Entertainer Nat King Cole performs at the Longhorn Ballroom in 1954. The show was booked by Jack Ruby, the nightclub owner who killed Lee Harvey Oswald. Photo courtesy the Briscoe Center, by R.C. Hickman.

Asleep at the Wheel was getting ready to play the Longhorn Ballroom in Dallas on May 13, 1975, when a reporter knocked on the bus door to tell them that their hero, Bob Wills, had just passed away. The news hit the Austin-based Western swing band hard, but cancellation was not an option at the venue: It was built in 1950 as the Bob Wills Ranch House.

“There was no better way to honor the life and legacy of Bob Wills than to play his music at the Longhorn Ballroom,” bandleader Ray Benson said. “It was a night I’ll never forget.”

The memories—and the music of Wills and the Texas Playboys—will come flooding back on March 30, when a gussied-up Longhorn Ballroom reopens after four years of dormancy with Benson and the Wheel performing, followed by Old Crow Medicine Show the next night.

The 2,000-capacity dance hall’s barn-shaped marquee once famously touted the Sex Pistols and Merle Haggard’s successive shows in January 1978. Thirty-nine members of the Country Music Hall of Fame have performed there, as well as such R&B greats as Ray Charles and Al Green. The size of a football field, with the singer on the 50-yard-line, the Longhorn was known for its acoustics and sightlines, and an ability to host various styles of popular music. Even Motorhead and Red Hot Chili Peppers have graced its stage.

The venue’s name was changed to the Longhorn Ballroom in 1967 when the club’s longtime manager Dewey Groom, the late leader of the swing band the Texas Longhorns, bought the four-acre complex, which includes a motel and restaurant, for $350,000. He commissioned a gigantic fiberglass steer, with an 18-foot horn span, to stand at the entrance, but a more financially fitting mascot would have been a white elephant. Groom struggled to stay afloat until finally selling in 1986; other owners, including Jack Ruby, lost money fast. The Lee Harvey Oswald killer couldn’t make a go of the Longhorn in ’54, and had to give it back to O.L. Nelms, an eccentric real estate tycoon who once took out billboards thanking Dallasites “for making me another million dollars.”

Nelms built the club to entice Wills, his favorite musician, to move back to Texas from California. With “Faded Love” on the charts, 1950 was Wills’ last good year before I.R.S. troubles cut short his Longhorn reign, though he’d return to the bandstand, often making his dancefloor entrance on Punkin, his horse with rubber-soled shoes.

Four Longhorn owners after Groom attempted to revive the Ballroom to its past glory, but only succeeded in keeping it from being torn down. The last person to try, Jay LaFrance in 2017, declared bankruptcy within two years.

But here comes investment professional turned music impresario Edwin Cabaniss, the latest steward of this Texas music shrine. “I’m aware of the [venue’s] history of financial ruin, but we’ve got a 13-year track record with Kessler Presents,” Cabaniss says of his concert business, which has turned two discarded movie houses, The Kessler theater in Oak Cliff in 2010 and The Heights Theater in Houston in 2016, into 500-capacity listening rooms that rock. “And we’ve got some very strong stakeholders to see this project through.”

Cabaniss’ investors, who helped rebuild the Kessler and Heights, are all on board for this bigger venture. Plus, the new Longhorn has a bank partner in Frost Bank, which has lent Cabaniss the rest of the money needed to restore the Longhorn. He declined to name the loan amount, but estimates the entire project, which includes a motel and restaurant, will cost $15-20 million.

The city of Dallas is also helping, having recently approved a $2 million grant plus $2 million in reimbursements for work Cabaniss’ crew does in improving the infrastructure of that desolate corner of Corinth Street and Riverfront (formerly Industrial) Boulevard, ruled by a traffic light that’s 35 years old. The Longhorn is just a mile from Gilley’s Dallas location and is considered part of the Cedars/Southside entertainment district, though its immediate neighbors are a salvage yard and a tire repair shop.

