I’ll Give You My Last

A Houston native returns home from Harlem to heal alongside his family

An earlier-than-anticipated death is not ideal, especially to go out in such an unfortunate way.

It’s partially my fault for even needing directions from the airport in the city I grew up in, but in my defense, I had a right to be slightly confused. So much of Houston remains the same, but my eyes can’t help but notice all of the changes. Like how the Airbnb I was staying at was listed as located in the “EaDo” area. I had no idea what it meant, but apparently thanks to realtors and new arrivals to Texas, it’s a cute nickname for East Downtown.

On arrival at my Airbnb, I realized I was basically in Third Ward, given Emancipation Avenue was right behind me. Some might be more specific and say I was staying in Old Chinatown. I did recognize the Kim Son restaurant my mom used to order General Tso’s chicken from and that my best friend still swears by. Still, there was a lot of construction going on, and I couldn’t keep up.

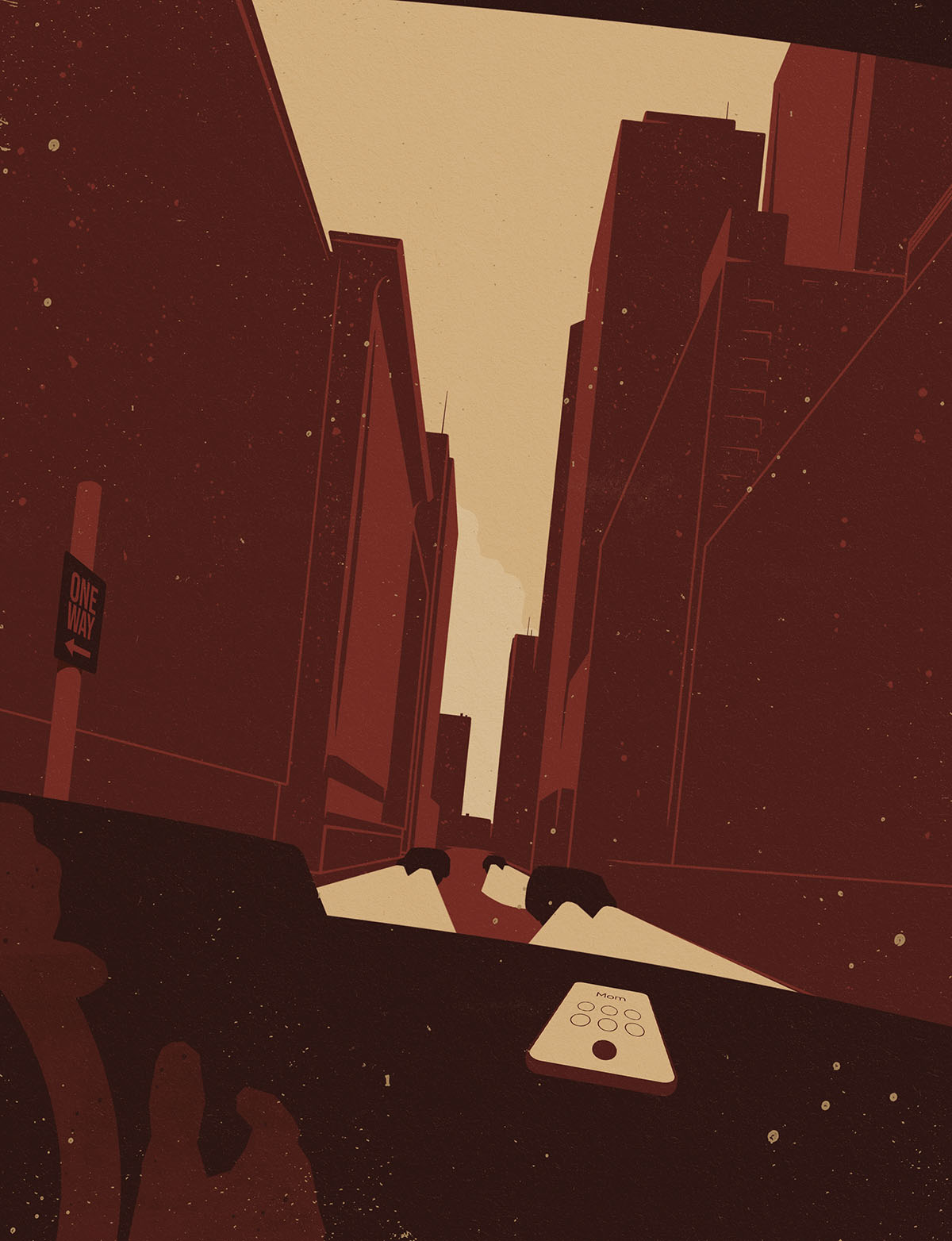

Evidently, neither could the I app I was using to help find my way. That right turn I was directed to make sent me down the wrong way on a one-way street just seconds before the lights on the other side turned green. The app in question shall remain nameless, but I will never shut up about the brief terror it put me through.

The cars were going so fast, I had no time to be startled. Lots of honking horns from drivers, and I’m fairly certain several people wearing face masks were cussing me smooth out. I suppose I can see their point of view from their side of the street, but I swear on my love of Megan Thee Stallion that it was the app—not me! I admit, I have struggled with parallel parking, but I know how one-way streets generally work.

At this point, I was already in Houston for a lot longer than I had anticipated.

Back before the pandemic began and my eventual retreat to Houston, my 2020 plan was as follows: finish the book tour for my second essay collection, I Don’t Want to Die Poor, and leave New York City forever. I had been living in Harlem for seven years. The first years were good, but the rest were a mixed bag. As time wore on, I felt more distant from most members of my family back in Houston. The problem was magnified when I started coming home far less often because I just didn’t have the money and was too proud to ask for it.

