The Wind Between Us

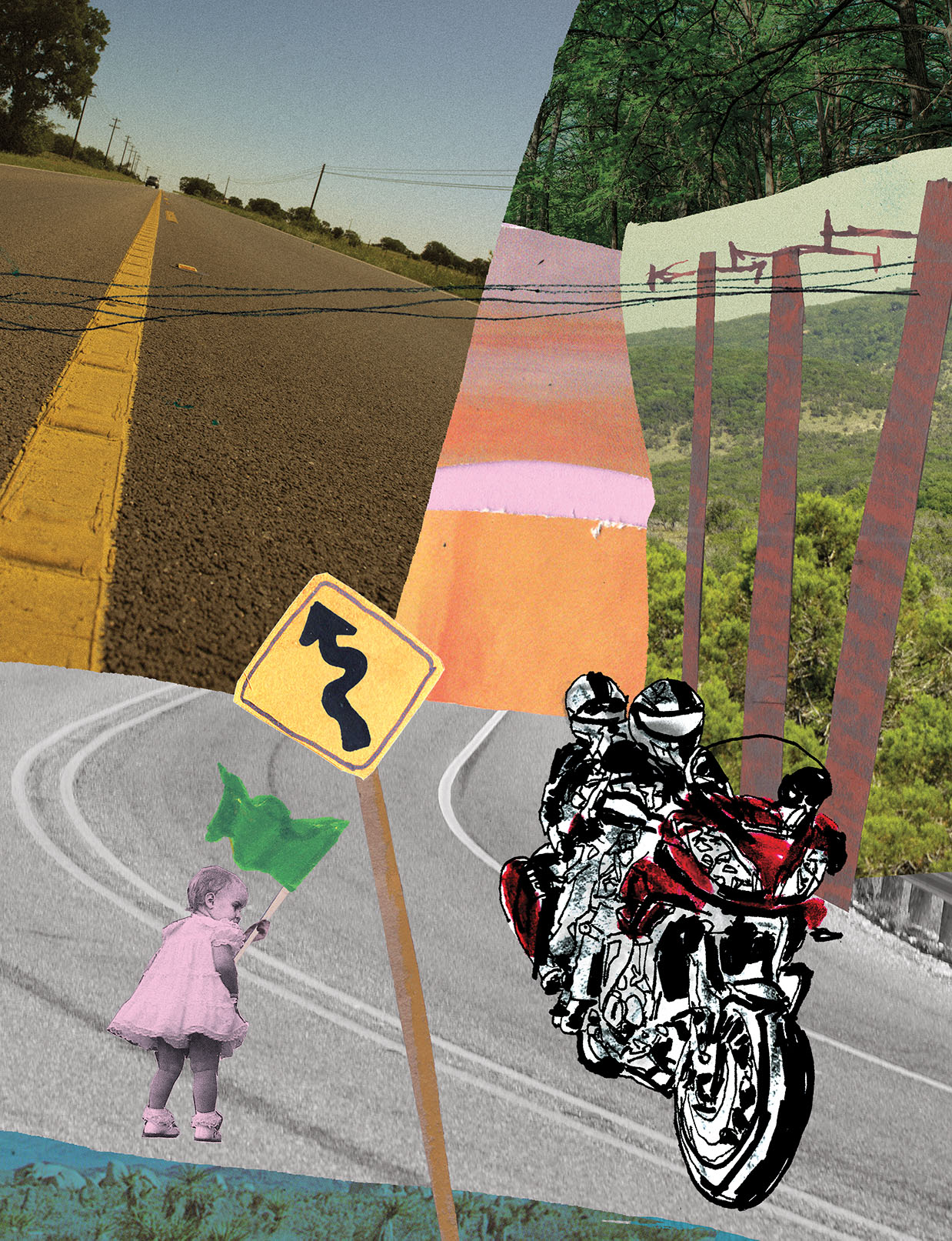

A mother reclaims her freedom on the Devil’s Backbone

By Katie Gutierrez

A pearly silver hearse pauses at the mouth of Purgatory Road. The timing is so perfect it seems almost staged. I’ve been noticing the symbolism everywhere, from the rot of furred flesh melting into pavement to the painterly flourishes of crimson foliage in the hills: harbingers of death. For the first time in three years—since becoming a mother—I’ve climbed onto the back of my husband’s motorcycle, and I can’t shake the guilt of doing some-thing selfish. Something reckless. Something that could take me away from my children, even if it brings me back to myself.

