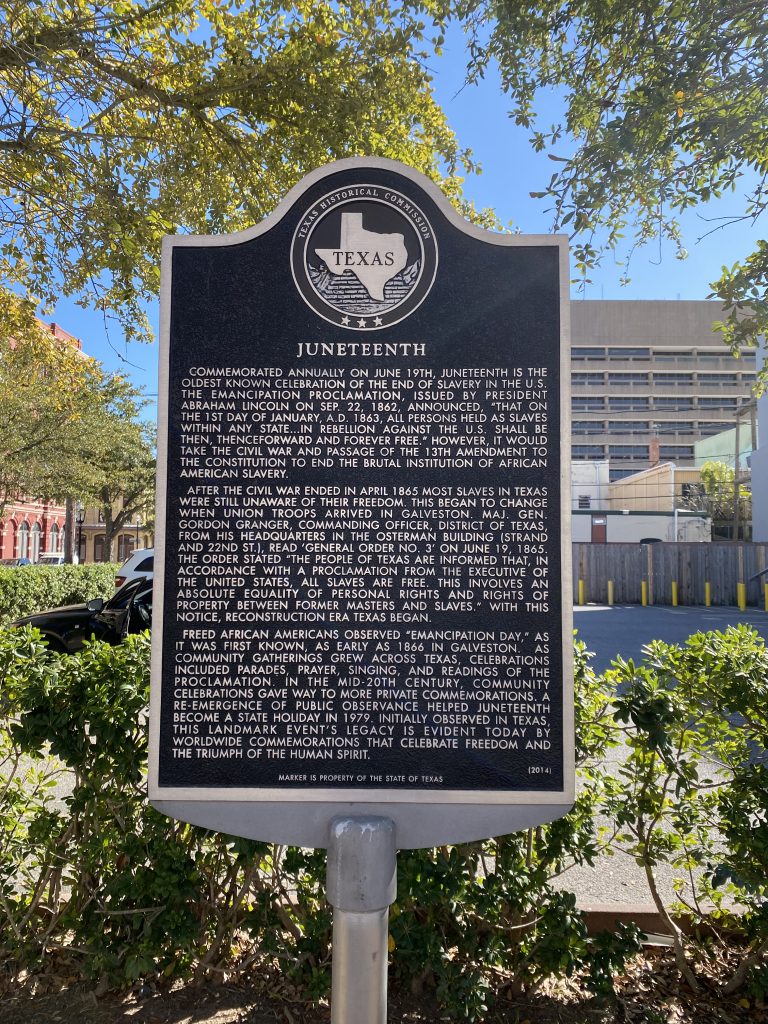

Juneteenth historical marker in Galveston. Photo courtesy Galveston Island CVB.

If you’ve ever thought to yourself, “You know, there really should be a historical marker for [insert a beloved or infamous Texas person, place, or thing here],” now is the time to make it happen.

The 2021 deadline to apply for a Texas state historical marker is May 15. Given that the time between application and installation of each marker can easily take more than a year, it’s never too late or too early for you to begin your crusade to set up a sanctioned memorial for your favorite historic figure, community, event, or building in the state.

Designating historic sites in Texas dates back to the 1850s, with the marking of graves at the Battle of San Jacinto. In the 1910s, the Texas Legislature secured funding to preserve more of the people, places, and events that tell the story of Texas, including the gravesites of Sam Houston in Huntsville and Elizabeth Crockett (Davy’s wife) in Acton, and the famous King’s Highway, aka Camino Real. Things really took off in 1936, when 1,100 markers were placed around the state to commemorate the centennial of the Texas Revolution.

Today, the Texas Historical Commission’s program has more than 16,000 markers. They range from one memorializing the founding of Texas Zydeco music in the Frenchtown section of Houston’s Fifth Ward (marker is located at Collingsworth Street and State Highway 59) to the site of the Leanderthal Lady, a more than 10,000-year-old skeleton of an original Austin suburbanite (Ranch to Market Road 1431, approximately 1 mile west of Parmer Lane).

If anyone knows a thing or two about the application process it’s Houston historian and author Mike Vance, who has served on the Harris County Historical Commission for 12 years. “I’ve worked on dozens of markers, from doing them all by myself to being on proofreading and advisory groups on the history part,” he says. (Full disclosure: I also once co-wrote a book with Vance.)

First, he says, the decision begins at the county level with final approval coming from the state. By statute, each Texas county—from teeming Harris (population: 4.7 million) to sparse Loving (population: 169)—has its own county historical commission.

