Davis Mountains Preserve by night.

Waltz across Texas and you’ll find coastal marshes where alligators lurk, spring-fed pools in the middle of the desert, and green-blue creeks sandwiched between cypress-lined banks.

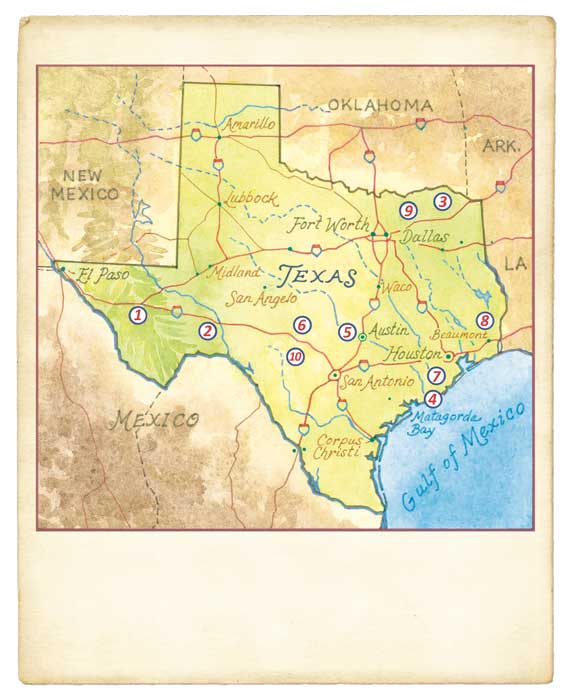

We’re a great big diverse state, but most of us live in bustling cities, drive crowded freeways, and spend our days inside air-conditioned buildings. We need nature but local, state, and federal governments can’t manage and protect all of our sacred places. Luckily, organizations like The Nature Conservancy help fill in the gaps. In Texas, The Nature Conservancy manages 38 preserves, and many of them open periodically for exploration by the public.

Illustration by Elizabeth Traynor

“Because we’re such an urbanized state, these places are important ecologically, spiritually, and culturally,” says Laura Huffman, Texas state director for The Nature Conservancy.

The Nature Conservancy is funded primarily through membership dues and donor contributions. Volunteer work days and citizen science opportunities take place year-round at sites across the state. To receive updates, to donate, or to sign up to become a member, go to nature.org/texas.

One of the largest conservation organizations in the world, The Nature Conservancy first became active in the Lone Star State in the 1950s and established its Texas chapter in 1964. Early on, it spearheaded an effort to save Enchanted Rock—that glowing dome of granite where rock climbers, hikers, and campers flock—from mining development. Since then, it has helped protect nearly a million acres in Texas. “It’s about protecting iconic places so future generations can have access,” Huffman says.

We’ve rounded up 10 of our favorite Nature Conservancy properties that allow occasional public access.

Davis Mountains Preserve

30.70723, -104.09968

A hike to the top of Mount Livermore always reveals some new natural wonder. “Every time I’ve been up, there’s been a different weather pattern—it snows, it sleets, or it’s windy as heck when you’re standing up there, holding on with white knuckles and elated,” says Jane Schweppe, who along with her sister contributed $2 million for the 1992 purchase of the original parcel.

The peak, the highest in the Davis Mountains and fifth highest in Texas, caps a biologically diverse “sky island” that rises above the Chihuahuan

Desert in West Texas like Mother Nature’s penthouse suite.

The Nature Conservancy protects more than 100,000 acres of canyons, cliffs, and mountainsides. It’s not just land that’s protected, either. The preserve tucks away a piece of West Texas’ ranching culture for safekeeping and stops the bright lights of development from detracting from the skies around nearby University of Texas McDonald Observatory.

The preserve’s entrance gate is about 25 miles northwest of Fort Davis.

2018 open days: March 16-18, April 14, May 19, July 13-15, Aug. 10-12, Oct. 13, Dec. 7-9.

Independence Creek Preserve

30.45274, -101.79735

Turns out West Texas isn’t all prickly cactus, deep-cut canyons, and scrub-covered mesas after all. In a remote corner of the state, you’ll find water tumbling through rocky creekbeds, an almost mystical grove of gnarled old oaks, and two spring-fed pools filled with gin-clear water. This distinct and critical preserve covers close to 20,000 acres a stone’s throw from the headwaters of Independence Creek, just above its confluence with the Pecos River.

