“The Wild Sounds of New Music” heavily influenced J D Emmanuel’s creative direction. Photo by Cameron Kelly McLeod, Courtesy ISSUE Project Room

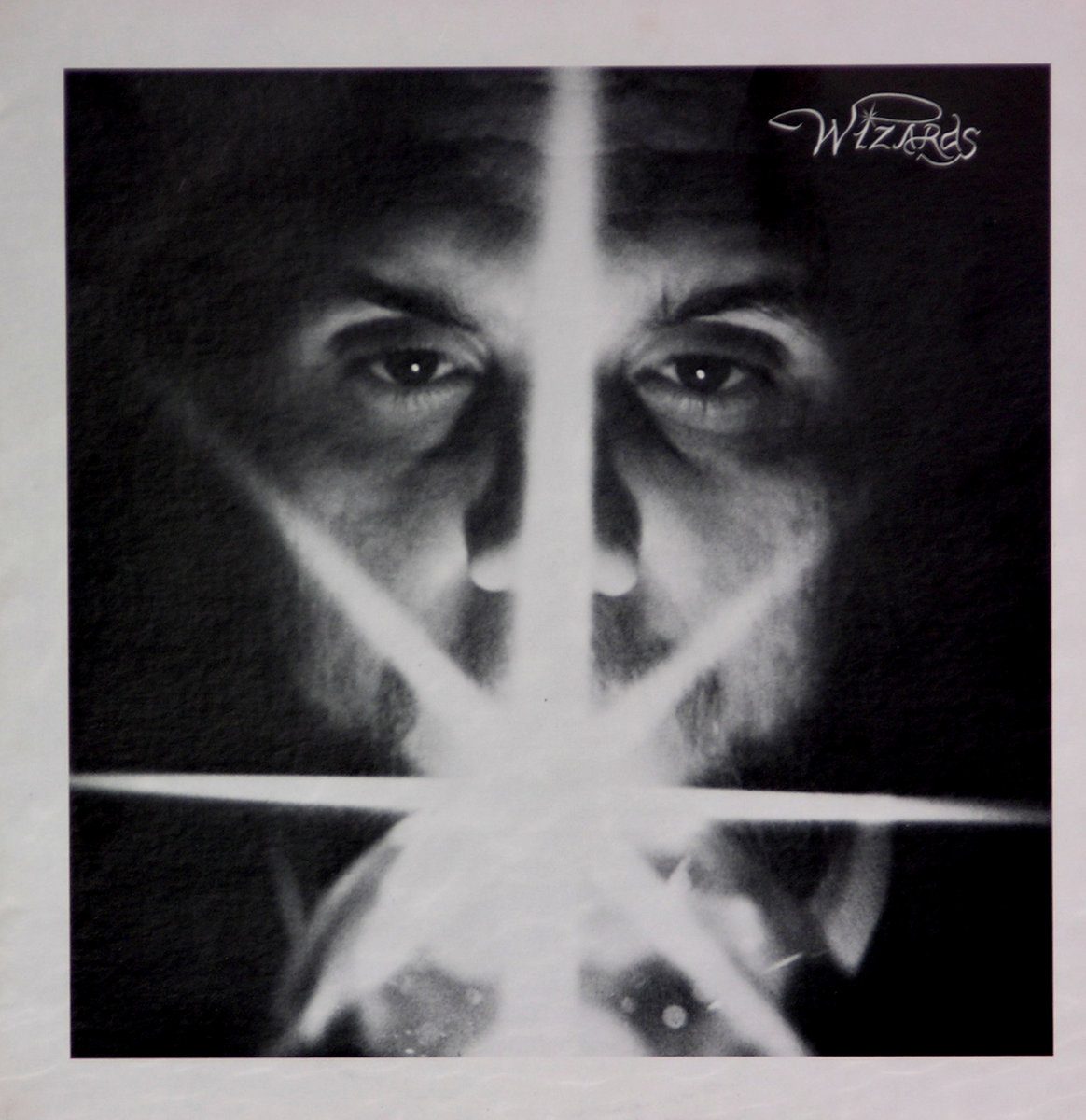

To listen to J D Emmanuel’s 1982 album Wizards, considered a standard of New Age and minimal electronic music, is to be swaddled in synthesizer. The tracks are repetitive and sympathetic, and focus on slowing the listener’s mind. It’s experimental music developed not in the serious music scenes of New York or San Francisco, but in the confines of his Texas home. The songs Emmanuel has created over 40 years started as a personal bridge to explore meditation, and while they remain linked to meditative states, Emmanuel has increasingly used his music as a vehicle for expressing his appreciation for esoterica.