“Somebody would go to the county historical commission, or somebody already on the commission would say we need a marker for this or that,” Vance says, describing the way the process usually is initiated. “There would in theory be someone from the commission who would mentor the applicant if an outsider brings something in.” By “outsider,” he means anyone not on a county commission.

Once completed, the idea is put to the state commission in Austin for final approval. The more prepared your pitch is, Vance says, the better it will fare. “We get narratives brought to us that are woefully inadequate, and in theory we pass those on to the state with all the rest,” he says.

In reality, only the best applications, the ones that wow county officials and arrive in Austin with glowing recommendations, have a chance of success. Vance therefore advises dotting your i’s and crossing your t’s before you send in your bid. Even though this is history and not math, you have to “show your work.”

“The research and writing do indeed matter a great deal,” he says. “Everything has to be sourced and footnoted. You are convincing a staff of professional historians at the Texas Historical Commission marker program in Austin.”

The full details are here, but at a minimum, you need to send in a five-to-10 page narrative explaining the historical significance of your nominee and proof of ownership of the property (or permission of the property owner) of the site where the marker is to be installed. In the case of landmark buildings, the county will want to see more, including historic photos of the building and current ones depicting each side of the structure, along with floor and site plans, which can be hand-drawn. There is a $100 application fee, applicable even for resubmissions. For help, the commission offers webinars with more tips.

Vance points out that the commission’s choice of markers has changed with the times. For one thing, they have become swamped with applications from church and house of worship congregations. Each flock of a certain vintage feels like they’ve earned a historical marker, Vance says, and while there is nothing wrong with that, and while there certainly is precedent for these markers, the sheer number of them is overwhelming.

Vance points out that some counties have their own historical marker programs and he hopes that these can pick up some of the slack for applications. He admits that while having, say, a Travis or Harris or Nacogdoches county historical marker is not quite as prestigious as one officially bearing the Lone Star of the State of Texas, the upside is a greater likelihood of approval and a quicker turnaround time.

“And the Harris County ones are blue, and very pretty,” Vance says. “In El Paso County, they have pictures on them, which is also very neat.”

In keeping with the changing times, there is now a separate process to catch up with topics either overlooked, or, in some cases, swept under the rug. In 2006, the state launched the Undertold Marker program and began prioritizing markers that address “historical gaps, promote diversity of topics, and proactively document significant underrepresented subjects or untold stories.”

“Especially in these counties of less than a billion people, the commission was always good ol’ boys—or actually lots of women, because women were always involved—but the point is, [they were] very white,” Vance says. “And I think it was not out of actual malice, but that they just didn’t look at Black history, or Tejano history, as a theme. They didn’t know their stories and they didn’t seek them out.”

In addition to Black and Tejano history, the Undertold Markers program has immortalized the stories of smaller ethnic communities like the Chinese-Americans of Houston, the Koreans in Texas (with a marker in Dallas), the Poles of Bexar County, the Japanese of Webster, in rural mainland Galveston County, and the Syrian-Lebanese of El Paso.

In addition to stories to be celebrated, some of these markers tell of horrors long suppressed including the lynching in Waco of Jesse Washington in 1916, the Porvenir Massacre of 1918, and the Millican Massacre of 1868.

Another Galveston County marker—one in the city of Galveston—tells the story of Jack Johnson, the world’s first Black heavyweight boxing champ. Vance says that markers like that represent two areas the commission is newly interested in memorializing: African American history and sports history.

In addition to ethnicity and sports, the Undertold Markers program explicitly encourages applications covering a grab bag of subjects: music and performing arts, journalists, botany, crime, medicine, the Vietnam and Korean wars, disabilities, writers and poets, cinema, and a host of other topics. The whole list is here.

The Undertold Program has a different process and deadlines (applications for this year will be accepted Oct. 1-Nov. 15). The $100 application fee is waived, for one thing, and the applications are routed through Austin instead of passing through each county first.

One last thing to remember: Markers take time and carry significant out-of-pocket expense. Vance estimates a two-year period between application, approval, forging in a San Antonio foundry, shipping to your address, and sticking the sign in the ground, at a total cost of $2,400 or thereabouts. Luckily, it’s usually not hard to find friends and supporters to help defray the costs.

Vance applauds the new direction of the commission, even as he laments some of those they’ve put up in times gone by. ““Today’s Texas state markers are a ton more reliable than they used to be in the old days,” he says. “Some [were] just completely wrong on the history, but nowadays, the THC wants you to get it right.”