Sixteen years after his death in October 2006, Freddy Fender still isn’t in “hillbilly heaven.” That would probably irk him.

“Hillbilly heaven” is how the legendary singer from the Rio Grande Valley referred to the Country Music Hall of Fame. Created by the State of Tennessee and the Country Music Association in the 1960s, the Nashville-based nonprofit and its museum honor the heavyweights of the genre, from Roy Acuff to Faron Young.

It was Fender’s nature to joke about it, to pretend it didn’t sting. It was also a sly reference to the old Tex Ritter hit “Hillbilly Heaven.” But Fender really did want to make history.

“Hopefully, I’ll be the first Mexican American going into hillbilly heaven,” he told The Associated Press in 2004.

The designation remains an elusive milestone in Fender’s storied legacy. Born Baldemar Huerta in San Benito on June 4, 1937, Fender was a country music pioneer who mixed the influences of Tejano, R&B, and honky-tonk into his own Tex-Mex style. He’s remembered for his smooth, heart-wrenching singing; his incorporation of Spanish lyrics and successful crossover to mainstream country; and his flashy, big-hair fashion. But it’s not clear he’ll ever make the Hall of Fame.

“He may not be a Loretta Lynn, but he’s at least a Crystal Gayle,” says Michael Morales, a San Antonio musician and record producer who made two of Fender’s albums. “His problem was he didn’t die young enough. But I think they’ll eventually do the right thing.”