Before dating my husband, Adrian, I’d never ridden a motorcycle. I thought riding was dangerous and foolish, an inherently selfish endeavor if you had people who cared about you. But Adrian is a lifelong rider, starting with dirt bikes as a kid at his family’s 30,000-acre working sheep station in Queensland, Australia. And one day, he invited me to join him.

In the dark garage of his Sydney apartment building, he helped me fasten his extra helmet over my head. He held the handlebars and grinned as I climbed onto the bike—gingerly, as if it were an animal that might bite—and then swung his own leg over with practiced grace. I clung to his waist as the engine turned, cracking open the silence inside my helmet.

“Ready?” he asked over his shoulder.

I tightened my grip.

“Ready,” I said, though I wasn’t.

We eased onto Flood Street, then Bondi Road, past the dry cleaners and the organic bedding store and the barbecue chicken shop with fresh salads, past the wine store and the butcher shop and the grocery where avocados and blueberries cost three times what they did back home in the U.S. The salty airlifted the hair at my neck, and as we came around the corner downhill, the ocean splintered the earth, drawing an azure curve around bright sand and rocky headlands.

I realized, to my surprise, I was grinning. The world around me was suddenly so immediate. The street rushing close enough to touch, the sun warming my arms, the smells of ocean and gasoline and Italian food and cigarettes, the sunbathers and skaters and wet-suited surfers—and Adrian’s hand joining mine at his sternum. When you’re in a car, you’re an observer. On a bike, you’re a part of things. You are motion itself.

It felt like waking up. It felt like falling in love.

Adrian and I met on a plane in 2004 and kept in touch online in feverish fits and starts over the years, but it wasn’t until 2012 that we decided to try for a real relationship. Then, after two years of Skyping at odd hours and seeing each other twice a year, Adrian moved from Sydney to San Antonio to be with me. One of his first purchases—after an engagement ring—was a Triumph Tiger. Buying the Triumph (and getting his Class M license) was his way of planting a stake in the ground, an effort to make Texas home.

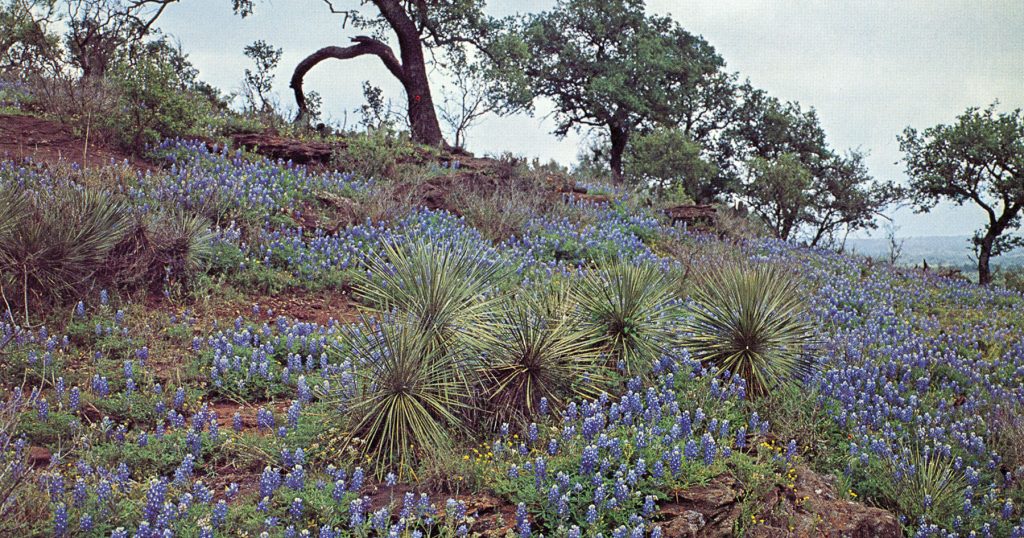

In 2014, one of our first rides here took us on an unplanned detour to Guadalupe River State Park. It was near closing hour as we wove through the tangled river-bank root systems of large bald cypresses on Park Road 31. Prickly Texas thistle grew wild, fuchsia bulbs swaying. Diffuse sunlight made the limestone outcropping on the other side of the river blush rose gold. The river swept gently around the boulders in its path like secret lovers touching in a crowd. I couldn’t believe it had taken the bike to bring me here for the first time.

