Mack McCormick (right) photographed with drummer Spider Kilpatrick. Photo courtesy National Museum of History Archives Center, Robert Mack McCormick Collection, 1485, Box 10, Folder Photographs of Mack McCormick, modern, 1960-1998, undated

The first time I saw Mack McCormick’s name, it was attached to the liner notes on the back of the first albums issued by Arhoolie Records, the storied American folk music label founded by Chris Strachwitz. At the time, I didn’t know McCormick had led the Polish-born music enthusiast, who passed away earlier this year, to Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mance Lipscomb, and Clifton Chenier—Arhoolie’s core artists—before falling out with him. The break was a familiar pattern for Mack McCormick, as I came to learn.

Eight years after his death in 2015 at the age of 85, the self-taught music folklorist and field researcher from Houston is finally having his moment. The Smithsonian Institution has recognized Robert “Mack” McCormick with a book, an exhibit, and, coming Aug. 4, a box set of 66 field recordings he made that are nothing less than the most comprehensive collection of Texas blues music ever assembled.

McCormick was a high school dropout who held a series of odd jobs to underwrite his passion—collecting, recording, and writing about music from what he called “Greater Texas,” East Texas and surrounding states extending back to Mississippi. He was particularly fond of African American blues. From the 1950s through the 1970s, he traveled throughout Texas and the South searching the places where early recording artists and their music originated and seeking out the music makers and people who knew them. For McCormick, it was all about the hunt for music and information, which he rarely shared, even while he dealt with personal issues including anger and isolation and clinically diagnosed manic depression.

As a field researcher chasing music, McCormick was directly influenced by John Avery Lomax and his son Alan Lomax, the trailblazing song hunters and music folklorists who were also from Texas. Lomax’s eldest son, John Avery Lomax Jr., and McCormick were both involved with the Houston Folklore & Music Society, founded in 1951, which nurtured the careers of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Mance Lipscomb, Townes Van Zandt, Nanci Griffith, and Guy Clark.

Unlike the Lomaxes, who were tied to academia and the Library of Congress, McCormick was an amateur obsessive. To support his habit, he drove taxis and worked for the U.S. Census Bureau in Houston’s Fourth Ward in 1960, just so he could learn more about barrelhouse pianists in the neighborhood. In addition, he did contract work for the Smithsonian in the late 1960s and early ’70s, scouting the South for talented musicians to perform at the institution’s summer music festival.

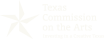

Mance Lipscomb with his family, photographed by Mack McCormick. National Museum of History Archives Center, Robert Mack McCormick Collection, 1485, Box 20, Folder 17, Outsize photos, Texas Blues, undated

Of all the musicians McCormick studied, none captured his attention more than Robert Johnson. In May, the Smithsonian published McCormick’s much-anticipated Biography of a Phantom: A Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey about the influential Mississippi Delta blues guitarist and singer who once recorded 42 songs at sessions at the Gunther Hotel in San Antonio in 1936 and the Warner Brothers/Vitagraph building in Dallas in 1937 before dying in 1938, allegedly under shady circumstances. He would become a major influence on Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and other British rock guitarists of the 1960s, and one of most mysterious figures in blues music.

Twenty years after Johnson’s death, McCormick started chasing Johnson’s ghost. Studying phone books and maps and making cold calls, he drove all over Mississippi following leads, visiting neighborhoods, asking around. McCormick’s manuscript about his quest was first finished in the early 1970s, but he continued making revisions without ever publishing it. After McCormick’s death, John W. Troutman, curator of music and musical instruments at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, edited the manuscript and wrote the book’s detailed preface and afterword.

Here’s my suggestion to truly appreciate Biography of a Phantom: Skip Troutman’s commentary until later, forget you’ve ever heard anything about McCormick, and dive in.

It’s a fun ride, part detective mystery, part anthropological travelogue. McCormick’s research methodology may seem quaint and dated, but it led to opportunities for direct contact: He speaks with relatives and friends who knew Johnson very well—and under another name. As the hunt progresses, McCormick’s appreciation of the secondary characters as real people changes, and he understands the artist more in the context of the community he lived in, culminating in a vivid scene in 1970 in a Mississippi Delta shotgun shack, where the music so familiar to his friends and family is played back to them on recordings.

