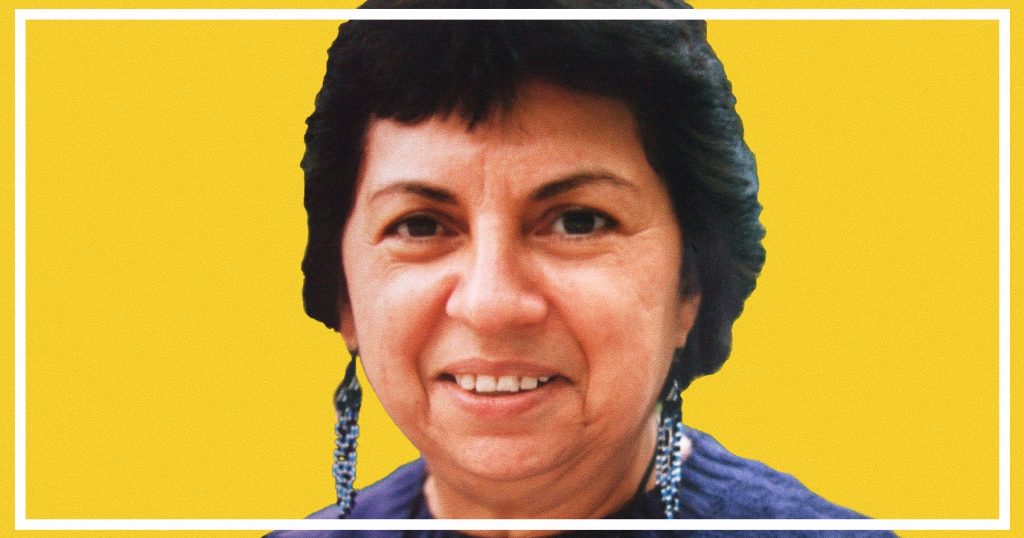

Chicana author Gloria Anzaldúa. Photo courtesy K. Kendall via Flickr, CC BY 2.0/photo illustration by Danielle Lopez

Were we going the right way? My little brother and I had never been to Hargill, a small town northeast of Edinburg, but we pressed on through the South Texas heat and the desolate backroads that cut through endless farmland that rolled into oblivion. Diesel ranch trucks roared past as we kept our faith in Google Maps.

We found the local cemetery El Valle de la Paz and soon located the grave of the queer Tejana poet, Chicana scholar, and author of Borderlands / La Frontera, Gloria E. Anzaldúa. It read: Sept 26. 1942-May 15, 2004. Hieroglyphs of snakes and lizards were etched into the headstone, and skull necklaces and rosaries left by pilgrims who came before us hung from the Lady of Sorrows statuette at the top.

It was the summer of 2022 and my brother and I had come out here without having told our mom. Sure, we were grown-ass men raised in this region of the Rio Grande Valley on the U.S.-Mexico border. But our mom, now in her mid 70s, had always been a worrier. And while she was the one who spent her days bringing flowers to family members interred at Valley Memorial Gardens in nearby McAllen, sometimes taking me to see our dearly departed straight from the airport when I came home, she wouldn’t have understood this pilgrimage. And she definitely wouldn’t have been happy with how much I spent on the fresh-cut sunflowers I’d bought at H.E.B. Not when the flowers at the Dollar Store were better because they were cheaper and lasted longer in the heat.

When I placed the sunflowers I’d brought into an empty vase, among the other flowers and a small rainbow flag that had been left there, I said hello. And as if time had collapsed, I saw Anzaldúa’s smiling face again. A queer working-class face—plain and unadorned and yet beautiful with unapologetic lived experience and a generosity of spirit. A face, I wanted to believe, like mine.

The author leaving flowers at the grave of Anzaldúa in Hargill. Photo courtesy of Erasmo Guerra

This was how I remembered her when I first introduced myself in the early 1990s at a book fair at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio. She looked like family. She was “family,” a code word I learned to use when asking other folk in unsafe spaces. I’d ask, “Are you family?,” to figure out if they were gay like me.