As we began riding more frequently, at least every weekend, Adrian bought a Bluetooth intercom system for our helmets so we could listen to music and talk to each other on the road. He researched women’s bike gear, and one by one pieces arrived in the mail: a bike jacket, textile pants, ankle boots. Now, they all stand out like armor in a closet of bright colors and floral prints.

One of our favorite rides was out to Fredericksburg via Ranch-to-Market Road 473 and RM 1376. We stopped in Sisterdale at Sister Creek Vineyards, whose tasting room is a red barnlike building with an entry marked by bales of hay stabbed through with the U.S. and Texas flags. We stopped in Lucken-bach, always crowded with bikers, and explored the old Post Office and General Store before listening to live music from a long picnic table.

In Fredericksburg we liked to eat at the basement bistro at Vaudeville: French dip sandwich for Adrian and marinated chicken confit salad for me. We followed it up with a full-bellied stroll down Main Street and perhaps a quick ride to the unassuming Alexander Vineyards to re-up on the Champagne we saved for special occasions.

We took backroads and detours, and images from these trips rise to mind like fragments of dreams: the citrine-yellow farmhouse Adrian photographed beneath a purple starry sky, the incongruous glimpse of zebras strolling among the mesquite trees of what turned out to be an exotic wildlife ranch, the cluster of baby goats that rushed to the fence line once we turned off the bike and called to them. There is a crystal-clear waterfall somewhere that feels like a secret, known only to us.

Riding was more than just something to do on the weekends. It was our way of reconnecting, with each other and ourselves. When I was stuck on the novel I was writing, we’d hop on the bike. It was a shortcut to lucidity, where a plot thread might finally untangle or whole paragraphs might scroll across my mind. Riding brought us not only closer to each other, but closer to the parts of ourselves that sought some new understanding of the world.

It wasn’t as though I’d forgotten the danger. To ride, whether in the front or the back of a bike, is to enter into a contract with yourself: “Yes, I understand the risk, and I accept it because if the worst were to happen, I would leave this earth in the midst of experiencing the best parts of it, and isn’t that the most any of us can ask for? Isn’t it more than many of us receive?” Still, there is no one I would trust more on a bike than Adrian.

But then, in 2017, after a struggle with infertility, I got pregnant. I was probably eight weeks along when we took our last ride. Soon after that, the pregnancy became painful. More importantly, I was becoming more attuned to the life inside me, its shape transforming on sonograms into one we could recognize as a tiny reflection of ourselves. It suddenly felt wrong to ride.

The pain lessened when our daughter was born, but for months all I could focus on was keeping a baby alive. Much later, when time began to slowly open up again, my desire to ride was complicated with the knowledge that if, indeed, the worst were to happen, our daughter would be orphaned. What could possibly be worth taking that risk?

This question still looms in my mind, three years since my last ride and now that our second child is 2 months old. But I’m also aware of an expectation placed on mothers to subsume our own desires, our sense of risk and adventure, for the sake of our children. Women online talk about “mom guilt” and flagellate them-selves for the occasional “selfishness” of attending to their own wants and needs. But when I hear selfish, I think selfhood. Why should we apologize for temporarily reclaiming ourselves from the small hands that reach for us all day long?

This sense of defiance leads me back to the motorcycle. My parents, who will be babysitting our children, aren’t happy about Adrian and me riding off. My mother looks at me as if it might be for the last time, as we wave goodbye in the driveway. I think of Samanta Schweblin’s frightening, excellent novel Fever Dream, whose original Spanish title is The Rescue Distance.

The rescue distance refers to the distance at which a mother might still be able to save her child from harm: catch-ing the baby before she rolls off the bed, jumping after a toddler into a pool, yank-ing a distracted child back from the street. As we pull away, I imagine my mother feels the rescue distance between us like an invisible rope, just as I feel it with my own children—tightening, tightening, then breaking.

Women online talk about “mom guilt” and flagellate themselves for the occasional “selfishness” of attending to their own wants and needs. But when I hear selfish, I think selfhood.

Our plan is to ride along the Devil’s Backbone, a limestone ridge running from Wimberley to Blanco through the Hill Country. Neither of us has ridden this route before, and the novelty is part of the appeal. So, to me, is the lore.