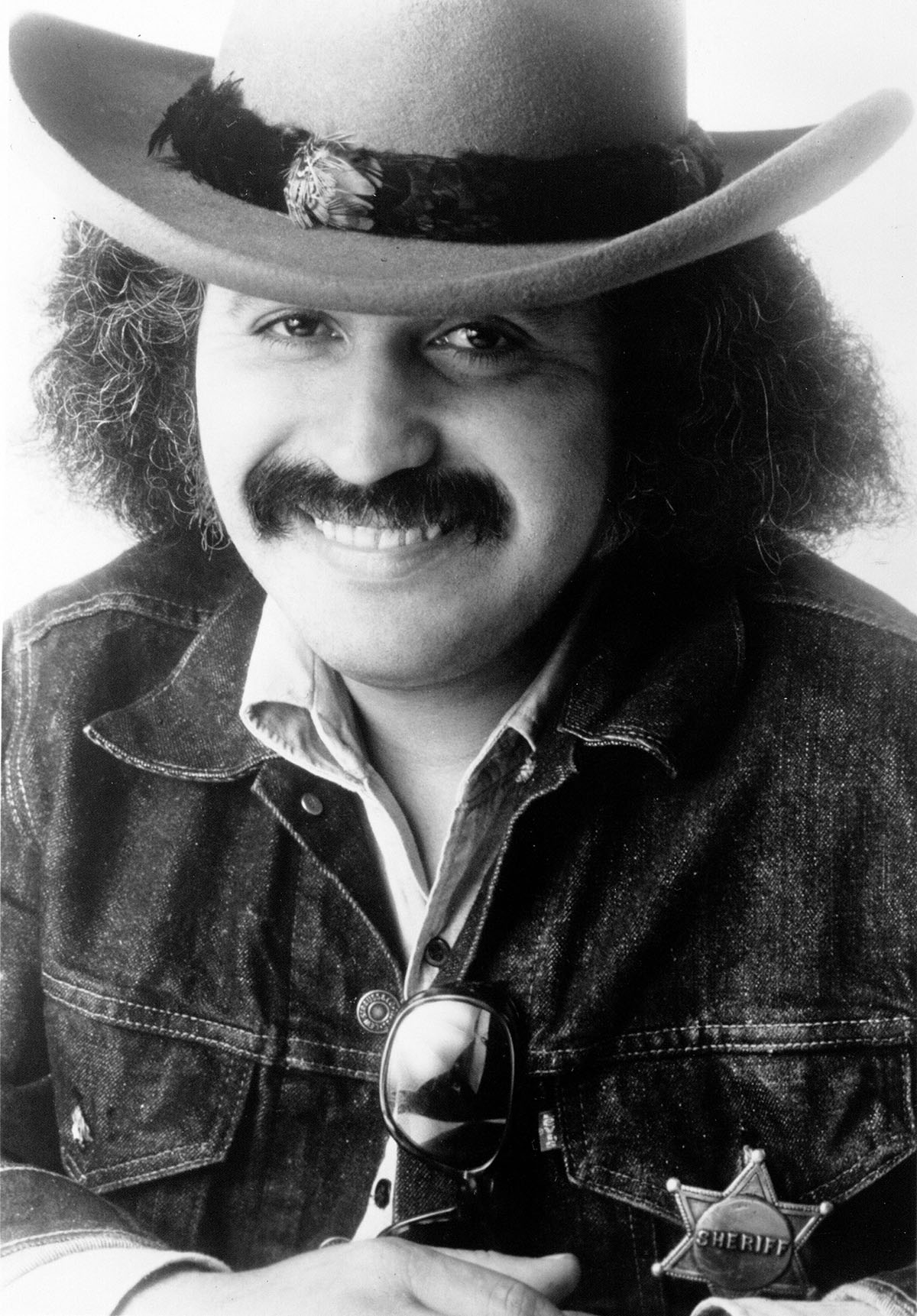

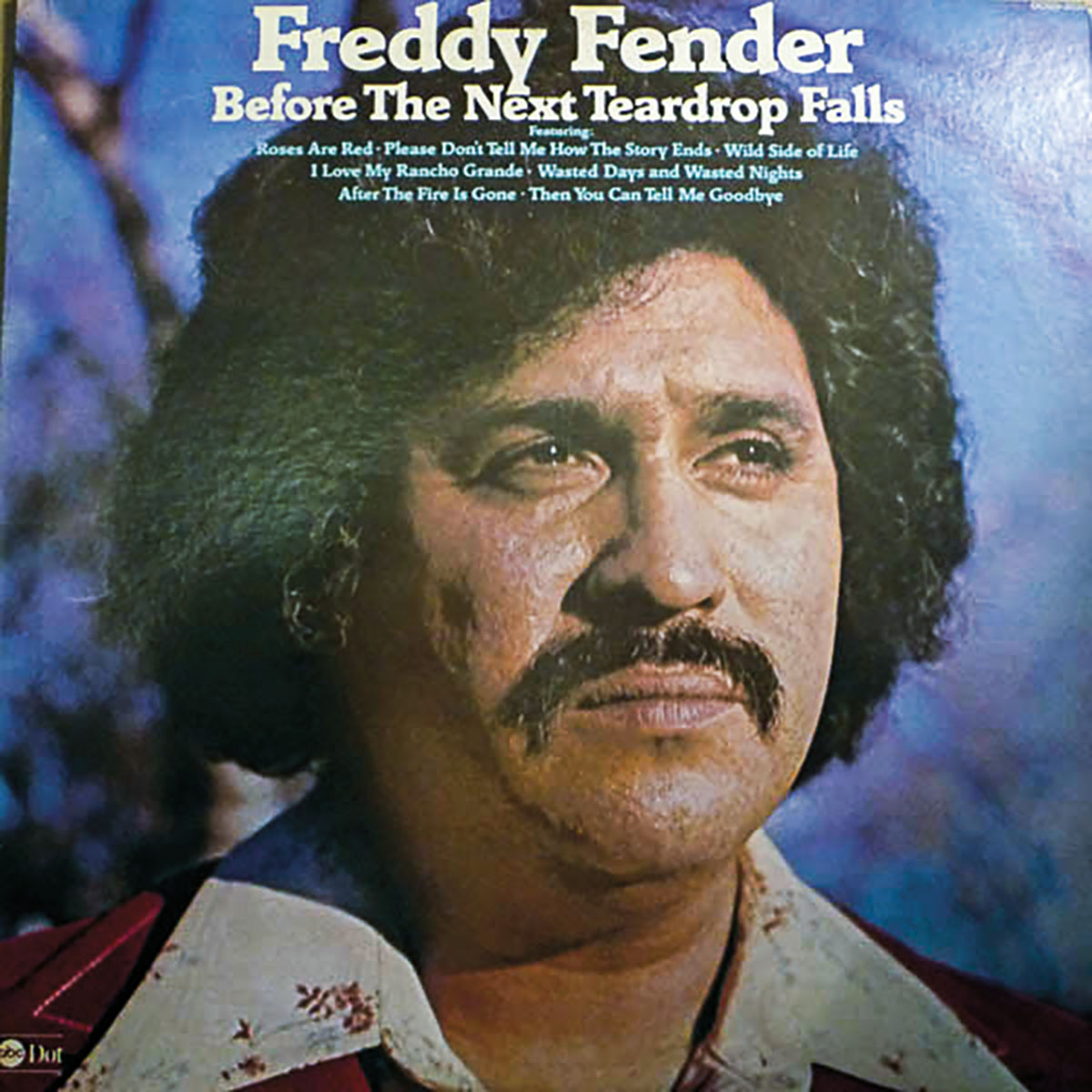

Certainly, Fender’s life story is as wild and compelling as the legends of country’s favorite icons. He’s garnered two No. 1 hits: The bilingual “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” and self-penned “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” are jukebox staples. Fender’s also got the rough-around-the-edges outlaw image. With his trademark blown-out fluff of curls, he was always instantly recognizable. Always authentic.

Not many country musicians have followed as circuitous a path as Fender, whose career is remembered for three distinct phases. As a teenager in the mid-1950s, Fender was a founding father of Chicano rock ’n’ roll and rock en español; he was known as the “Mexican Elvis” and “El Bebop Kid.” He reworked songs like Elvis Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock” (“El Rock de Carcel”) and Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” (“El Twist”). With a grittier sound than contemporaries Ritchie Valens and Mando & The Chili Peppers, he topped the charts in Mexico and South America.

In the mid-1970s, Fender made an unlikely comeback as a paunchy bilingual country music star, scoring radio hits and touring the country with a thick mustache, denim suits, and butterfly collars. In his heyday, he was hanging out with celebrities like Dean Martin, Dinah Shore, Olivia Newton-John, and Johnny Carson.