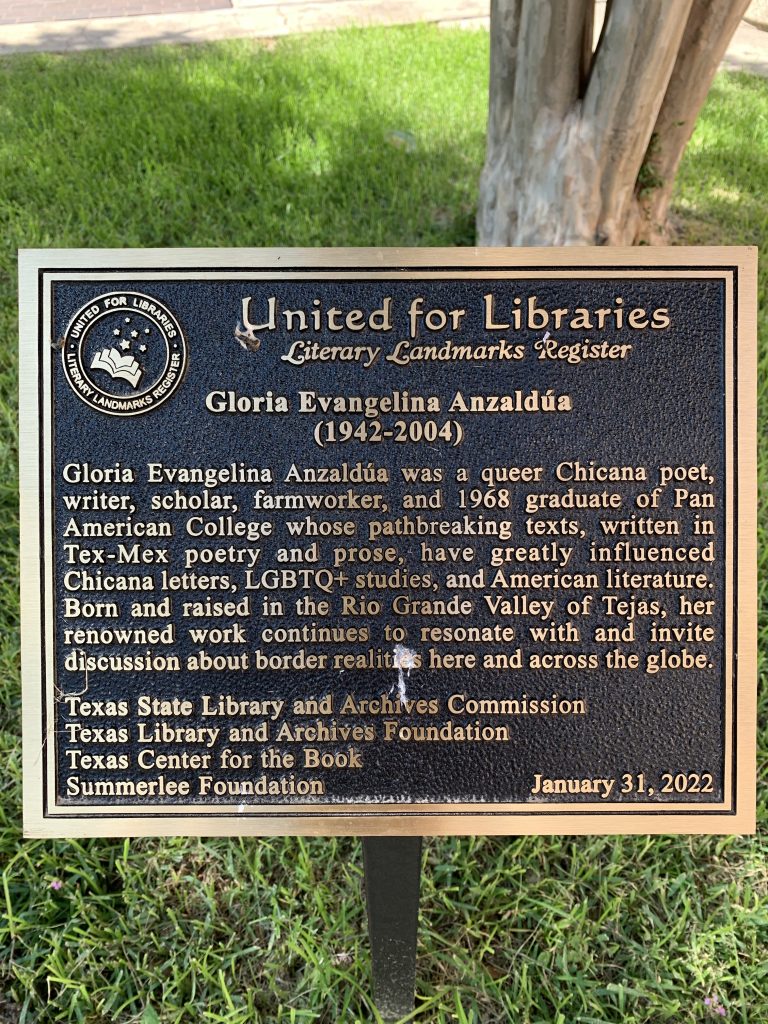

Born in Raymondville, Anzaldúa was a native of the RGV. In her works, she was known to code switch, mixing Spanish and English and Spanglish as it is spoken in the region. Through her mixing of genres—poetry, mythology, autobiography, and academic theory—she represented a kaleidoscope of personal identities. Her theory of nepantla, a Nahuatl word that describes a life between cultures and identities, or as she described it “a space where you are not this or that but where you are changing,” has been studied at college programs devoted to the study of Mexican, Chicano, queer, and feminist histories and futures. Her most notable book, Borderlands / La Frontera, explores those themes and her experiences on the South Texas border. Since her death, conferences, scholarly groups, and historical markers have sprung up focused on Anzaldúa and her legacy.

Though at the time of our meeting I knew very little about Anzaldúa, completely ignorant of the idea that writers could be from the RGV. The headliners at the book fair were members of that year’s Nuyorican Poets Café Slam team, which is why I’d wanted to attend. I was a 23-year-old college dropout in need of direction. And while I wasn’t a poet, I had been a speech and drama kid in high school. I’d won the Texas State Championship for Mission High School my senior year and had thought I’d continue down that path, making a career of storytelling.

After I heard Anzaldúa speak on stage, I forgot all about the slam poets and introduced myself to her. I told her I was from the Rio Grande Valley, just like her, and that I was thinking about moving to New York to become a writer.

“Go for it, mijo,” she said with cariño.

For the first time I felt encouraged, seen.

When I had won the state championship in speech, I told my parents the news. My late dad, a first-generation Mexican-American telephone repairman and Army vet, who’d been a migrant farmworker at my age and considered academics for sissies, shrugged at the kitchen table and offered a dismissive, “So what?”

Years later I learned my dad’s story. His father, my grandfather, wrote poetry and helped organize readings in Madero, the immigrant community on the south side of Mission where they lived. But as a kid, my dad wanted a father who loved to fight, a fearsome figure good at throwing punches, not poetry. And my dad never participated in the neighborhood floricantos because, as he lamented one day long after he’d mellowed out and we’d spend my visits home driving around in his F-150 sharing stories, “I was just a little nobody who was never good at anything.” It broke my heart to think of the generations of isolation the men in my family endured due to dumb macho insecurity.

Anzaldúa’s words of encouragement that I heard at 23 was all the permission and fire I needed. I rode a bus to New York in December of ’93, arriving during one of the coldest winters on record. I took my first creative writing class. I finished a novel that received a literary award. And then I enrolled—and finally earned—a degree at a downtown liberal arts college.

Anzaldúa had been a ’68 graduate of Pan American College in Edinburg. I wish I’d known about that back when I’d been a student there, a closeted 19-year-old, trying to find my place in the world.

My little brother had earned his master’s at the University of Texas-Pan American—renamed the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley—and he is a full professor now in the music department.

In 2022, UTRGV installed a literary landmark in Anzaldúa’s honor. Photo courtesy of Erasmo Guerra

He’s the one who alerted me that a new plaque commemorating Anzaldúa had been installed on campus when I visited in 2022.

Now, standing at Anzaldúa’s grave, I whispered, “Thank you.”

And I heard, carried on the wind, the memory of her voice, urging: “Keep going, mijo. Just keep doing what you’re doing.”

The rainbow flag at her grave fluttered. Butterflies danced over the wild daisies on the cemetery grounds and the overgrown grass swayed. The cemetery was fenced by barbwire strung on mesquite posts, to keep back the untamed monte of huizache and mesquite. The chicharras rattled loudly in the lonesome heat.

Back on the road, my brother and I drove toward the brutal shimmer that glared on the road home.

“Mijo—my son,” Anzaldúa had called me, a term of affection that got tossed around a lot around these parts, but that in this instance convinced me I belonged somewhere and to something larger in the world.