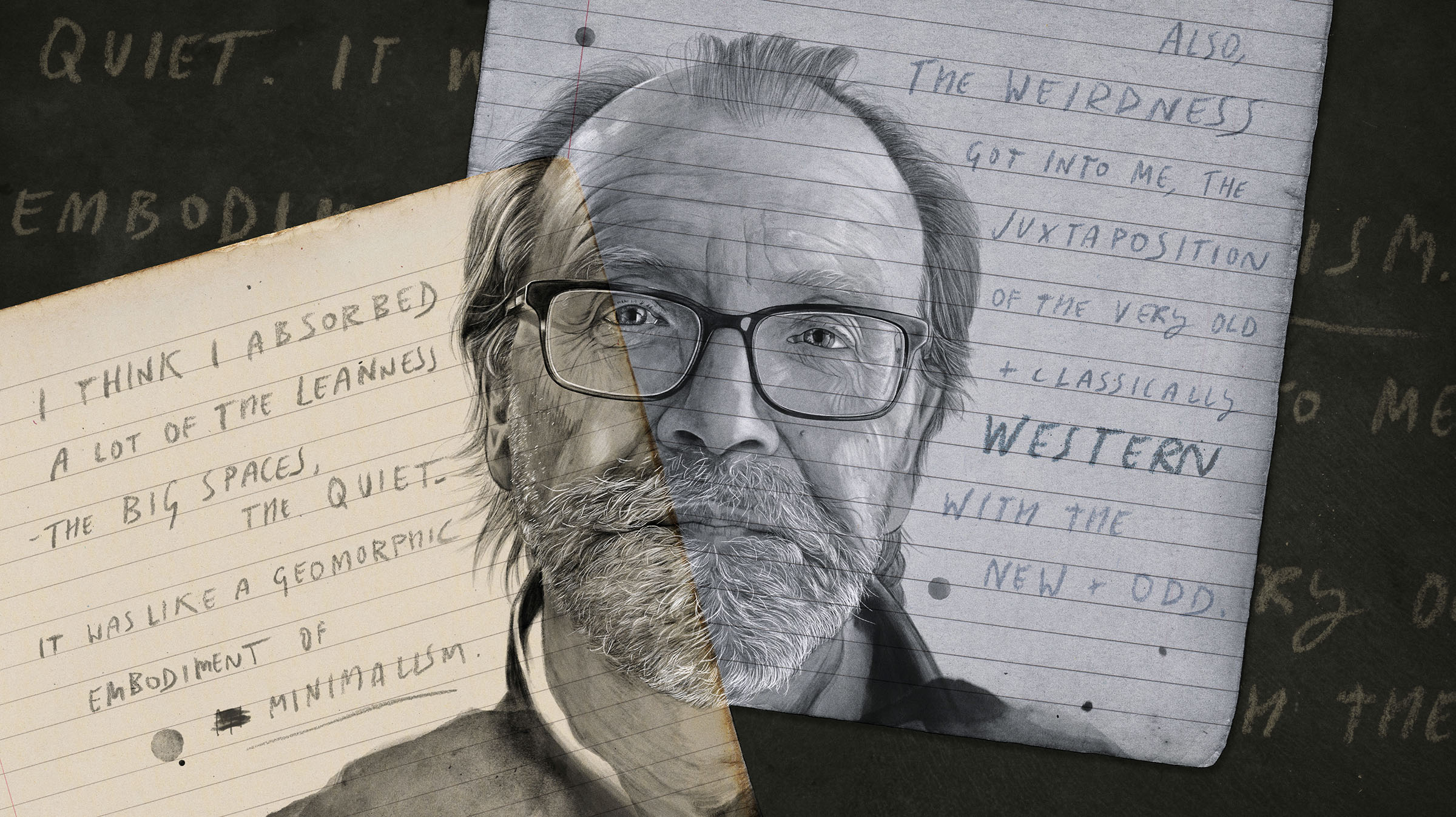

Illustration by Peter Strain

In the contemporary world of literature, George Saunders is known for many things. There are his five books of wildly inventive short fiction, including the new Liberation Day, which features nine stories echoing current society’s existential despair and political dystopia. He illuminates his love for Russian literature in his brilliant 2022 collection of essays, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. His lone novel, a haunting meditation on death and life titled Lincoln in the Bardo, was awarded the Man Booker Prize in 2017. And, perhaps most importantly, there’s his mentorship of talented writers, from Cheryl Strayed to Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, in the MFA program at Syracuse University. As a practicing Buddhist, Saunders radiates rarified humility, equanimity, and deference.

What is likely less known about Saunders: He was born in Northwest Texas hospital in Amarillo, in 1958. His father was in the Air Force and met his mother at a USO dance on the air base in town. Though the family moved to Chicago when Saunders was 1, and later nearby Oak Forest, he and his two younger sisters and parents visited his mother’s family in Amarillo every summer. Saunders remembers his Midwestern friends’ fascination with his mother’s drawl. “I always considered myself a Texan—and was proud of it and played it up,” he says. “I would say to my school friends, ‘Yeah, we went down to Texas for vacation.’”

