson Camp No. 249, 2.5 miles south of Holliday on Farm-to-Market Road 368.

Houser continues to investigate reports of potential marker trees while also keeping an eye on the health of recognized trees. Time is an issue. While oak and pecan trees can live for hundreds of years, they also face manmade threats from development and vandalism and the natural threats of storms and drought. A pecan at Gateway Park in East Dallas—identified 20 years ago as a marker tree for a Comanche campground—fell victim to a storm in the late 1990s. A post oak known as the Irving Escarpment Ridge tree—which marked a paint-rock quarry in Comanche times—died in a drought in 2011. This past summer, the California Crossing tree lost one of its two upright limbs in a storm.

Just across the Dallas border in Irving, the Bird’s Fort Trail marker tree picks up the ancient trail signaled by the California Crossing tree on the other side of the Elm Fork. Located in Bird’s Fort Trail Park, not far from a tidy suburban picnic shelter, the bur oak grows along the ground for 15 feet before reaching up. But the tree appears to be failing, Houser says. He points out nearby road and building construction that may have damaged or covered the tree’s roots.

Even recognized marker trees aren’t afforded any special protection. “This is what underscores the need to find them before they’re gone,” Houser says.

The Texas Historic Tree Coalition Indian Marker Tree Committee accepts tips on possible marker trees. Email photos/inquiries to Steve Houser.