The Kessler Presents team, whose artistic director, Jeff Liles, booked punk and metal acts at the Longhorn in 1986, is approaching the revitalization task in three phases, starting with the live music room, which has the flexibility to host more intimate seated shows, like “An Evening with Emmylou Harris” on April 22 and 23, as well as general admission rock concerts like Dinosaur Jr. on April 28.

Using the football stadium skybox model, the Longhorn has nine suites, four bought by sponsors, and five available to rent on a show-by-show basis. (Don’t diss the rich: Revenue raised by the VIP experience keeps the ticket price down for everybody else, Cabaniss says.)

The project’s second phase will rehab the old motel and restaurant, with phase three building a large outdoor concert venue, framed by the levees of the Trinity River, behind the Longhorn.

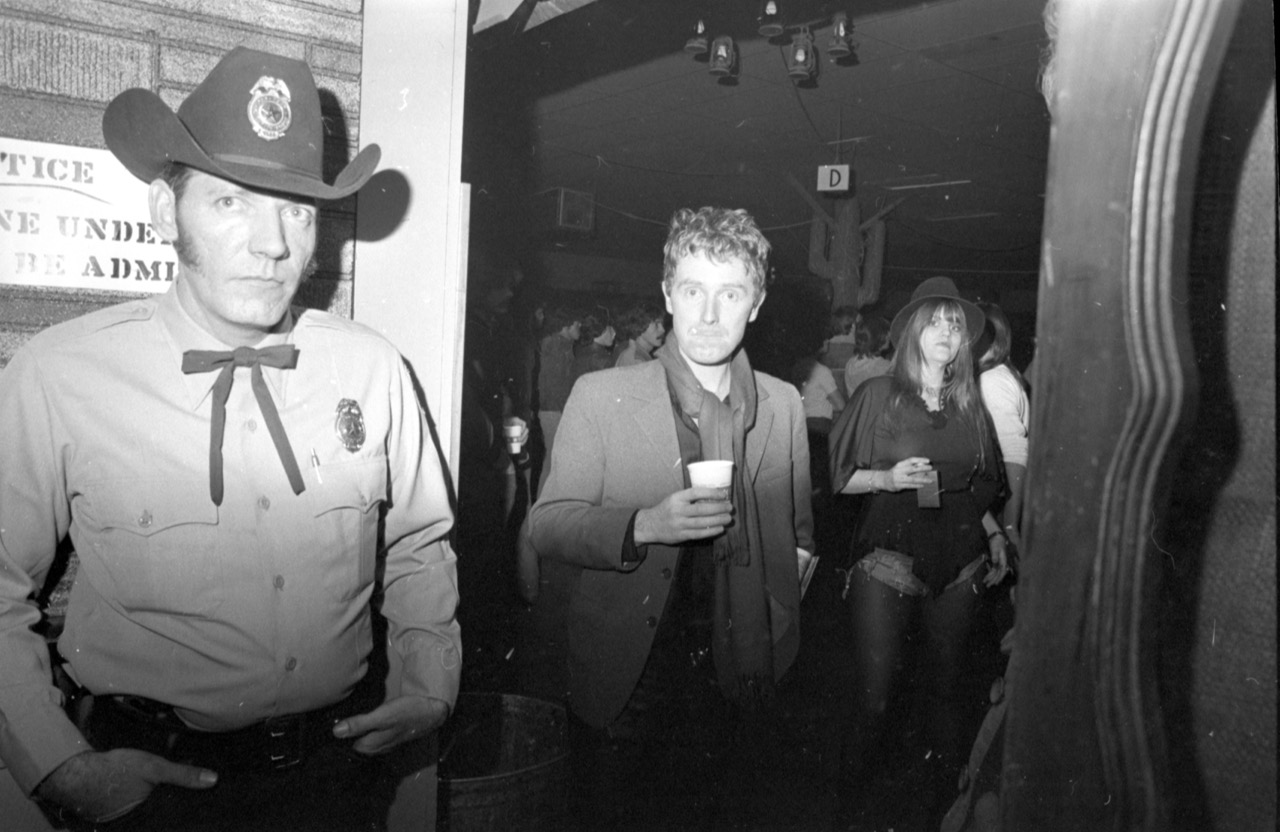

Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren (center) at the Longhorn Jan. 10, 1978. Photo by Kirby Warnock, used with permission.

