Old Tunnel State Park sits on a brush-covered limestone ridge that divides the watersheds of the Guadalupe and Pedernales rivers, about halfway between Fredericksburg and Comfort. With only 16 acres and three picnic tables, the park is the smallest in the state system. Every evening from May through October, visitors perch on low wooden bleachers to watch 3 million Mexican free-tailed and cave myotis bats swarm out of the abandoned railroad tunnel, spiraling into the dusk above hills that march toward the horizon.

Near the bleachers, an unpaved trail descends a hillside to the tunnel entrance, which looks like an ancient crypt in the limestone cliff. A sign warns visitors to stay out of the tunnel, but given the bat guano piled in the damp darkness, warnings probably aren’t necessary. The tunnel recalls a time before railroads and highways sliced up the Hill Country. Until laborers hammered and blasted their way through 300 yards of limestone to build the tunnel in 1913, the people of Fredericksburg relied on ox-drawn freight wagons to deliver goods to and from San Antonio, a week’s travel away. But times were changing fast.

“The railroad was the first true physical modernization of Fredericksburg,” says Lacey LeBleu, a curator at the Gillespie County Historical Society. “It really connected the town to the larger world and was the first glimpse of not being so isolated. It brought Fredericksburg a little closer to the modern era and made it easier to bring in modern farming equipment, not to mention oil and gas.”

As railroads stitched their way across Texas during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Fredericksburg’s detachment nagged at civic leaders of the town, among the largest in the Hill Country. To do anything about it, however, railroad proponents had to get through that imposing limestone ridge known as the “Big Hill.” Fredericksburg’s campaign for rail began in the early 1880s. Local officials formed a committee to raise money and lobby railroad companies, says Hugh Hemphill, historian for the Texas Transportation Museum in San Antonio.

In 1886, the San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railway announced its plan to build a line into the Hill Country. Fredericksburg bid for inclusion, but after laying tracks to Comfort, just 20 miles south of Fredericksburg, the route instead veered west to Kerrville. Charles Schreiner, the influential merchant and owner of YO Ranch in Kerrville, lobbied for his town, noting how difficult it would be to solve the problem of the Big Hill, according to an article by the late historian C.F. Eckhardt.

As it happened, just the year before, an unlikely person rolled into Fredericksburg—Temple Smith, a wealthy, educated Virginian. Smith “oozed charm and confidence,” according to a historical account in the Fredericksburg Standard-Radio Post. “His optimism could lift the spirits of an entire town.”

Smith had previously moved to the North Texas town of Anson to help his brother Frank, who had a dry goods store. The brothers started the first bank in Jones County. When a tornado leveled their building, they cleared off the remaining wood floor and gave a dance that lasted till dawn. Temple Smith was in San Antonio on business when he heard about Fredericksburg, a thriving German community that needed a bank.

Smith was an outsider, a man of the world, who quickly demonstrated he could get things done. He founded the Bank of Fredericksburg in 1887 and hired Alfred Giles to design it. An architect who moved to San Antonio from England when he was 20 years old, Giles designed multiple county courthouses in Texas and established a 13,000-acre ranch near Comfort, naming it Hillingdon after his family estate in England. The bank he designed still stands on Main Street—now the home of Headquarters Hats—as does the old county courthouse, now the Pioneer Memorial Library.

Smith’s arrival in Fredericksburg coincided with civic leaders’ desperation for a rail connection. He organized the Gillespie County Railroad Committee, which raised money and came up with numerous plans. Finally, more than 20 years later, in 1910, the committee hired Foster Crane, the engineer who built the Medina Dam 40 miles northwest of San Antonio, to begin work on a railroad linking Fredericksburg to San Antonio via a connection near Comfort.

As the track builders worked northward, their progress slowed at the Big Hill. A crew of 250 men, along with hundreds of oxen, mules, and horses, worked 12 hours a day, six days a week for six months to complete the 300-yard tunnel. The men earned 50 cents a day, or $2 if they had a horse or mule, which meant the animal earned three times more than the man. Using blasting powder to break up the limestone, the crews removed 14,222 cubic yards of rubble from the site, Hemphill recounts.

On Aug. 26, 1913, the first train passed through the tunnel loaded with rails and ties to build tracks to Fredericksburg, and by the end of that October, Fredericksburg had a railroad. The town planned a huge celebration with a parade and speeches. Smith had the honor of driving the last spike. But the celebration was short-lived. The cost of tunnelling through the Big Hill had pushed the project over budget, driving the new railroad into receivership until it was reorganized in 1917 as the Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad, Hemphill says.

The train made slim margins carrying passengers, the mail, agricultural products, and industrial supplies, such as pipelines for oil fields. “If you see a brick building in Fredericksburg, you know it was constructed after 1913,” says Glen Treibs, a Fredericksburg historian. “Bricks, like tractors, were too heavy to be brought in on wagons.”