Minimalism, as a post-WWII art movement, was pervasive in visual art, architecture, and even furniture design. In the ’60s, budding jazz and classical composers like Terry Riley and Steve Reich began applying the minimalist aesthetic to their music as well as experimenting with synthesizers, drone, and tape loops. These are the seeds of minimal electronic music. Both composers are influential on Emmanuel’s music, but Emmanuel’s pedigree is quite different.

Riley is from northern California, a cultural epicenter, and studied at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and Berkeley, and Reich, the son of a Broadway lyricist and singer, was born in New York City and studied at Cornell and Juilliard. Meanwhile, Emmanuel started out life in the small town of Joaquin, the son of two school teachers, and when he felt unfocused at the University of Houston and later Blinn College, he dropped out and started a career in sales.

In spite of this, Emmanuel, now 71 and living outside of Houston, in Shenandoah, became a master of meditative music. He is mentioned in the same breath as other minimal, experimental, and New Age pioneers. In the early ’80s, when most Texans were listening to ZZ Top or Willie and Waylon, Emmanuel was toying with field recordings of rainstorms or birds at the Houston Zoo, and overlaying syncopated tape delays with improvised synth. While some may not hear “Texas” in Emmanuel’s songs, I think his individualistic spirit and commitment to exploration fit right in.

J D Emmanuel’s 1982 album “Wizards” is an exemplar of minimal electronic music. Courtesy J D Emmanuel

How were you introduced to meditation?

Emmanuel: In 1970, I was in Houston and my next-door neighbor, Tommy, said you’ve got to hear this thing I taped off the radio. It turned out to be a gentleman named Richard Alpert, aka Ram Dass. He was buddies with Timothy Leary and Aldous Huxley, and he talked about how he went on a journey and ended up in India, where he met a guru who blew his mind and taught him about how to go to the next level. I never forgot that. I’ve still got the full recording, a delightful three-hour lecture. I listen to it every once in a while.

One more element to add to this, when I was about 8 years old, I would purposely go to my grandmother’s bedroom. She had these very heavy drapes and I would lay down and go into these dream states using the drone of the air conditioner.

Following that, I discovered that my mom had this old Motorola mono turntable stereo. I would put on a record and it didn’t matter if it was West Side Story, Bach, rock ‘n’ roll. If it was something I liked, I could lay down, close my eyes, and boom, the album would be over. It took me away. That’s when I began purposely using music as the essence of my expanding consciousness. Of course, when you’re 8, 10, 12 years old, you don’t call it that. And all of that kind of was already in my brain, and it kind of affected my open-mindedness.

That is the fundamental essence of my relationship to music and meditation and things of that nature. I just kind of refined it as I got older.

When did you start practicing meditation?

Emmanuel: Right before Christmas in 1971, I moved from Houston to Atlanta because I worked for a company called Houston Blacklight & Poster Co. After I moved to Atlanta, I really got interested in meditation. Somehow, you kind of attract people to yourself, like a magnet. I met some people and went to classes and started understanding meditation a little better. One of the key things that I understood was the idea of having a mantra—a focus to help keep your mind from wandering too far off. A mantra isn’t anything special. People kind of make too big of a deal out of that. It’s whatever resonates within you. The ’70s was me developing that relationship, as well as continuing to evolve into the music that I would later create.

Did your family cultivate your interest in the esoteric and metaphysical?

Emmanuel: Zero [laughs]. We attended a community church, a nondenominational church. I had no special interests. I was a musician. I played the trombone and the bass trombone in the church band.