Freelance writing can be difficult to juggle on its own, but when you couple it with sizable student loan debt, every check matters. When I finally got in a better financial position, I wanted to reclaim missed time with my family by spending a couple of months in Houston before making my way to Los Angeles to forge a career writing for TV.

Simply leaving Houston never made my life any better either. It’s why I liked D.C. until I didn’t. The same for LA. And then New York. The only thing that stuck was my accent, which followed me everywhere. I have only ever identified as a Houstonian and Texan—like Beyoncé.

But then life as we know it came to a stop. I adjusted like everyone else and did my book tour and everything else from my tiny New York apartment, a place I had long ago grown to hate. I will always appreciate the exposed brick, but hearing all of those sirens signaling death did a number on me. I love Harlem, even though it was generally too loud of a neighborhood even before the plague. By mid-fall, when I knew it would only get darker, colder, and lonelier there, I decided I couldn’t take it anymore.

Initially, it felt good to be home. But as much as I love Houston, I can easily be thrown off course to disastrous results. After successfully swerving away from several potential car crashes—avoiding death by wrong turn at the age of 36—I managed to get to US 59/Southwest Freeway without a scratch. This trip back to Houston was supposed to be relaxing, but it would be one drama after another.

I was in a rental car heading to my real home on the southside of Houston, in an area known as Hiram Clarke. I recall hearing it referred to as an “inner-city neighborhood” during an assembly at James Madison High School, or “Hiram Clarke High.” I would describe it as a collection of neighborhoods joined by Hiram Clarke Road. No matter which specific subdivision you’re in, you’re likely to see an old sedan converted into a “slab.” Also, Screwed Up Records & Tapes, a record store selling music by Houston hip-hop icon DJ Screw, is in Hiram Clarke—not far from a Jack in the Box that will outlive us all. I ate so many Extreme Sausage Sandwiches during my senior year of high school that I can never eat them again, but thankfully, a Breakfast Jack still hits and doesn’t expand my belly as much.

I’ve always been tickled by the way Hiram Clarke is pronounced on local news (Hi-rahm Clarke) as opposed to how those who live there say it (Harm/Herm Clarke, depending on your twang). I was heading there for my mama’s comfort and a side of brisket. But I was met with another needless reminder of how fragile life is in the process.