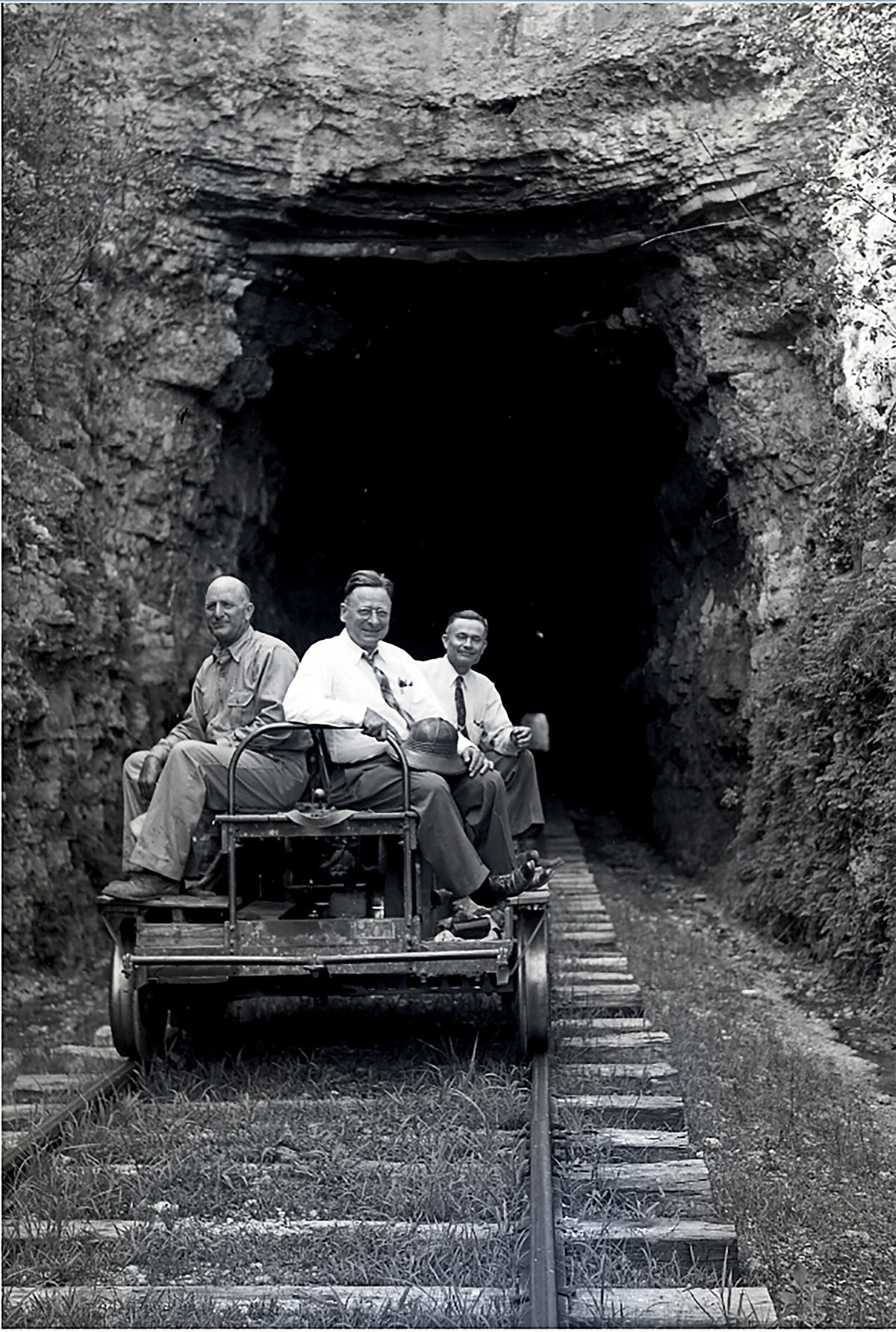

While the railroad was an improvement over using mules to pull loads from the Comfort depot to Fredericksburg, practical problems plagued the line from the start. The train derailed frequently and rarely ran on time. San Antonio-bound passengers had to change trains in Comfort, which meant a four-hour wait at a depot there. The train had to stop each time it entered the tunnel so the flagman and brakeman could walk the tracks, carrying lanterns to check for stones that had fallen from above.

Old Tunnel State Park

The builders of the Fredericksburg and Northern Railroad couldn’t have foreseen the 920-foot tunnel they blasted through a limestone hill would someday be home to millions of bats. Mexican free-tailed bats inhabit the tunnel annually during the summer months after wintering in Mexico. The size of the bat population fluctuates during the months of May through October, according to the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, because the tunnel houses a “pseudo-maternity” colony. Pregnant females use the tunnel, but pups are born elsewhere before returning as juveniles. The tunnel’s bat population is largest in August and September.

Texas Parks & Wildlife acquired Old Tunnel State Park in 1991 to protect the bats. The park opens daily with free admission, but tickets are required to stay after 5 p.m. and see the bats emerge at dusk. The lower viewing area, which provides a close-up view, costs $5 per person. The upper viewing area is further away and costs $2 per person. Both tickets include an educational program. Tickets must be purchased in advance.

tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/old-tunnel

Smith died in 1926 at the age of 80, six years before his bank failed during the Great Depression. The railroad named a depot in his honor. Now a ghost town, Bankersmith is home to a dance hall and wedding venue near Grapetown. The railroad stumbled along for 29 years in total. Plans for a health resort named Mount Alamo with a hotel and golf course on top of the Big Hill—not far from where the state park is today—never got off the ground. Toward the end, discipline was so lax that crews would stop the train to shoot game or to fish in the creeks. The last train left Fredericksburg on July 29, 1942, and a week later, the tracks were pulled up, the steel and wood repurposed for the World War II effort.

The Germans in Fredericksburg were famously frugal and suspicious of outsiders. One has to wonder how they could have mismanaged such an important project. The Big Hill and the tunnel usually get the blame, but perhaps Smith and his contemporaries fell victim to tunnel vision. For decades they had been focused on getting a rail connection. Enthusiasm won out over logic, Hemphill reasons. “It was an unfeasible project, extraordinarily expensive, but they built it anyway,” he says.

In retrospect, Fredericksburg may have been OK with no railroad. The year the train finally came to town, Henry Ford started building cars on an assembly line in Michigan. As governments got more involved in building roads, and automobiles improved by the year, the future of transportation was about to shift from railways to highways.