Though the ballroom was known for hosting Nashville legends, Groom corrected anyone who called his club a honky-tonk. Back in its prime, it was “the nation’s most unique ballroom,” a classy joint with reserved tables and washroom attendants. Music transformed the spacious room, as the talents of Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, and Count Basie obscured the Old West ornamentation, from the wagon-wheel chandeliers to the support beams painted to look like cacti to the silver dollars embedded in the 45-foot bar.

During the first two years of the pandemic, the inactive Longhorn was constantly broken into, with thieves taking not only the copper wiring but artifacts from the walls. Cabaniss and wife, Lisa, who oversaw the ballroom’s interior design, wouldn’t have used the old decorations anyway. A pre-opening tour of the building shows an emphasis on history, not kitsch. What matters is what happened on the stage, which also hosted Otis Redding, Millie Jackson, Johnny Taylor, Johnny “Guitar” Watson, and other soul greats on Sundays and Mondays—the weekend for African American service industry workers.

The legendary venue’s story is told by taking a stroll in the back of the club, where 10 antique shadow boxes display photos, stage costumes, guitars, and other memorabilia from some of the acts associated with the Longhorn. Notable figures range from Wills and Ernest Tubb through Patti Smith, the Ramones, and the Sex Pistols, who played only seven venues on their only U.S. tour before imploding.

“It’s like going to a museum with a beer in your hand,” laughs Cabaniss on the club’s walk of fame, curated by Warwick Stone, who handled music memorabilia for the Hard Rock Café for over 30 years.

The final shadow box salutes the years the Longhorn was run by Raul Ramirez, who owned a Mexican restaurant on the property and booked top Tejano acts, including Selena and La Mafia, before buying the ballroom in decline in 2001. For the next 15 years he hosted sporadic private events, including weddings and quinceañeras.

Cabaniss had an eye on the property since 2015, but he took his time acquiring it. “I try and use both sides of my brain,” he says. “My right brain is heart, emotion. That’s where I get excited about the possibility. My left brain is the analytical side, and usually has the last word. I did a whole lotta research to see if [buying the Longhorn] was feasible.”

Key to the Longhorn’s allure is its size, giving Kessler Presents a room to which their theater acts can graduate. For instance, an April 1 show with Morgan Wade, a country belter from West Virginia, sold out quickly at the Kessler so it was moved to the Longhorn, where it’s also close to selling out—at four times the capacity.

“We don’t have to say goodbye anymore to the acts that have outgrown the Kessler,” Cabaniss says. “We say ,‘See ya next time.’”

For a rising star like Wade, next time could be at the 6,400-capacity Backyard Amphitheater. Completion is expected by the end of 2024, just in time for the venue’s 75th anniversary in 2025.

Not many music halls from the ’50s get a second chance, or a third, or a seventh, but the Longhorn Ballroom has always been a special part of Dallas history, even when it was closed. You’d drive down Industrial, past all the liquor stores and pawn shops and massage parlors, and see that famous marquee, and if that didn’t do something to your right brain, well, then you’re probably not a music fan.

“When you’re doing a big, drawn-out job like this restoration, you need little cool things to happen to keep you going,” says Cabaniss, recalling a rainy night about a year ago when he saw a man leave a note in a plastic bag on the locked gate. “I have your original sign,” it said.

Cabaniss put the number in a pile, thinking it referred to one of the inconsequential signs scattered throughout Dewey Groom’s Longhorn. But when his project manager followed up, she said the man had the large “Longhorn Ballroom” neon sign that was right over the entrance. Cabaniss thought that sign was gone forever. But things sometimes come back when it’s their time.