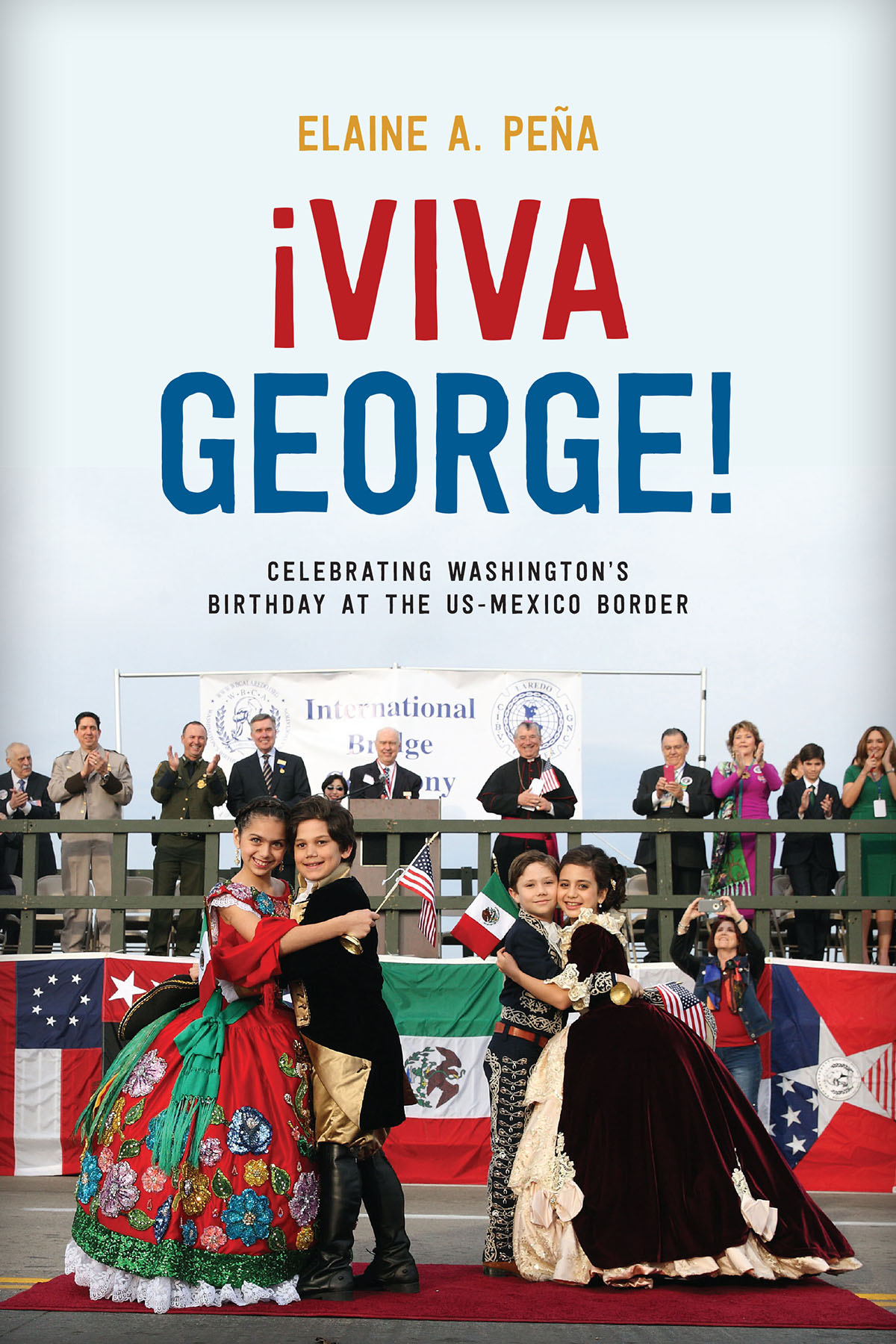

The cover of ¡Viva George!

Laredo may seem a bizarre place to stage a recreation of the Boston Tea Party, but the spectacle has been part of the city’s history since 1898. Volunteer actors toss candy in lieu of tea from the deck of a wooden ship built for the occasion, while thousands of attendees from both sides of the border cheer them on.

The Tea Party is a part of Laredo’s annual Washington’s Birthday Celebration (WBC). As a child, Laredo native Elaine A. Peña was in equal measure fascinated and confused by some of the events, which seemed incongruous in a border town like Laredo. Now an anthropologist and associate professor of American Studies at George Washington University, Peña unravels the complex ethnography and origins of Washington’s Birthday Celebration in her new book, ¡Viva George! Celebrating Washington’s Birthday at the US-Mexico Border.