Fender reinvented himself yet again in the late 1980s and ’90s with the Texas Tornados, a Tejano supergroup also featuring Doug Sahm, Flaco Jiménez, and Augie Meyers. The band won a Grammy Award in 1990 in the category of Best Mexican-American Performance for their version of “Soy de San Luis.”

The thread woven throughout each chapter was Fender’s vocals. There was a mournful cry to his tenor voice, and the articulation in the phrasing made every word count. “He was a real emotional singer,” recalls Jiménez, the renowned accordionist and conjunto music’s greatest ambassador. “You could see his heart. What he was singing, he had lived.”

Nicknamed “Balde” as a child, Fender was born at home on Biddle Street in the San Benito barrio known as El Jardín. The family was poor. His father, Serapio Huerta, a vegetable packer, died of tuberculosis when Fender was 8. His mother, Máge, struggled to feed and clothe her five children.

Fender’s daughter, Tammy Lorraine Huerta Fender, described the sparse living conditions in her biography, Wasted Days and Wasted Nights: Freddy Fender, a Meteoric Rise to Stardom, which she self-published in 2017. The family lived in a one-room tin house with dirt floors and no indoor running water. Young Balde would scour dumpsters for produce; sometimes he would steal. To lighten their worries, Máge sang old Mexican love songs to her children at night.

“Her singing brought comfort to them when they were in doubt of tomorrow,” Tammy Fender wrote. The family traveled the country as migrant farm workers. In Michigan, they picked beets; in Indiana, cucumbers. Tomatoes and hay meant they were in Ohio. In Arkansas, they picked cotton. In New Mexico, onions.