Swimming across one of the two lakes formed by a small dam or dangling your toes off the edge of a wooden dock, you might think you’ve been mysteriously transported to someplace tropical—until you hear the barking from a nearby village of fat prairie dogs, just out of eyesight.

“Independence Creek Preserve safeguards one of the most important of the few remaining freshwater tributaries of the lower Pecos River and protects more than 19,000 acres of the Chihuahuan Desert, including vital habitat for a number of rare bird and fish species,” Huffman says. “It’s an ecological powerhouse and part of the fabric of West Texas’ natural heritage.”

Independence Creek Preserve is located 22 miles south of Sheffield.

2018 open days: March 24, April 20-22, May 26, June 22-24, July 28, Aug. 24-26.

Lennox Woods Preserve

33.75243, -95.10729

A looping trail on an old wagon road used from the 1840s to the 1930s takes hikers through hardwood forests to a tributary of Pecan Bayou at this preserve in northeast Texas. The old growth forest blazes to life in the fall, when the leaves turn. In spring, wildflowers pop up underfoot.

The highlight? Trees 100-plus years old create woods protected by landowners for four generations. The preserve includes a 350-acre tract accessible to the public and a separate, larger tract where restoration work is taking place.

Shortleaf pines, loblolly pines, hickories, and red maples dot the upland areas; the bottomlands are shady and dense with oaks and sweetgums and a threatened plant called the Arkansas Meadow Rue. An endangered beetle, the American Burrowing Beetle, makes its home here, too.

Lennox Woods Preserve is located along State Highway 37 in Red River County, about 10 miles north of Clarksville.

2018 open days: sunrise to sunset daily.

Clive Runnells Family Mad Island Marsh Preserve

28.66114, -96.08989

Researchers from the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center set up a temporary research station here every spring, netting (and quickly freeing) Neotropical birds as they fly on the Texas leg of their long-distance commutes across the Gulf of Mexico. The data they gather provides clues to bird populations and migratory patterns.

Since the Audubon Society started its Christmas Bird Count in 1993, the annual survey that incorporates the preserve has often ranked No. 1 in the country for bird diversity. Among the stars is the hooded warbler, a yellow-and-black masterpiece of a bird that winters in Central America.

A rare remaining chunk of a fragile system of prairies and wetlands that 100 years ago stretched nearly unbroken along the Texas coast, the 7,063-acre preserve features marshes that protect water quality and provide habitat for white-tailed deer, alligators (lots of them!), bobcats, rattlesnakes, and coyotes.

The preserve is located off FM 1095 in Matagorda County, southeast of Collegeport.

2018 open days: The preserve hosts monthly bird-watching events called Feathered Fridays (reservations required); otherwise on volunteer workdays or by appointment only.

Barton Creek Habitat Preserve

30.27999, -97.90931

This section of Barton Creek bears little resemblance to its high-profile downstream neighbor, Barton Springs Pool in Austin. Here, midway between the headwaters of the roughly 50-mile creek and Lady Bird Lake in Austin, you’re more likely to hear a screech owl hooting from a treetop or spot a great blue heron than several hundred bathers frolicking in the chilly waters.

Plans once called for a subdivision with as many as 7,000 homes here. The preserve is a rare undeveloped swath of land close to an urban core, and scientists say it’s critical to protecting Austin’s water resources. The 4,083-acre tract is managed primarily as a habitat for two endangered songbird species. Besides the creek, visitors can explore several short trails that lead to a smaller tributary tucked in the woods.

The preserve is located along 4 miles of Barton Creek in Austin.

2018 open days: Texas Highways special event April 21; otherwise limited to scheduled volunteer workdays and arranged visits.

