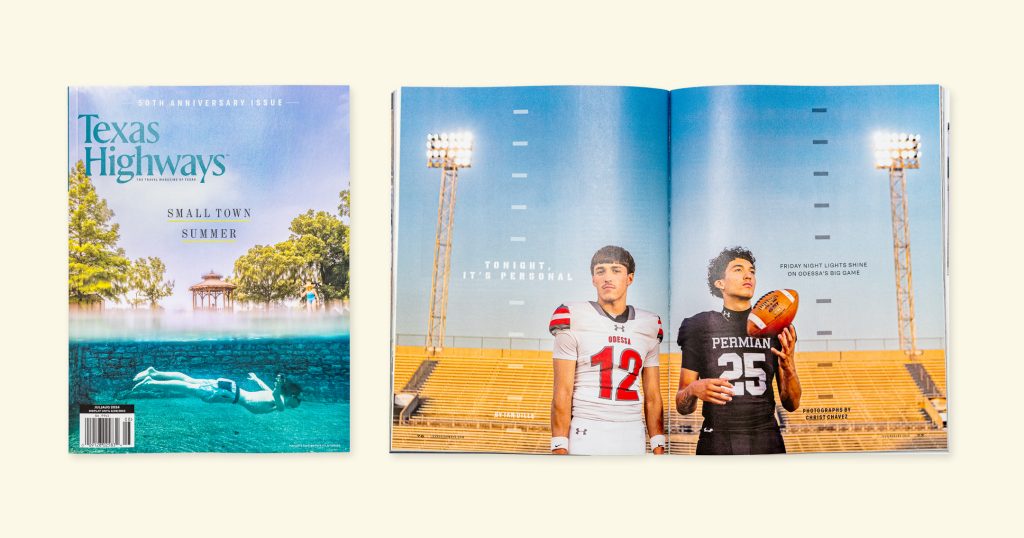

Soaring to 1,022 feet, the Waterline will become the tallest tower in Texas when it opens in 2026. Rendering courtesy of Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates.

The recent announcement that construction will soon begin on Texas’ tallest skyscraper came as a surprise to many. Not necessarily for the structure itself, but where it would be built—in Austin, not Houston or Dallas. It’s a sure sign the capital city has joined the civic competition to erect the tallest building, and therefore claim the title of tallest city in the Lone Star State.

That urge to be tallest has played out among civilizations since the pyramids rose in Egypt and Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize in the Americas.

Cathedrals in Europe and the United States competed to be the tallest for several hundred years until the late 19th century, when structures like the 548-foot-tall Philadelphia City Hall, the 555-foot-tall Washington Monument, and the 984-foot-tall Eiffel Tower vied over who could be the tallest in the world.

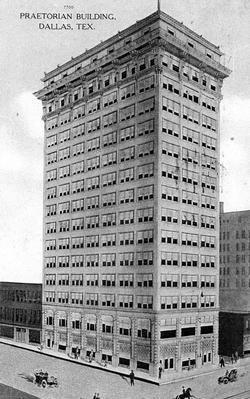

The Praetorian Building, from a 1908 postcard.

Texas got into the skyscraper game relatively quick, in 1908, with the opening of the 15-story, 190-foot-tall Praetorian Building in Dallas (which was torn down in 2013). Houston could already brag about the eight-story First National Bank Building (completed in 1905). Designed by Sanguinet and Staats, the architectural firm responsible for many of Texas’ tall buildings in the early 20th century, the structure later became the Lomas and Nettleton Building. (Located at Main Street and Franklin Avenue, it houses residential lofts today.) By 1910, Houston also had the 10-story, 124-foot-tall 711 Main Building and the 23-story, 302-foot-high Carter Building, allowing Houston to claim the title of Texas’ Tallest City.

Two years later, the honorific returned to Dallas with the opening of the 25-story Adolphus Hotel, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this month with a gala on Oct. 29. In 1925, the Adolphus gave way to the Magnolia Building, as Dallas’ (and Texas’) tallest with the Magnolia Oil Company’s neon flying horse logo atop the 399-foot, 27-floor edifice. (It was recently announced the building will undergo a major renovation, including the addition of three floors.)

Houston regained the tallest title in 1927 with the completion of the 410-foot, 31-story, Italian Renaissance-styled Niels-Esperson Building, followed two years later by the 37-story, 428-foot art deco Gulf Building. Houston managed to hold on until 1943, when the Mercantile National Bank Building, a 31-story, 523-foot-tower with a distinctive clock spire opened in Dallas.