While at a stoplight, I gave her a call.

Hey, Mama. I just got sent down the wrong way on a one-way street. I’m OK. But I would have been so mad at myself for dying because I know that would be such an inconvenience to you given the week you’ve had.

Her voice, in its Louisiana-shaped glory, always calms me. She laughed a little bit for my sake, but she told me she detected anxiety in my voice. I took her advice to get off the phone, watch the road, and remember to breathe.

I worry my mom enough as it is. I have not used that app since.

Less than a week before, my dad suffered an injury at work that likely would have proven fatal if not for a caring coworker who knew to take him to a clinic, and subsequently, have him rushed to the emergency room. The worst was avoided, but I hated that we all had to endure such a scare in an already dark year. One where individually and collectively, we had already suffered so many losses.

It made my recent choice to finally flee New York and spend time at home, around my family, feel like the right one. The irony is not lost on me that as much as I love my dad, he’s also the reason why I hadn’t been home as often as many would have liked over the previous decade. It would have really sucked for either of us to go out right as I was trying to right the wrong of such long-standing absence.

It’s hard enough for anyone to have a successful career as a writer, much less someone like me—Black, working-class, from the South, who knows none of the kinds of people doing any of the things I have imagined doing.

I love and appreciate my parents, but it was a difficult home to be raised in. And one parent was more responsible for that than the other. My dad’s angry outbursts, often enhanced by drinking, were typically directed at my mother, but he tormented all of us with his tirades. Human beings are complicated, and in the case of my dad, I have a deep understanding of the phrase “hurt people hurt people.” Still, the darker parts of my past and his anger that fueled them have overshadowed my childhood and followed me into my adulthood.

I have worked to understand why, but where I have failed is in learning to forgive and forget. I have been carrying the baggage of my childhood with me throughout my entire life, which prevented me from enjoying adulthood fully. I have long said that if I don’t learn to let it all go, it’s going to continue to haunt me. Yet I really never did much to correct the issue. Distance was just a way to provide relief. Some periods have lasted longer than others, but ultimately it all ends the same: I sort of lose it, break down, and find myself with many of the feelings I had as an 18-year-old seeking both a professional dream and to end some internal nightmares.

Since college, I have lived in Washington, D.C., LA, and New York. There were some brief stops back in Houston along the way, but each stint made me recall why I left in the first place, especially the night I had to be physically separated from my dad. It’s hard enough for anyone to have a successful career as a writer, much less someone like me—Black, working-class, from the South, who knows none of the kinds of people doing any of the things I have imagined doing. I needed focus, and it had become abundantly evident that being too close to the root of my traumas prevented me from reaching my full potential. I love Houston so much, but it’s often been hard for me to stay there longer than a couple of days as an adult.

At the same time, simply leaving never made my life any better either. It’s why I liked D.C. until I didn’t. The same for LA. And then New York. The only thing that stuck was my accent, which followed me everywhere. I have only ever identified as a Houstonian and Texan—like Beyoncé.

In New York, the struggles were mostly related to real estate. Someone once said Texans make the best New Yorkers, but that person must have been rich. I hadn’t vacated my dungeon in Harlem because I simply couldn’t afford to. Then a pandemic happened.

For the greater good, I felt like it was my responsibility to buckle down and stay put. New York is a great place for people who enjoy what it provides, but without access to the stuff that makes paying such high rent feel worth it (museums, proper restaurant dining, the theater, clubs and bars, comedy clubs, concert halls), all you have is your lonely self on an island.

I was left with my own thoughts, which weighed me down more the longer I lingered with them. I was fortunate to be working throughout the pandemic, but work can only distract you from yourself for so long. That, more than anything, is why I ended up leaving under a wave of sadness, anger, and loneliness to another place where the cycle is bound to repeat itself.

Near the end of last summer, my mom said something that caught me off guard: “I know it’s hard for you to come home because as much as you love us, you dealt with a lot of pain here.”

In the first few weeks back, I felt generally more at ease. Some of that was because of the “easier” aspects of life in Houston versus New York, like more space, more sun, more fried alligator.