John A. Lomax’s Adventure of a Ballad Hunter is the template for all books about collecting music. Other books, such as Where Dead Voices Gather by Nick Tosches and Do Not Sell at Any Price by Amanda Petrusch, do deeper dives into that obsessive world, but Biography of a Phantom hits the sweetest spot. It shines the light on the music chase at a time when scores of collectors were fanning out to the countryside trying to find out about a blues song’s origins or a recording artist’s roots.

McCormick’s friend Roger Wood, author of the books Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues and Texas Zydeco, says the published manuscript reminded him of John Graves’s Goodbye To A River. “[I]t takes the reader on a very personal trip with the narrator, who intertwines history and immediate experience, prior knowledge, and discovery, to communicate how a place, a culture, has changed over time (and will change more in the future),” he tells me in an email exchange. “I see/appreciate this book as great writing, the most fully articulated presentation of Mack’s narrative voice and capacity for engaging his audience.”

Wood adds, however, that McCormick would have hated it. “Mack would likely be furious about myriad details and developments with this [or any] publication beyond his control and the process that led to it,” Wood says. “He would likely threaten lawsuits, claim victimhood, add several new names to his enemies list, etc. Even if he had consented to whatever transpired, he would likely be furious, if not immediately, eventually—after he had taken time to sprout and nurture grievances. That was Mack.”

With fury and resentment no longer impediments, the story that finally has come out stands on its own merits. It’s a quest that anyone who has loved a particular song or artist can relate to. For blues researchers and scholars, this is as deep as the hunt for music ever gets.

When doing his field research a half century ago, McCormick knew he would draw scrutiny of white law enforcement and Black community leaders, but he jumped the color line nonetheless, a brazen act at the time. A Black researcher chasing white music could not have done the same. This reality is addressed in Treasures and Trouble: Looking Inside a Legendary Blues Archive, the exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of History opened in June in Washington D.C.

For Texans unable to travel to the nation’s capital, the exhibition showcases artifacts from “The Monster,” McCormick’s nickname for his massive collection of work, along with a reexamination of the process of gathering and preserving music. There is a focus on the patriarchal dynamic of a white man documenting a Black man’s history in the Jim Crow segregated South, and a frank assessment of McCormick’s myriad issues, which included grifting and hoarding.

McCormick persuaded Johnson’s siblings and heirs to share photographs and stories and sign agreements to share in profits from his estate, but he did not return materials to the relatives, as letters in the exhibit document. A Memphis producer named Steve LaVere subsequently secured an agreement from Johnson’s half-sister Carrie Thompson that effectively undercut McCormick. He wasn’t the only music hound chasing Johnson’s ghost, and the realization that he might not be able to capitalize on his quest might have contributed to McCormick’s fragile mental state.

McCormick preserved critically important music and information about African American musicians in the early and midcentury, and how he went about it is rightfully called into question. Certainly, what he did then is not what someone could do today. Then again, what they were chasing no longer exists.