Eckert James River Bat Cave Preserve

30.57026, -99.3328

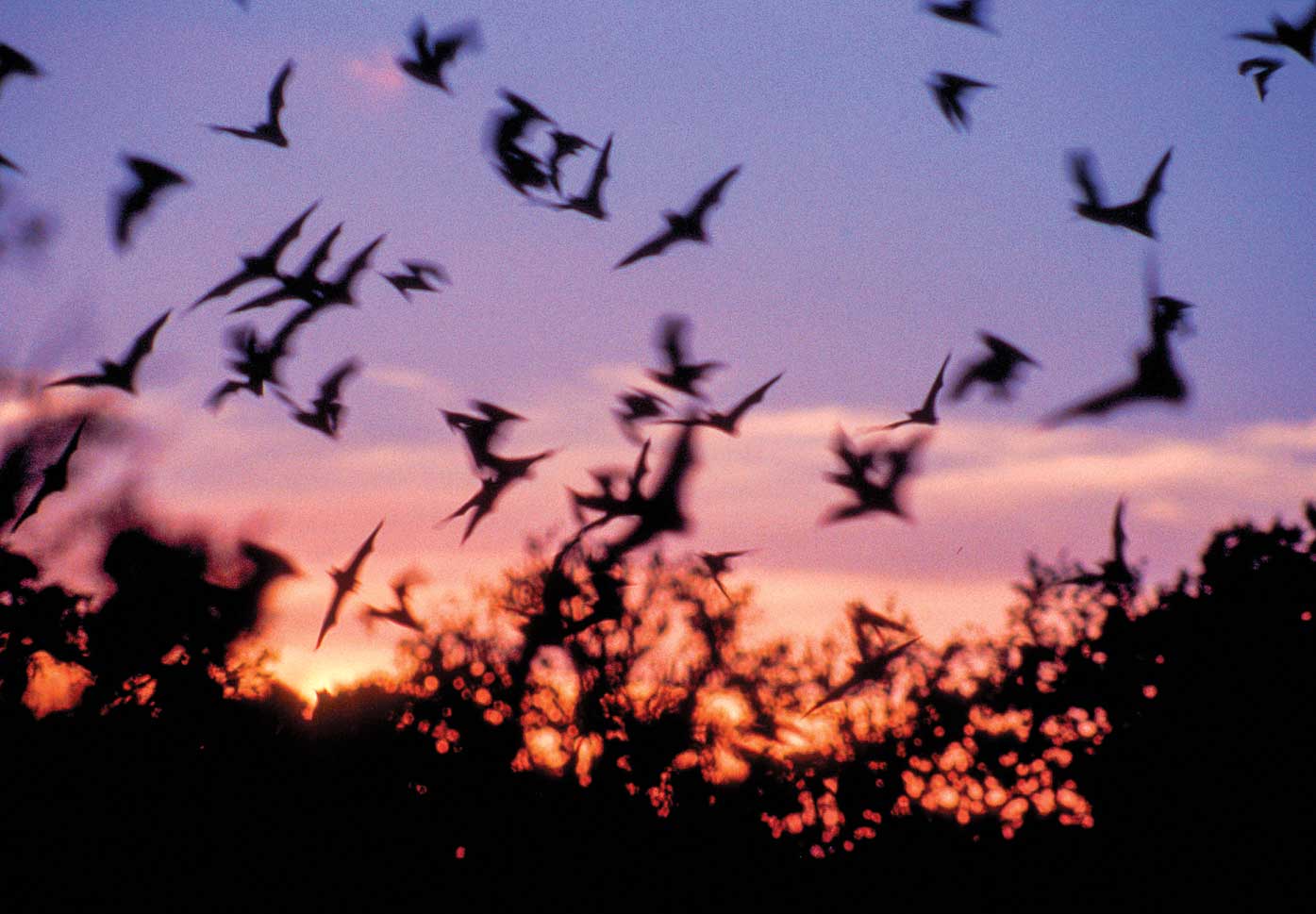

Photo: Lynn McBride

The bat emergence at this slice of Hill Country property southwest of Mason won’t sneak up on you. Just before sunset, a rumpus begins near the mouth of a cave. First, a few tiny mammals streak out. A stream soon follows, like a whirlwind of X-wing Starfighters from a Star Wars flick, tightening into a ribbon that disappears over the horizon.

During the summer, these Mexican free-tailed bats depart nightly from their home in a 65-foot hole in the ground, creating a performance better than anything you’ll see at a movie theater.

“They eat between 400 and 600 bite-sized bugs per hour,” says bat cave steward Vicki Ritter, who provides live commentary as the vortex forms each clear summer evening.

An estimated 1.6 million female bats set up camp here every May to give birth and raise families. More adults move in, and at the population’s peak in late summer, some 4 million bats call Eckert James River Bat Cave home. If you’re lucky, you’ll also spot Otis and Olivia, the resident great horned owls, or one of the white racer snakes, Miss Hiss or Sir Hiss, who hang out in hopes of a quick snack.