It broke my heart to hear her say it. I started to cry on the phone. It’s not like I hadn’t written or told friends as much, but I never wanted to admit that to my mom. I never wanted to hurt her feelings because I love her so much. Many of us can have complicated relationships with our folks, but most of us dare not ever say anything that feels like a slight, especially when we know how much they have sacrificed for us.

Although she said it for the both of us, she argued that even if it didn’t feel like it, it was in my best interest to come back to Houston. This time, I didn’t immediately disagree. She was right to say I needed to be closer. We both knew it was time I stopped running away from the problems that were going to keep following me no matter where I laid my head. LA could wait.

In the first few weeks back, I felt generally more at ease. Some of that was because of the “easier” aspects of life in Houston versus New York, like more space, more sun, more fried alligator. I no longer have to go to a laundromat because my Airbnb has a washer and dryer. Also, it’s better to drive to Shipley Do-Nuts than to walk to Dunkin’ Donuts.

Despite the perks, I was still overly emotional. I cried in conversation with my mom when we talked about what’s kept me away, and I was angry when greeted by some of those very triggers directly. None of it was comfortable, but all of those emotional outbursts felt necessary. They were confirmation that I am not as over the past as I’ve professed.

Plagues suck, but they do provide good rationale for people to stop pretending—should they have the will.

My dad is my dad. He always says to me, “I’ll give you my last.”

That has always been true, but at this point in my life, that’s not what I want from him. I want to have a conversation in which I express what I feel were his mistakes and he says, “Son, you’re right, and I apologize.” But that’s not going to happen. His brisket—the one I was driving home to get, along with a hug from my mom—is more tender than his conversation.

In my adult years, though, we’ve at least been able to say “I love you” to each other. Now, we even hug. I have to take what I can get, appreciate it all for what it is, love him deeply all the same, and meanwhile, look elsewhere for the resolution that will give me the total peace that’s long evaded me. I need to take charge of my own healing.

I’ve driven by it more times than I can count, but I hadn’t actually been to Hermann Park in more than a decade. It’s still hell to find parking, but the park is even prettier than I remember. At 445 acres, it’s about half the size of Central Park, but contrary to Texas standards, bigger isn’t always better. I’m just glad Houston was able to seize control of its stereotype as a concrete jungle and the smog capital of the U.S. and invest in making this plot of land a natural beauty. It sure beats the choked roadways—and the app—that nearly hastened my death.

I had arrived with my sister for a walk along the trails. As we visited, I told her my problems will only follow me wherever I go. She reminded me that she’d told me that several years ago.

My sister has a way of centering me. She helped me realize I didn’t need a serious scare about my dad or myself to remind me to value life. But if nothing else, I did get the kick in the butt I needed to understand that we are all only here for an allotted amount of time. We are not in control of how long, but we can control how we spend the time we get. I have had a lot of good in my life in spite of so much pain. I need to stop picking at the scabs already.

I was happy to be outside in the fresh air after a year pent up inside. At one point, my sister and I walked around the Japanese Garden. It wasn’t the best time of year to see it, but it was still beautiful to witness. I made a bad habit of not noticing much about the ground around me on foot in New York. But part of being back here was to be still and notice. I’m glad my sister was getting me to do that here and elsewhere.

I still want to head out to LA, but I have decided to stay in Houston until I’m ready, or vaccinated. My main concern isn’t timing, but instead making sure I don’t leave with a chip on my shoulder or an underlying sadness. I don’t want to be so easily triggered anymore by someone else’s failure to change. I am closer to 40 than 30 now, and I don’t think it’s fair to me or those who love me to still be caught up in what happened so long ago.

I want to figure it out. I want to heal. And finally, after all this time, I recognize that none of that can happen if I don’t start the process in the place where all the hurt started.

Before it became a destination in its own right, Hermann Park was mostly a no man’s land—a cut-through to other destinations. I didn’t want this trip to Houston to be the same. It’s exactly the place where I need to be, and I didn’t need an app to get here. Some places you just know by heart.