The back-and-forth rivalry between Dallas and Houston continued for another 40 years:

Dallas – Republic National Bank (1954; 36 stories, 602 feet)

Houston – Humble Building (1963; 44 stories, 606 feet)

Dallas – First National Bank Tower (1965; 52 stories, 628 feet)

Houston – One Shell Plaza (1970; 50 stories, 714 feet)

One Shell was still a tad taller than Dallas’ new tallest, the 56-story, 710-foot-tall First International Building, built in 1974. But by the time the 74-story, 921-foot Bank of America Plaza was completed in 1985—the tallest skyscraper in Dallas—Houston had one-upped its main competitor again with the 1,002-foot, 75-floor Texas Commerce Building, now named the JP Morgan Chase Tower, which has held the Texas’ Tallest title since it was built in 1982. Whew!

That honorary is about to change, and this time neither Dallas nor Houston is in the race. Enter Austin.

The capital city came late to the tall skyscraper game. Until 1974, the Texas State Capitol (standing at 302.64 feet “from the south front ground level to the tip of the star of the Goddess of Liberty”) reigned as Austin’s tallest building, mainly because the city enacted an ordinance to keep it the predominant building in the city’s skyline. It was complemented by the 29-story, 307-foot-tall University of Texas Main Building (aka The Tower), followed in 1972 by the Dobie Center, also on the UT campus and 307 feet. By the mid ’80s, Austin had more than a dozen skyscrapers, with 600 Congress leading the pack for tallest for 20 years before the 515-foot Frost Bank Tower arrived in 2004.

Meanwhile, construction pretty much came to a halt in Dallas and Houston. Big D stopped aspiring for higher heights, settling for new towers in the 30- to 40-story range until the 42-story Museum Tower broke through in 2013. And, after reaching its zenith in the 1980s, Houston experienced fallout from the Savings and Loan economic meltdown, followed by the Federal Aviation Authority’s mandate prohibiting construction of buildings taller than 75 floors in the central business district because it is in the takeoff and landing flight patterns for Hobby Airport. Outside of downtown, no significant towers have been built since the 64-story, 901-foot Transco Tower near the Galleria opened in 1982.

Fast-forward to Austin around 2010, when residential and tech started dominating the local skyscraper boom. More than 20 steel-and-glass towers have been built, topped by the current city champ, the Independent (aka the “Jenga tower“), at 58 floors and 690 feet, and the 56-floor, 683-foot Austonion, with its distinctive crescent top.

Why the sudden high-rise boom? “I would suggest the reason why they are taller in Austin is because it is so physically small and so dense,” says Mark Lamster, the architecture critic for the Dallas Morning News who teaches architecture at the University of Texas at Arlington and is a Loeb Fellow of architecture at Harvard. “That means the land is incredibly valuable, and that makes it financially desirable to build extremely tall.”

Also, skyscrapers in Houston and Dallas tend to focus more on style than height. “There isn’t an emphasis on being the ‘tallest’ because buildings are now developed by investment groups rather than individuals or companies, for whom the ‘tallest’ moniker might be appealing,” he says.

Pennzoil Place. Photo by Agsftw, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Lamster cites Pennzoil Place in Houston, still one of the state’s most revered skyscrapers, as an example of style over stature. “[Then Pennzoil CEO] Hugh Liedtke, who commissioned the building specifically, did not go for ‘tallest’ because he knew that there would always be some other building to eclipse it,” he says. “So Pennzoil Place focused on quality and distinction [rather than height]. That worked.”

So, in Austin, the rise to the top goes on. Both of the city’s tallest buildings will be eclipsed next year by a residential and office tower being built at Sixth and Guadalupe streets and listed at 66 floors and 875 feet high. The building will have a primary tenant, the tech company Meta, parent of Facebook and Instagram. That’s plenty tall, but in a few years it will still not be Texas’ tallest.

That accolade will pass to the Waterline, a 73-story, 1,022-foot-tall residential-hotel-office tower at 98 Red River. Its scheduled completion date is mid-2026. I know the location well. The site was formerly occupied by a funky two-story white clapboard boarding house where I rented a cheap office for $80 a month back in the 1980s. That was Old Austin. The future occupant is New Texas all the way—shiny, bright, and rising to the skies.

Will this be the apex for Texas skyscrapers? Given its history, odds are taller towers are coming. And the short answer as to why is “money,” Lamster says. “Or, as Carol Willis, the historian and founder of the Skyscraper Museum puts it, ‘form follows finance.’”