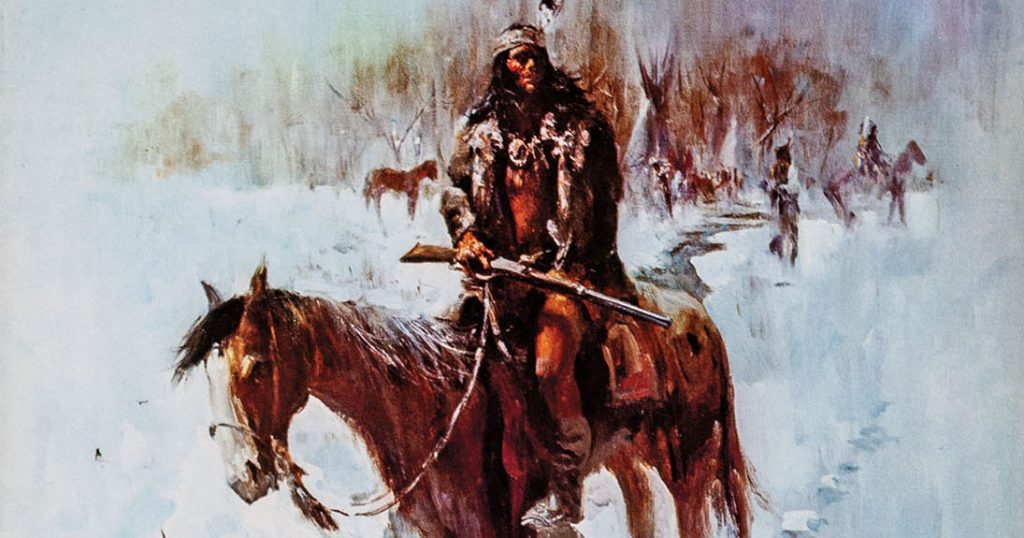

The Devil’s Backbone is considered one of the most haunted places in Texas. Before his death in 2010, author Bert Wall had lived among the ranchland of the Devil’s Backbone for 35 years. He’d heard stories about a wolf spirit that possessed people but didn’t believe them until his son went hiking with friends in an area known as the “Haunted Valley.” One of the boys saw a vision of a wolf jumping at him, and then the boy began “rant-ing in a language that sounded like a mix of Spanish and Apache,” talking about Comanche and Lipan Apache massacres.

Then there are the horses. Multiple people, including Lynn Gentry, Wall’s foreman, and rancher Charlie Beatty, have claimed to hear a stampede of hooves in the night. Gentry says the noise shook his cabin, waking him, and that when he went outside, he saw at least 20 horsemen who appeared to be Confederate soldiers. Meanwhile, on Purgatory Road, drivers have reportedly been thrown off course by an apparition on their hoods.

On the warm November morning of our trip, the sky is a vast uninterrupted blue. Today we’re riding Adrian’s sports bike, a Triumph Speed Triple R, which is leaner than the Tiger, with no back box to rest against or steel handles for gripping. Even 30 mph feels fast after three years away from the bike. I cling to his waist, interlacing my gloved fingers, but I’m grinning, welcoming back the wind between us.

From US 281, we take Farm-to-Market Road 1863 until it turns into FM 3159, or Cranes Mill Road. The landscape is hilly and green, rolling vistas shot through with surprising tufts of scarlet. The fresh air is occasionally cut with the smell of roadkill: squirrels and opossums but once also a buck, and I wince away from its sharply angled antlers. The dead animals remind me of the risk we are taking, a burden I carry like a child on my back.

We skirt Canyon Lake via FM 2673, then make a right onto FM 306. Eventually we turn left onto Purgatory Road, and here we encounter the hearse, shim-mering in the sun. There is a pause like a breath as we pass each other—the living and the dead. Seemingly nothing could be more appropriate.

After we pass the hearse, we’re alone on the narrow two-lane road. In some sections it’s buffeted on both sides by live oaks and mesquite, and on others it opens wide into yellow ranchland, the kind that looks unchanged by man or time. At night, beneath the weak silver light of a waning moon, Purgatory Road might be spooky and dangerous, with a small margin of error for drivers. But right now, beneath the swimming-pool-blue sky, the road is guileless, and it is ours.

We set an easy, cruising pace, and the wind in my helmet is like the ocean within a conch shell. All my senses coalesce on this particular place and time: the feeling of my arms around Adrian, the capable gloved ridges of his knuckles on the handlebars, the intimacy of communing without speaking. A wave of calm laps over my mind, soothing it after so many tense pandemic months and sleepless newborn nights.

We take Purgatory Road until we intersect with RM 32. Immediately to the left is the Devil’s Backbone Tavern, where before the pandemic I would have stopped to see if we could hear any ghost stories firsthand. The Tavern’s first stone room was built in the late 1890s on a Native American campground, and nearby a Civil War battle is said to have played out on the Devil’s Backbone’s limestone ridge.