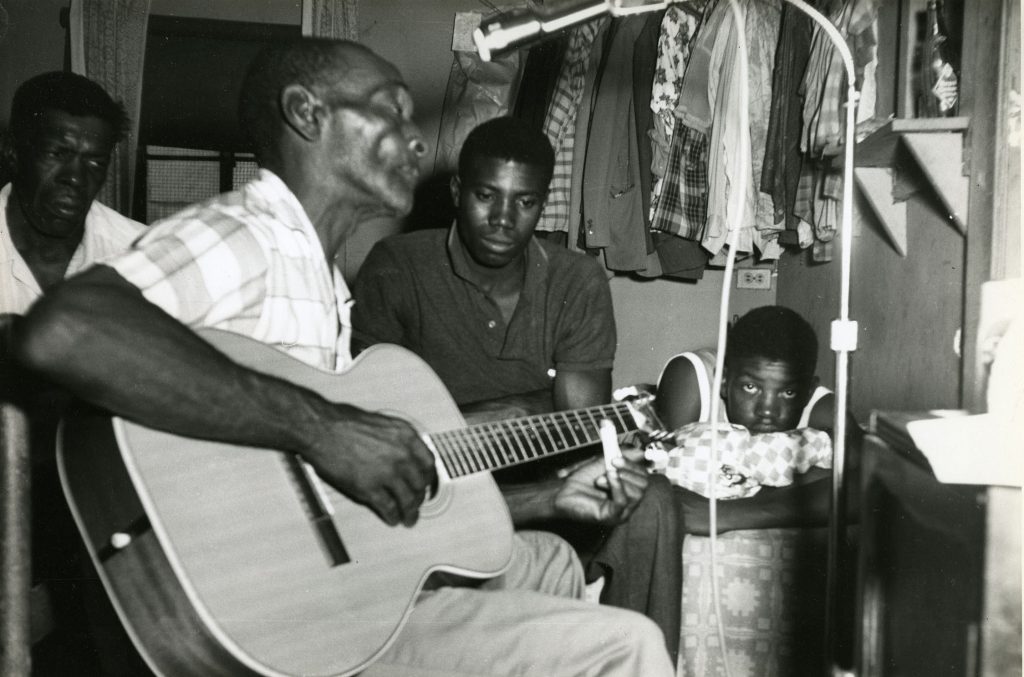

Finally, there’s the music. On Aug. 4, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings releases Playing For the Man At Door, a 66-song box set of field recordings made by McCormick between the 1950s and ’70s, along with 128-page liner notes that include essays from producers Jeff Place and John W. Troutman on McCormick’s life, the musician’s daughter Susannah Nix on growing up with the massive collection, and musicians and scholars Mark Puryear and Dom Flemons on the marginalized communities to which McCormick devoted his life’s work.

Finally, there’s the music. On Aug. 4, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings releases Playing For the Man At Door, a 66-song box set of field recordings made by McCormick between the 1950s and ’70s, along with 128-page liner notes that include essays from producers Jeff Place and John W. Troutman on McCormick’s life, the musician’s daughter Susannah Nix on growing up with the massive collection, and musicians and scholars Mark Puryear and Dom Flemons on the marginalized communities to which McCormick devoted his life’s work.

Any controversy about McCormick vanishes when listening to these songs. The field recordings are McCormick at his obsessive best—on the street, being so bold as to request someone perform for his recorder (a request usually fulfilled), taking notes, occasionally interjecting a question, trying to capture the moment, in living rooms, porches, backyards, bars, and even prisons.

There are some familiar names. The storytelling preceding songs like Mance Lipscomb’s version of “Tall Angel at the Bar,” and Lightnin’ Hopkins’ duet with Long Gone Miles, “Natural Born Lover,” is priceless. But most of the performers of these recordings were neither famous nor notorious outside their communities. I got to know some of the lesser-known characters, including barrelhouse pianist Robert Shaw, the ethereal Gray Ghost, and drummer-rapper Bongo Joe Coleman (what may be his first recordings). Performing live in person, each comes off as an original.

Revelations abound. “Quills” by Joe Patterson features one of the last players in Texas skilled in blowing handmade quills, or pan pipes made of cane, a talent famously articulated by Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas from Big Sandy in the 1920s, who McCormick also extensively studied. “St. James Infirmary” by Dudley Alexander and Washboard Band, sung in English and French, is a stellar example of Creole music that predates zydeco.

Mack McCormick leaves behind a dilemma. He was a terribly flawed individual. He obsessively guarded what he knew. He became paranoid his research would be stolen. In other words, McCormick consigned himself to death before the rest of the world could learn what he knew.

The world that McCormick dove into so zealously is gone.

What is left is all that McCormick learned about Texas blues and roots musicians, particularly African Americans. That work was both critical and monumental. Now that that knowledge is accessible, recognition of what he did is something to celebrate, nevermind the baggage of the tortured life that came with it.