When did your interest in metaphysical subjects start?

Emmanuel: As far as actually getting into something like that, I always loved science fiction. In the summer before fifth grade, I got into the Edgar Rice Burroughs “Mars” series. I mean, I just ate those up, and they’re pretty rowdy [laughs]. I was strictly into Burroughs’ sci-fi, Ray Bradbury, and The Twilight Zone. I guess I was always fascinated by the unseen and the possibility of it.

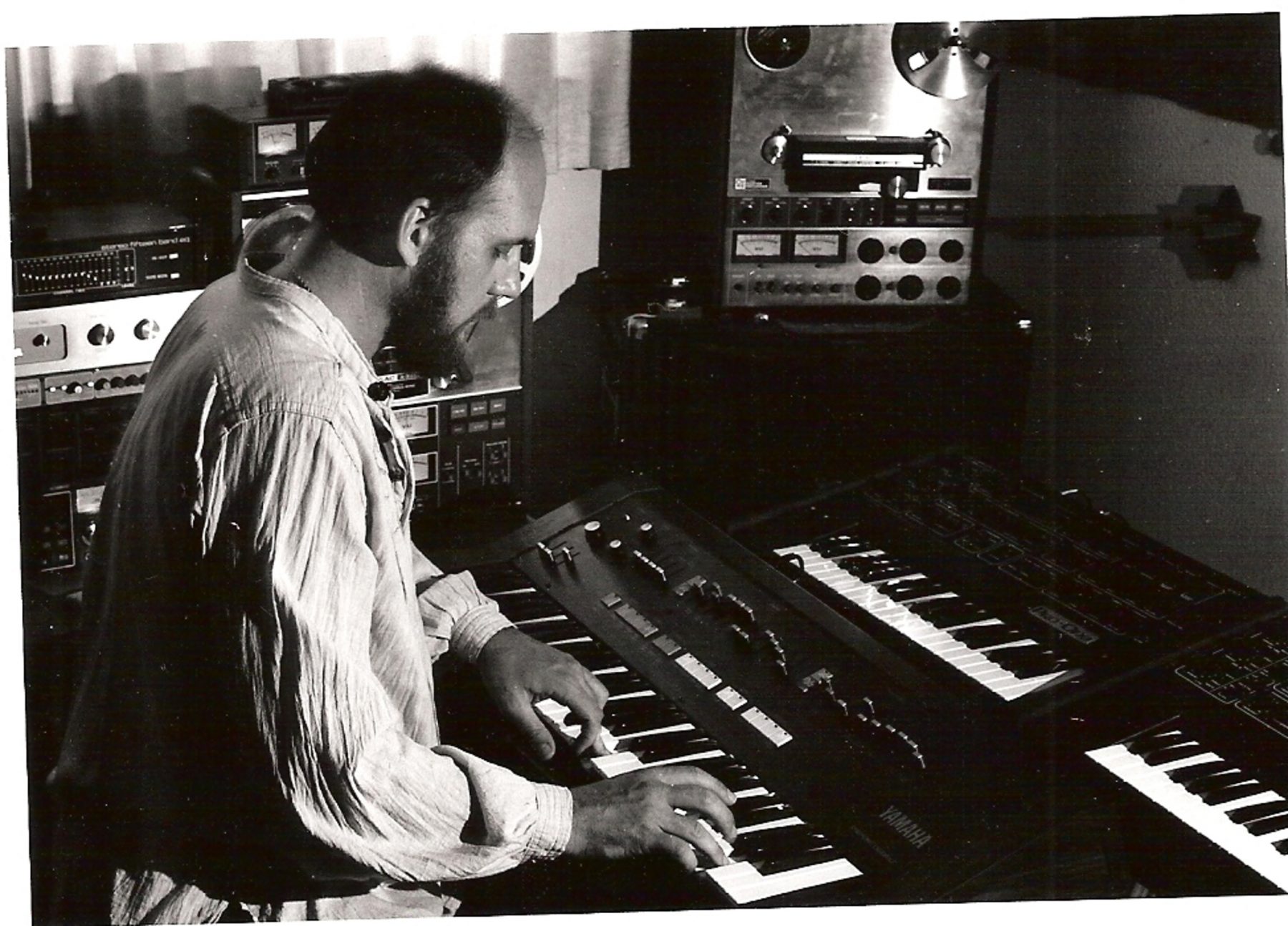

In the early ’80s, J D Emmanuel experimented with field recordings, and overlaid syncopated tape delays with improvised synth. Courtesy J D Emmanuel

How did you start experimenting with minimal electronic music?