The revelry, which takes place every February and can last up to a month, features reenactments, parades, a Princess Pocahontas pageant, live music, a Society of Martha Washington ball, a carnival, and a jalapeño-eating contest. (Updates for next year’s events can be found here.) The celebration culminates in an emotional bridge ceremony that brings together residents from Laredo and Nuevo Laredo for an embrace at the middle of the World Trade International Bridge. It is, Peña says, the single most important event, a symbolic putting aside of political and cultural differences.

Here, Peña shares the cross-cultural dynamics of Washington’s Birthday Celebration and how such border events can be useful tools for helping adjacent nations navigate and mitigate crises and maintain international relationships.

How did WBC start?

It began with a fraternal organization of white colonists, the Improved Order of Red Men (IORM), in 1834. Their goal was to remind people that the soil under their feet was indeed part of the United States, not Mexico. Laredo was but one of several locations in Texas where they established “tribes,” but it’s the only place where activities were carried out with cross-border considerations. It’s also interesting to note that most boosters were naturalized citizens from Europe and Canada, which puts an interesting spin on patriotism. Certainly, no one would ever have expected George Washington to be celebrated with such gusto in Laredo, of all places.

What motivated you to write this book?

Growing up, I had so many questions about WBC because what I was seeing enacted didn’t fit what I’d read or generally knew about Native American culture and history, nor was it reflecting their traditions. I wondered why Pocahontas was being celebrated and why a bunch of different tribes like the Sioux and Comanches were being portrayed with such elaborate costumes. Racial and social justice issues weren’t really front and center at the time, and never discussed in the context of the festivities. While still drawn to the celebration, my unease never really dissipated, so I decided to write a book about it.

Is it fair to say ¡Viva George! is essentially a distillation of the symbiotic relationship inherent to shared borders?

I’d call it an opportunistic symbiosis. It’s ultimately about the port’s shared economic advantage—it’s North America’s busiest dry port and ahead of both New York and Los Angeles in terms of trade. Countries with shared borders must learn to work together when natural disasters strike and to combat drug-war or other violence. Border celebrations are practiced throughout Texas and worldwide, because they serve as a tool for communication in times of crisis. … It’s a way for border communities to maintain family, religious, and economic ties between populations and celebrate them with pomp and circumstance, no matter what broader political messages convey about the border.

How did WBC become the cross-cultural event it is today?

Since the 1930s, it’s featured reenactments and traditions from both countries like recreating Xochimilco [site of Mexico’s famed floating gardens] in Laredo’s central plaza and hosting a Noche Mexicana. By that era, WBC had grown so large that the IORM could no longer manage the logistics alone, so they had to go to the Laredo City Council for help. By then, it was simply impossible to contain an American identity in a cross-cultural environment.

The celebration also gave birth to the paso libre, correct?

Yes, that’s the most important thing in this book. After Hurricane Alice destroyed the [International Bridge in 1954], there was vested interest from both the Mexican federal government and the City of Laredo to get it rebuilt as quickly as possible to protect trade interests. The opening of the new bridge was delayed due to management discrepancies, so Laredo officials decided to time a paso libre [free pass] with the WBC as a way to negotiate tensions. For three days every year, through the early 1970s, Mexican citizens were issued tourist visas and permitted free movement across the border, even if they lacked documentation. Sadly, since 9/11, things are different and border control and immigration in general have had to become more stringent, but it’s also important that we learn to approach border politics in a way that is conducive to the well-being of either country and its residents. It shouldn’t be about dehumanizing them.

Why is Washington’s Border Celebration relevant in the grand scheme of things?

This idea of border reenactments, where people come together from both sides in a ritualistic way to meet face to face, is critical—it humanizes the border in ways that don’t reinforce derogatory stereotypes. Borders are important—they’re the material evidence of sovereignty. But the way they’re overly politicized by respective federal governments, who in this case are far away, hurts the people on both sides.

Where did the book’s title come from, and what do you hope readers take away from reading ¡Viva George!?

I chose the title because it’s tongue-in-cheek, but it’s also appropriate for a book about trans-border, cross-cultural relationships. My hope is that we can all make better decisions moving forward about resolving our border dispute, but it’s also a cautionary message on a broader scale: How do we remember our past, if we pick and choose what to remember? It’s not as simple as just meeting in the middle of a bridge to embrace, but to plan that meeting in advance, to keep lines of communication open.