Drought conditions led to the discovery of new dinosaur tracks near Glen Rose. Photo by Paul Baker, courtesy Friends of Dinosaur Valley State Park.

Millions of years ago–113 million years ago to be more exact—before the Paluxy River flowed through limestone hills, the town of Glen Rose was a vast and shimmering mud flat on the shores of the inland sea. The flats were a highway for Central Texas dinosaurs, including vast, long-necked sauropods and swift-stepping predators. The mud recorded their tracks; successive layers of silt covered and petrified them, carrying them down through the millennia to the modern day.

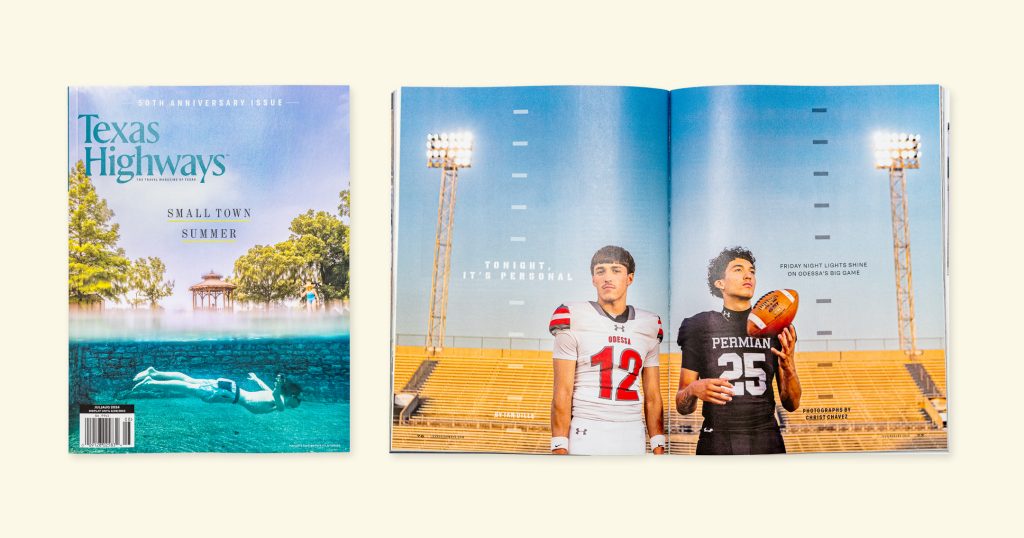

The resulting trackways have been a fixture of Texas paleontology for over a century, and the centerpiece of Dinosaur Valley State Park. Every year, visitors arrive from all corners of the state to swim in the river and walk in the footsteps of dinosaurs. This year, on the park’s 50th anniversary, that’s easier than ever: As the Paluxy has dried due to drought, it’s revealed trackways usually hidden by the water.

“It’s not a good thing for the river, but it’s great for people who want to research tracks,” says park superintendent Jeff Davis. For two months, the park received no rain, and staff watched the river shrink in its bed, eventually revealing the faint shape of immense, birdlike feet. “We jumped at the opportunity to go out and clear off these tracks.”

The revealed trackway, nicknamed the Lone Ranger, records a moment in time when an immense predator dinosaur cruised down the mud flat on some unknowable errand. The identity of the track maker isn’t entirely clear—you can’t discern a species identification from footprints—but they likely belonged to Acrocanthosaurus, a long-jawed hunter whose fossils are well known from nearby geological formations. “Unless we find good specimens somewhere nearby,” Davis says, “we may never know for sure.”

The carnivore tracks found at Glen Rose are just a sampling of what the site has to offer. Glen Rose is also famous for its sauropod tracks, including massive footprints likely left by the 60-foot-long, 40-ton titan Sauroposeidon. “We have some of the best sauropod tracks in the world,” Davis says. “Usually they’re just sort of round, but on ours you can see individual toes and claws.”

The tracks are visible due to the natural erosion of the Paluxy, as it cut through the surrounding limestone and revealed the hidden trace fossils. Native Americans living in the area must have seen them, Davis says, though they left no oral or written records of it. The descendents of European settlers first discovered them in 1908, and they immediately became a big hit, particularly during the Great Depression. In the 1930s, paleontologist Roland T. Bird collected a long stretch of sauropod tracks and shipped them up to the American Museum of Natural History, where they remain to this day. Still others were carved out and sold privately. Finally, in 1972, Dinosaur Valley State Park opened to protect the area’s prehistoric riches.

“There’s definitely a lot more tracks under the prairie than we may ever see,” Davis says.

The river might have excavated the long-buried tracks, but it also holds them at its mercy: high waters can cover them, and floods occasionally wash away whole sections of ancient footprints. Tracks in more protected areas have lasted for decades, and might last for decades more, Davis says, but there are no guarantees, save that eventually, inevitably, the tracks will weather away.

Sites like the Lone Ranger Trackway and the Billy Paul Baker Site are generally only exposed when the river is very low. It’s been two decades since the last time the Lone Ranger’s movements were visible, according to Davis: Usually, they’re covered by gravel bars and deep water. This time, park staff went out with dowel rods to break up the dried sediment and remove the rocks. They used a leaf blower to sweep the dirt away, leaving the perfect set of tracks revealed in the rock.

The uncovered trackway has been drawing visitors from across the state after an extremely quiet summer, Davis says, and it’s a great time to come out and look at some of the best dinosaur tracks in America. But Davis wants to remind visitors that the tracks are fragile. “We want people to look at them, enjoy them and photograph them, but once they’re gone, they’re gone,” he says. “And it’s important that people protect and conserve them.”