As a young adult, in between studies and travel, Saunders lived in Amarillo for a few years, working in a slaughterhouse and then in the oil fields. Eventually, he returned to the East Coast with a pair of Wrangler jeans, a 1966 Ford pickup, and cowboy boots. “I had the whole Texas thing going on,” he says. As it turns out, there are many other aspects of Texas that have stayed with Saunders and permeated his fiction.

TH: What are some of your most vivid childhood memories of the Panhandle?

GS: We would spend two weeks every summer there with my grandparents on Alice Street in Amarillo—weeks that bordered on the mythical to me, and still do. I loved them so much and felt so loved in return. We’d drive down—straight through, 24 hours or so—as soon as my dad got off work, and then drive home the same way, all of us weeping until about St. Louis.

TH: How do you remember Amarillo?

GS: Like something out of a Steinbeck novel. A general distrust for rich people and anyone from too far away. A kind of working-class camaraderie and an aversion to being told what do, but also an egalitarian feeling and an ethos that saw courtesy as a powerful thing—courtesy to everyone, even someone with whom you disagreed, or with whose lifestyle you might not agree. A feeling of minding one’s own business, a feeling that one would rather stay quiet than offend—that this was the correct thing to do.

TH: How did you spend time with your grandfather during your summer breaks?

GS: He was a traveling salesman and sold beauty products and then, later, Sonotone hearing aids. He drove around all of the small towns up there—Pampa, Dumas, Dalhart, Shamrock, and so on. I can remember the older women we stopped to visit, in those beautiful Panhandle accents, intoning, “Oh, Mr. Clarke, I am so happy to see you.” I have a formative memory of stopping for cheeseburgers and Cokes at a pool hall in one of those small towns—the old-school formality that was so full of warmth, the feeling of being proudly introduced around by my grandfather. One of my prized possessions is a little Texas-shaped paperweight he gave me at the end of one of those summers.

TH: What sets the Panhandle apart from the rest of Texas?

GS: All that space, for one thing, and the nice things it does to your soul—that feeling of getting to a slightly higher elevation and looking out and realizing you might be the only person for 10 or 20 miles. I also found the people to have a special quality—maybe related to the landscape and history—that involved love and a dry sense of humor and a sense that everybody was in it together.

TH: Was your fiction influenced by your time working in an Amarillo slaughterhouse?

GS: I think all of my future work was informed by it. The British literary scholar Terry Eagleton said something to the effect that “Capitalism plunders the sensuality of the body”—and that was my experience of the slaughterhouse. I was a young, healthy person but had nothing left at the end of the day: no energy, no desire to celebrate anything. At times I could barely pry my hands open. After work I’d just eat and go to bed so the next day wouldn’t be terrible. So, that’s a valuable thing for a young circa-1980, person to learn—to get a sense of the wolf there inside the affable Reaganesque teddy bear.

Likewise, when I worked on an exploration geophysics crew in the summer of 1977 or 1978—one of the hottest summers on record—we’d work 10 to 12 hours a day, me and an ex-con and a few other rough customers. I’d come home from that and read The Grapes of Wrath and a light went on that said, “You can’t really write about America without writing about work.”

TH: How else do you think the Panhandle has informed the way you tell stories?

GS: I think I absorbed a lot of the leanness—the big spaces, the quiet. It was like a geomorphic embodiment of minimalism. Also, the weirdness got into me, the juxtaposition of the very old and classically Western with the new and the odd. I remember coming out of a funeral and, across the street, was one of those Chuck E. Cheese places, and the guy in the rat suit was taking a smoke break under one of those crazy orange Panhandle sunsets.

TH: Is there a particular collection of yours that you feel is most in conversation with Texas?

GS: CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, just because this feeling of new, corporate America slapped down across old America is very alive in that book. There’s a story in there called “The Wavemaker Falters” that ends in what I consider some very West Texas imagery—a guy in a desert alone at night.

I used to play in a country-western band out on old Amarillo Boulevard, and I found that to be a very deep experience—talking to people on breaks between sets, mapping out the complicated and funny and sometimes difficult stories of their lives there in Amarillo. That quality has, I hope, made it into my work; that feeling of people working hard, sometimes failing, but still loving life enough to come out to have a good time.

TH: Do you have a favorite Texas writer?

GS: I didn’t know until I just now Googled it that Elizabeth McCracken is a Texan. I love her work. Cormac McCarthy, of course, and Larry McMurtry, and the great one, Katherine Anne Porter.

George Saunders’ newest book is Liberation Day: Stories. For more information about his work, visit georgesaundersbooks.com.