A little farther down RM 32 is the Devil’s Backbone overlook, a grassy picnic area with a chain-link fence studded with crosses. They are wooden and woven, threaded with beaded rosaries, decorated with flowers, some faded to disrepair. Beyond, the view is rugged and wild and inhospitable, with a hazy blue line behind the hills and rock formations giving the strange illusion of the sea.

We turn around to take RM 32 to RM 12, heading into Wimberley. Due to the pandemic, we haven’t eaten out since March, but we’ve decided to have lunch at The Leaning Pear, a larger restaurant with patio dining slightly away from downtown. Tables are set appropriately apart, but each one is taken, and I feel conflicted as we settle into our meal. On the one hand, this small semblance of normalcy—pizza on a shaded patio, a mild breeze, laughing strangers—brings a surge of joy to my chest. On the other, it feels like being here, pretend-ing normalcy in the pandemic age, is the biggest and least justifiable risk of all. I find that I’m anxious to be back on the bike, just the two of us and the wind.

A wave of calm laps over my mind, soothing it after so many tense pandemic months and sleepless newborn nights.

After lunch, we return to RM 12 for a short ride to Jacob’s Well, a perennial karstic spring flowing from the Trinity Aquifer into Cypress Creek, accessed by a set of slippery stone steps hardly wider than my shoulders. The sun beats down on our heavy riding gear as we stand in the center of the concrete weir, built in the 1950s to prevent gravel from filling the well during heavy rains. On both sides of us, the emerald creek is a mirror of branches, leaves, and sky, with a thin film of algae skimming the surface. And just below us, like a massive fist has punched through the earth, is Jacob’s Well.

At 12 feet in diameter, Jacob’s Well is the eerie, mysterious entrance to an extensive underwater cave system that has intrigued divers for nearly 100 years, since a group of young men used a rubber hose and an empty milk bucket as a make-shift helmet. In 2007, the Jacob’s Well Exploration Project formed in an attempt to map out the network. It found the well drops 30 feet below the surface before the central passage branches off into two tunnels, one roughly 4,500 feet and the other about 1,500 feet.

Peering into Jacob’s Well is humbling, disorienting. It fills me with the hypnotic curiosity that I expect has consumed everyone who’s made the dive, including the dozen over the years who never resurfaced. It’s a reminder of that most human impulse: the desire to know. To discover what lies beyond what the eye can see, no matter the risk.

I leave the visor of my helmet cracked open as we travel from Jacobs Well Road to Fischer Store Road. Like Purgatory Road, the former is narrow and two lanes, and we’re the only people for miles. The wind on my face is warm and affirm-ing. Something in me has shifted. I’m no longer thinking about death but about life. The pandemic has taken the most joyful things about living away from us, but today we’ve managed to steal one of them back—time with each other, outside our home and away from the relentless demands of parenthood. Like it always has, the bike has connected us.

Fischer Store Road is the curviest one of the day. I’ve finally found my equilibrium on the bike—my hands are no longer locked together but resting, relaxed, on Adrian’s waist, as we cross over the Blanco River. Then we connect again with RM 32, meandering around Canyon Lake via FM 306, before taking FM 2673 to River Road.

Here, we ride parallel to the Guadalupe, catching glimpses of clear water through brilliant swatches of color—leaves of saffron, russet, chartreuse. We park and walk alongside a stretch of river. There are no kayaks, no anglers in rubber waders, no picnickers. It’s just Adrian and me, the river, the quiet. We’re laughing and holding hands, both of us lighter than we’ve been in months.

Eventually we return to the bike, and I text my mom that we’re heading home. I’ve texted her at every stop, aware in a way I wasn’t before having children how much she needs that reassurance of our safety, and how easy a gift it is to offer.

As we begin our final stretch, my breasts feel bruised with milk every time my chest nudges Adrian’s back. Both children should still be napping. I picture them in their cribs: Jo, at 2 1/2, belly down on three fuzzy blankets, a dozen stuffed animals piled at her feet; and Jack, 2 months, snug in the swaddle it took us so long to get right, lips in a contented half-smile, as if he’s rolling a good memory like candy in his mouth.

Is the risk we took worth it? I don’t know. But I feel that familiar blend of wildness and peace that comes from riding. I feel like my whole self—not just a mother, not today—and also relieved as the distance between my parents, our children, and us closes.

Ten minutes from home, behind the Kevlar of my jacket, my milk lets down.