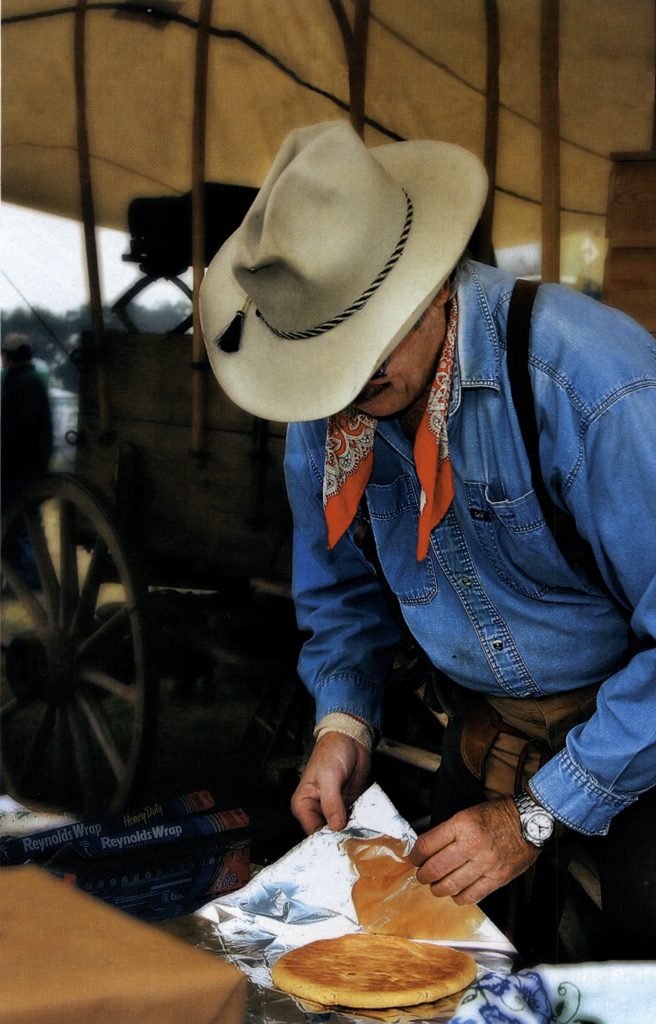

Recipe for success. A participant at the Linn-San Manuel Country Cook Off wraps pan de campo in aluminum foil. Photo by Rebecca Rivera.

An hour after sunrise, Mesquite smoke hanfs like a low fog over the cooking teams preparing their entries in the 26th Annual Linn-San Manuel Country Cook-Off. The mingled aromas of roasting meats, bubbling beans, and hot pan de campo, or cowboy bread, can bring a strong woman to her knees, plate in hand.

On the first Saturday in December, more than 20 teams, with names like Los Beefy Boys, La Esperanza Ranch, and the Blazing Bandits, each with four official cooks and a platoon of helpers, set up their outdoor kitchens and fire pits behind St. Anne’s Catholic Church on US 281, about 20 miles north of Edinburg. Categories include fajitas, pork ribs, charro beans, roast goat, beef ribs, carne guisada (beef stew), chili con carne, and open class. But the mainstay—the catalyst for the cook-off—is pan de campo: inch-thick bread leavened with baking powder and baked in a Dutch oven. Mesquite coals—below and heaped on the lid—provide the heat.

“In 1924, when he was 12, our grandfather was a cook’s helper on a ranch,” says Rick Hinojosa as he works with several family members at the Outlaws and Lawmen kitchen. He pushes a thin, 18-inch-long rolling pin over the dough, a skill he learned from his grandfather. “He taught us about the heritage of the ranches, Santa Anita and San Juanita. Whenever there was a cattle drive, cowboys would be out there for two to three months working all the ranches in Zapata, Starr, and Hidalgo counties.”

Hinojosa slides the round pan de campo onto a slotted tray and flips it in the air like a pancake. A traditionalist, he acknowledges that judges have their own preferences in texture and taste. “But if you can’t open it up to put butter and honey inside or use it to sop up gravy, it’s not pan de campo,” he insists.

Most teams, like Hinojosa’s, are family. His sister, Chris Hernandez, adds warm milk to a mixture of fl.our, baking powder, shortening, and salt, showing her 15-year-old nephew Josiah how to sweep the dough around the wide bowl and knead it briefly. Hinojosa’s brother Reuben, who oversees the pits where the meats cook, checks the simmering pots of beef stew. The three siblings’ parents helped launch the initial pan de campo contest around 1982.

Melissa Guerra, author of Dishes of the Wild Horse Desert, a border-cuisine cookbook that presents a wealth of cultural history, says recipes for breads and salsa were rarely shared in the 1800s. ”All the ranchers were very isolated,” she adds. “They would make up recipes as they saw fit.”

Nibbling a buttered wedge of fragrant pan de campo, I visit other teams as they do baking test runs, gauging the wind and the fire’s heat. I spot a stone molcajete for grinding spices sitting on a trendy granite countertop. Between the al fresco kitchens, a slender teenage girl twirls a pink lariat, takingturns with some boys, who are throwing their ropes over the head and heels of a roping dummy in the shape of a cow.

At Los Compadres’ fire pit, Carlos Guajardo tastes charro beans with a long-handled spoon. Then he holds out a basting brush covered with a deep red sauce flecked with spices, destined for beef ribs. “Run your finger over this,” he says. I take a taste. The burst of flavor, spicy, but with depth, has a hint of sweetness. “That’s the maple syrup and brown sugar,”he explains.

Lynda Campos, another Los Compadres cook, spoons up a cup of chili, saying she’s been tasting too many things this morning. Offering me the chili and a spoon, she asks, ”What do you think?”

“Great flavor,” I say, “although I would use a little more salt.”

Gathered around an open grill, another group of cooks calls to mind doctors hovering over a challenging patient. Each offers an opinion before concurring: Let the brisket cook a few minutes more. The smoker lid closes.

After my sips and samples (teams cannot sell their products), I head to the booths that are selling pan de cam po, tamales de Veracruz (tamales wrapped in banana leaves), pork tacos topped with guacamole, stew, fajitas, locally made chorizo (a spicy sausage), and pastries. Eating at a long table under a pole barn, I watch the auction ofitems ranging from afghans and pecan pies to a guided buck hunt. Inside the church hall, an animated crowd is playing chalupa (a form of bingo) and buying entries from the baking contest.

Around the midday deadlines, I spot cooking teams turning in their entries. Raquel Flores, who supervises the judging, lets me slip into the cook-off judging rooms, which smell like my idea of heaven. Four judges twist off sections of pan de campo, noting the taste, aroma, and appearance that will determine the winning entries. Some breads are as thin as saltines; others are flaky. “Personally, I like it flaky on the outside with a hint of sour from buttermilk, like my grandma’s bread,” says one judge.

The four judges sampling 21 pork-rib variations appear to be enjoying themselves, too. “The hard part is not eating the whole rib,” says judge Nick Bazan. Soon the winners are announced: The Los Compadres team captures first place for its pan de campo, taking away a trophy and bragging rights. And I only sampled their beans and sauces! Smelling of mesquite smoke, bolstered by huge helpings of coconut-raisin bread pudding, I head home wishing for reincarnation as a Linn-San Manuel Country Cook-Off judge.