As a kid, Balde fashioned a guitar out of a sardine can, wire, and wood scraps. His first real instrument was a $9 Stella guitar. Later, he was partial to Fender electric guitars, and in the late ’50s adopted the stage name Freddy Fender because he liked the way it sounded.

About 50 years later, in 2002, Fender revisited the songs of his childhood with the album La Música de Baldemar Huerta, mostly featuring songs in Spanish. It was Fender’s only solo album to win a Grammy Award.

Homegrown Talent

Though Freddy Fender died 16 years ago, he’s still hard to miss in San Benito. His hometown famously celebrates the singer with his image on a municipal water tower on US 83.

Nearby, Resaca de los Fresnos runs through town. When he was a boy, Fender swam across the 80-foot-wide channel to impress his friends. Freddy Fender Lane runs alongside a portion of it.

Though the shack where he was born near 550 Biddle St. is gone, the San Benito Historical Society is working with Fender’s widow, Evangelina Huerta, to install a historical marker at a nearby home on Freddy Fender Lane where the couple lived after they got married.

Fender is buried at San Benito Memorial Park Cemetery, 2060 N. Sam Houston Blvd. His massive black headstone is etched on one side with the image of the singer playing his electric guitar, basking in the spotlight. On the other side of the stone, the name Baldemar Huerta dwarfs the name Freddy Fender. “Vaya con Dios,” it reads. “From my humble beginning to a humble end.” Six pedestals at the site hold bronze plaques that tell Fender’s life story.

The Freddy Fender Museum on Heywood Street closed during the pandemic and remains closed. The City of San Benito is working to reopen the exhibit, though no date is set. The collection includes photographs, albums, a guitar, stage costume, and his beloved Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

As a teen, Fender was a street fighter. He dropped out of school and enlisted in the U.S. Marines at 16. After a tumultuous three years, he returned to San Benito, started his music career, and in 1957 married his lifelong partner, Evangelina Muñiz. Fender wrote “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” in 1959, but his career was upended within months when he was convicted for marijuana possession in Louisiana and spent nearly three years in jail starting in 1960. Fender and Muñiz eventually moved back to Texas, residing in Corpus Christi. But his music didn’t regain traction until “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” in early 1975.

That same year, at the height of his fame, Fender described to Newsweek how he came up with songs. “I write born loser songs,” he said. “I absorb punishment, and it makes me very sad. … I get really sad and put it into my songs.”

Nashville country music journalist and artist development consultant Holly Gleason says Fender should be in the Country Music Hall of Fame. There are few like him, she says, who reflect “a cultural reality” and “country’s future.”

“His voice conveyed emotion like razor wire, which is very much a hallmark of country music,” Gleason says.

There are 149 members of the Country Music Hall of Fame. An anonymous panel of voters chosen by the Country Music Association elects three inductees each year—a modern era artist, a veteran artist, and a third rotating category that includes nonperformers, recording, touring, and songwriting.

Veronique Medrano, a Brownsville-based Tex-Mex country musician and archivist, has made Fender’s Hall of Fame inclusion her cause. It’s part of her larger effort to draw attention to the contributions of Latino artists in country music. This past June, on the 85th anniversary of Fender’s birth, Medrano started a petition on change.org to get Fender into the hall. The petition has about 3,500 signatures so far.

“There is an assumption that Freddy Fender is already in there,” Medrano says. “People are stunned to learn he’s not. He is the golden child of Mexicanos here in the Rio Grande Valley.”

Only time will tell if Fender ever finds his way into “hillbilly heaven.” Whatever the case, he’ll long be remembered for his contributions to country music and Tex-Mex culture.

“He was a pioneer in breaking down boundaries,” Gleason says. “Freddy is totally important. ‘Before the Next Teardrop Falls’ is so potent and iconic. He should be in just for that.”