Emmanuel: My music skills came from two different events. One happened in 1970 or so. My brother had loaned me the album The Well-Tempered Synthesizer and had left the sampler The Wild Sounds of New Music in there. On it were two tracks that took me to such a different place in music, I decided if I ever made music, that’s what I wanted to do. It was Terry Riley’s “A Rainbow in Curved Air” and Steve Reich’s “Violin Phase.” I immediately went and bought the full albums and wore them out. Again, at this time I’m still listening to rock ‘n’ roll and heavy into jazz—you know, Les McCann and Eddie Harris. It all had to do with the extended play—15- to 20-minute extended plays.

That kind of set the foundation for me to start trying to figure this out. Then in the summer of 1979, I read a book called Through Music to the Self by Peter Michael Hamel. He’s a very good electronic musician himself. In it he dissected the song “A Rainbow in Curved Air,” and I really got it. All of a sudden, I understood how I wanted to do it and what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to be like anybody. Hamel gave me the foundation of how to approach what I call “electronic minimal” music. I had a friend that had a 4-track reel-to-reel that he let me borrow, and I had just acquired a Crumar Traveler-1 organ. I also had my guitar and an Echoplex EP-4 for delays and loops. And that’s when I started my music experiment. I truly mean the term “experiment.” I just never know where it’s going to go.

In the beginning there was a utility to it. You were doing it for yourself.

Emmanuel: Oh, absolutely. 100%. You got it, man. The reason this was so important to me … as a little kid, I did have a problem—it’s what they would call ADD now. But we didn’t have that kind of stuff in the ’50s.

I was dealing with this restlessness. I needed to have something to focus and calm my mind, and the music and the meditation were perfect for it. When I figured out how to do this type of music, it was just for my soul, and then I thought I’d see if other people would like it, too. It turns out, over the years, they did.

Where else did you find influences in the middle to late ’70s, early ’80s Texas?

Emmanuel: On Pacifica Radio [in Houston] there was a radio show by a lady named Margie Glaser. I’ve got a bunch of her shows that I taped where she played Hans-Joachim Roedelius, Cluster, and Tangerine Dream. Again, I only had a few people that I knew that messed with that kind of stuff. I even had a guy that wanted to see if he could get my music into the club. Nobody wanted to do it because they called it “headphone music.” I tried to play two shows back then. One of them was for a music festival in Washington-on-the-Brazos, to raise funds for kids, called the Peaceful Kingdom concert.

Last year, J D Emmanuel performed at the First Unitarian Congregational Society in Brooklyn. Photo by Cameron Kelly McLeod, Courtesy ISSUE Project Room

What’s your current relationship with meditation?

Emmanuel: I do it several times a week and usually with music. I put myself in an altered state with deep, rhythmic breathing and tell myself I’m one with the universe.

Do you have any practical advice for someone who’s dealing with anxiety during the pandemic?

Emmanuel: One of the things that is the biggest enemy is your imagination. I learned this through becoming certified in Neurolinguistic Programming. You have to identify what you’re actually afraid of. One of the things I’m blessed by is having been able to find the essence of reality.

Back in 1978, around Thanksgiving, I went to an Erhard Seminars Training. One of my favorite things I learned there was “What is, is” and “What ain’t, ain’t.” Don’t get caught up with what ain’t. That’s the beauty of Zen. Right now is the only thing that matters. So, what do you need to do right now? Well, you need to go wash your hands, you need to go walk with the dogs. The best way to help yourself is to find some activity that you enjoy, something that you can creatively get involved in. I remember reading something once that said, “See where your mind goes, and don’t follow it.”