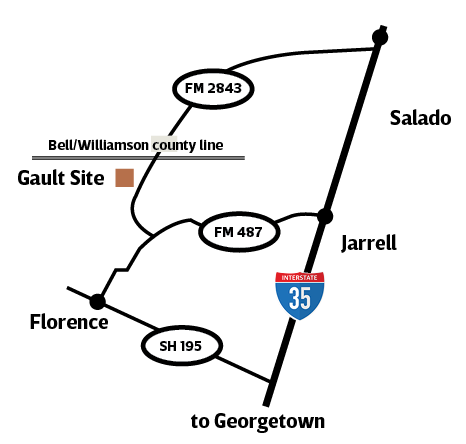

Heading west from Georgetown, away from the crowded Interstate 35 corridor, the countryside turns green with meadows and woodlands along State Highway 195. A water tower looms into view, announcing a town with unusually deep roots: “Florence: Est. 18,000 B.C.”

A few miles away, near Williamson County’s northern border, a rocky outcrop along the clear, spring-fed pools of Buttermilk Creek reveals the reason why people have been gathering in this place for thousands of years. The limestone wall is streaked by a seam of chert—a sedimentary stone used by North America’s earliest residents to make tools.

The perennial springs and abundant chert in this area—known by archeologists as the Gault Site—made an ideal setting for early humans, says Clark Wernecke, a research associate with the Gault School of Archaeological Research at the University of Texas. “This place was regularly occupied,” he says. “It was the right place with the right stuff. We tend to try to make them more primitive, but these were all people just like us.”

Numerous chert flakes—leftover debris from making stone tools—are scattered around the site. Even more clues lie beneath the soil in stratified layers, where archeologists have excavated millions of artifacts that indicate ancient hunter-gatherers were here 16,000 to 20,000 years ago. That makes it one of the oldest and most archeologically significant sites of human occupation in the Western Hemisphere. It’s a key piece of evidence for archeologists challenging the “Clovis First” theory, a long-held hypothesis that the first people in the Americas—the Clovis culture—crossed a land mass at the Bering Strait from Asia and migrated to points across North America 11,000 to 12,000 years ago.

“When you have a site like Gault, you have the ammunition that says you need to rethink things—and that’s powerful,” says Sergio Ayala, executive director of the Prehistory Research Project at the Gault School.

“It’s not a race to have the oldest thing, it’s a race to understand the human story better,” he adds. “Gault is helping archeologists understand the story of who the earliest humans were in North America, and when and why they arrived.”

The ancient pioneers at Gault hunted and butchered birds, frogs, turtles, small mammals, bison, and mammoth. They also harvested chert, which they broke and chipped—in a process known as flintknapping—into sharp-edged knives, points, scrapers, and other tools. And they kept returning for the reliable sources of water, food, and stone.

Archeologists believe people of the prehistoric Clovis culture occupied the Gault Site, in part because they’ve found Clovis artifacts, including distinctive fluted stone points. But stone tools predating the Clovis by thousands of years have also been discovered at Gault and other sites, presenting contradictions to the Clovis First theory.

The artifacts uncovered at Gault indicate “many different hunter-gatherer groups, not a single group or culture,” Ayala says.

Early artifacts also show the inhabitants incised some of their chert and limestone, scratching delicate fine lines, pyramids, and spirals. The incised stones are “the oldest art in the Americas so far,” Ayala says.

Archeologists have been studying the Gault Site for about 100 years. Named for Henry Gault, who bought the land outside Florence in 1904, the property remained in private hands until 15 years ago. In the 1930s, UT professor J.E. Pearce found numerous artifacts at the site and conducted field work. He also lamented the site was being “destroyed” by looters and people digging up specimens to sell. This continued into the 1980s and ’90s, as a former property owner allowed people to pay $25 a day to dig up artifacts to collect or sell on the antiquities market.

In 2007, Michael Collins, a UT archeologist, used his own money to acquire the site to preserve it. It was one of “the biggest nests of Clovis artifacts I’d ever seen,” he later recalled. “I was just flabbergasted.” Collins formed the nonprofit Gault School and donated the site to The Archaeological Conservancy. For the next decade, archeologists and volunteers from around the world excavated about 3% of the site and extracted 2.6 million artifacts. The excavation area has been mapped and filled in; today it looks like a grassy flood plain.

Now, the work has moved to the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at UT’s J.J. Pickle Research Campus. In a nondescript portable building, workers are curating the Gault collection—cataloging and organizing the artifacts and creating a vast digital analysis database for future researchers. Another important step will be the publication of the scientific monograph—a report describing the site, its findings, and its significance—by Texas A&M University Press.

Ayala says the scientists’ interest in the Gault Site is about more than the past.

“Archeologists are really interested in what that past can tell us about the future,” he says. “We’re interested in where man’s going. Where are we going as a species? Those groups were coming into a new land with a rapidly changing climate. What can we learn from them?”

More public exposure is on the way. Filmmaker Olive Talley, who previously was an investigative reporter and a producer on Dateline, is making a documentary about Gault. A resident of Dallas, she says her goal is to tell a story not only about science but also about the work of Collins and a team of volunteers.

Exploring Gault

The Gault School of Archaeological Research hopes to open the Gault Site to the public someday, but for now it’s only accessible through guided tours.

To schedule a tour with the Gault School of Archaeological Research in Austin, visit gaultschool.org.

At the Bell County Museum in Belton, the exhibit Gault Site: A Wealth of New Archaeological Evidence covers the site’s history and culture with murals, artifacts, and a film. 254-933-5243; bellcountymuseum.org

At The Williamson Museum in Georgetown, the Tech in Ancient Texas exhibit presents technology from flintknapping to contemporary imaging. 512-943-1670; williamsonmuseum.org

Monthly guided tours of the Gault Site are offered on alternating months by the Bell County Museum and The Williamson Museum. The tours start at 9 a.m. and last about three hours. Cost is $10 per person; children 10 and younger are free. Check with the museums for 2023 tour dates. Preregistration is required.

At the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin, the Becoming Texas: Our Story Begins Here exhibit includes a Gault projectile point. thestoryoftexas.com

Learn more about Olive Talley’s documentary about the Gault Site at gaultfilm.com.

“As our ancestors go farther and farther back, it just makes you wonder,” Talley says. “We know from archeology and anthropology a lot about ancestry in Africa. We know a lot about ancestry in Europe and other continents. We’re still learning so much about ancestry in North America.”

She hopes to have a rough cut of her yet-to-be-titled film completed by early 2023 and to premiere it by the end of the year. “To me it’s this human story that’s so compelling,” Talley says. “It’s still a wonderful mystery. This is a treasure in our backyard.”