The preserve is located 16 miles southwest of Mason.

2018 open days: Thursday through Sunday evenings from mid-May to early October. (A donation of $5 per person age 6 and up is requested.)

Brazos Woods Preserve

29.108389, -95.613829

Photo: Jerod Foster

Herds of bison once stomped through these bottomlands, located along the convergence of two migratory bird flyways. The bison are long gone and so are the cattle that grazed here before The Nature Conservancy acquired this 176-acre parcel in 2016.

These days the focus is on education. Hurricane Harvey delayed construction of a new pavilion, now scheduled to open in late 2018. When it’s finished, visitors will gather there to learn about the bottomland forest’s natural resources as well as water and habitat protection. They’ll hike through wetlands, brushing against native palmettos, gaze up at oaks dripping with Spanish moss, or peer into the muddy reddish water of the Brazos River that borders the property. Lucky visitors might spot a bald eagle, too. Conservationists are working to restore deforested land and bring back native habitat.

The Brazos Woods Preserve entrance is at 1080 County Road 645, West Columbia.

2018 open days: several times a year.

Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary

30.37375, -94.25167

Young longleaf pines sprout like a crowd of foot-tall, long-haired hippies in the forest at the Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary.

Chainsaws and urban sprawl leveled nearly all the mature longleaf pines that once grew in a 90-million- acre swath from Florida to Texas. Today, less than 3 percent of the original forest remains. This preserve was set aside in 1977 to help the species regenerate.

Part of the marvel of this 5,654 acres (including adjoining conservation easements) lies in its diversity. Hike or canoe through the preserve and you’ll find yourself in squishy bogs or swamps one moment, pinelands, sandy uplands, or magnolia forests the next.

Visitors can access an easy 6-mile trail from dawn to dusk daily, or paddle Village Creek, which cuts through the preserve for 8 miles and continues into the Big Thicket National Preserve (check with local vendors for canoe and kayak rentals).

Roy E. Larsen Sandyland Sanctuary is located about 20 miles north of Beaumont in Silsbee.

2018 open days: from sunrise to sunset daily.

Clymer Meadow Preserve

33.30732, -96.24283

Researchers say 99 percent of the Blackland Prairie habitat that once covered 15 million acres has been lost. What remains exists in mostly small chunks. Clymer Meadow Preserve contains one of the largest contiguous remaining pieces.

Even more remarkably, no plow blade has ever cut through the soil on some sections of the property. Its gently rolling land, pockmarked by micro- topography—wetlands just a few meters wide perched atop hillsides—acts as a laboratory for researchers studying everything from monarch butterflies to water quality.

Jim Clymer homesteaded the original parcel in the 1850s. Today, the 1,400-acre preserve is a shifting mosaic of plant life. In late summer, native grasses grow chest high; spring lifts the lid on a treasure box of wildflowers.

Land managers use prescribed fire and periodic cattle grazing to mimic the effects of large nomadic herds of bison that grazed here centuries ago, helping to keep the prairie open.

The preserve is located in Celeste, 60 miles northeast of Dallas.

2018 open days: annual spring and fall wildflower and grassland tours as well as volunteer work days; otherwise by appointment only

Love Creek Preserve

29.79104, -99.4279

Photo: Ian Shive

A hike down to Love Creek could turn up anything from a Medina roundnose minnow—known to occur only within the upper Medina River watershed—to a coveted golden-cheeked warbler, whose buzzy chirp you’ll probably hear before you see the endangered bird.

You might spot a rare Tobusch Fishhook Cactus, too, or you could wander into a cluster of bigtooth maples—called “lost maples” because they’re few and far between in Texas.

Baxter and Carol Adams sold and donated part of their Love Creek Ranch to protect this mashup of hills and canyons on the western edge of the Hill Country. It’s expanded to more than 2,500 acres today and includes a nearly 5-mile stretch of creek, which flows through the property before merging with the Medina River.

The preserve is located on FM 337, west of Medina.

2018 open days: Christmas bird count in December, date TBD (sign up in advance).

Pam LeBlanc grew up in Austin and writes about fitness and adventure travel at the Austin American-Statesman and Austin360.com, where she pens the Fit City column. Kenny Braun is a photographer based in Austin. His new book, As Far As You Can See: Picturing Texas will be published by the University of Texas Press in April. His book Surf Texas was published in 2014.