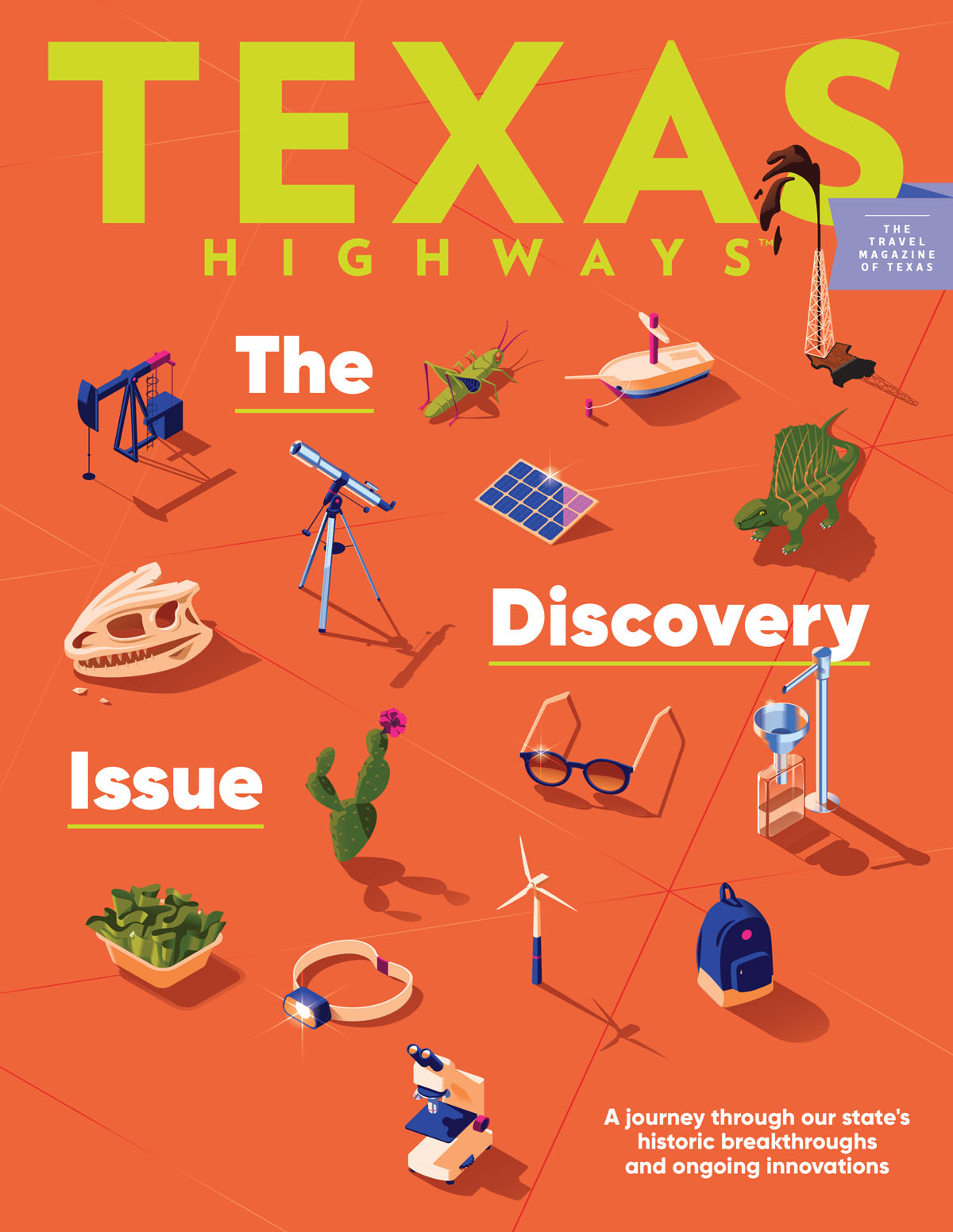

Terry Allen at Arlyn Studios in Austin in May 2019. Photo by Barbara FG

Maybe you’ve seen Terry Allen’s work.

His sculpture Caw Caw Blues, which contains the ashes of his friend Guy Clark, stands sentinel at the entrance of The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos. Countree Music, a 25-foot bronze cast of an oak tree and a map on the terrazzo floor depicting Houston as the center of the world, accompanied by music, is planted in Terminal A near Gate 17 of Bush International Airport in Houston. Passengers entering security gate D30 in Terminal D at DFW International pass under a 30-foot bronze wishbone titled Wish. A life-size statue of CB Stubblefield of Stubb’s BBQ fame stands on the site of his first restaurant on East Broadway in Lubbock. Nestled in the palmetto palm thicket outside The Contemporary Austin-Laguna Gloria on the banks of Lake Austin is Road Angel, a bronze cast of a 1953 Chevy coupe, the car Allen drove as a teenager, accompanied by more than a hundred audio soundbites (including one of mine), that was permanently installed in 2016.

More likely, you’ve heard Allen’s work.

His song “Amarillo Highway,” about a “Panhandlin’ man-handlin’ post-holin’ Dust bowlin’ Daddy” is a much-covered Texas country classic. The churning “New Delhi Freight Train” was first recorded by the rock band Little Feat. At 80, he’s still out there performing with his Panhandle Mystery Band which includes family and friends, among them son Bukka Allen, pedal steel maestro Lloyd Maines, guitarist Charlie Sexton, and fiddler Richard Bowden— often in conjunction with an art opening.

You may have even seen Allen without realizing it. He and his wife Jo Harvey Allen play Oklahoma couple Aunt Annie and Uncle Jim in the Martin Scorsese film Killers of the Flower Moon.

He’s been awarded a Guggenheim fellowship and is in the West Texas Walk of Fame by the Buddy Holly Center in Lubbock. Texas Tech is finalizing plans for the Terry and Jo Harvey Allen Center for Creative Studies.

Call him what you want: the patriarch of Lubbock creatives, the greatest living visual artist from Texas, the other Texas music godfather besides Willie, the storyteller of the American West. It’s all pretty much true.

In 2016, Allen created Road Angel which can be seen at The Contemporary Austin-Laguna Gloria. Photo by Brian Fitzsimmons/courtesy of The Contemporary Austin

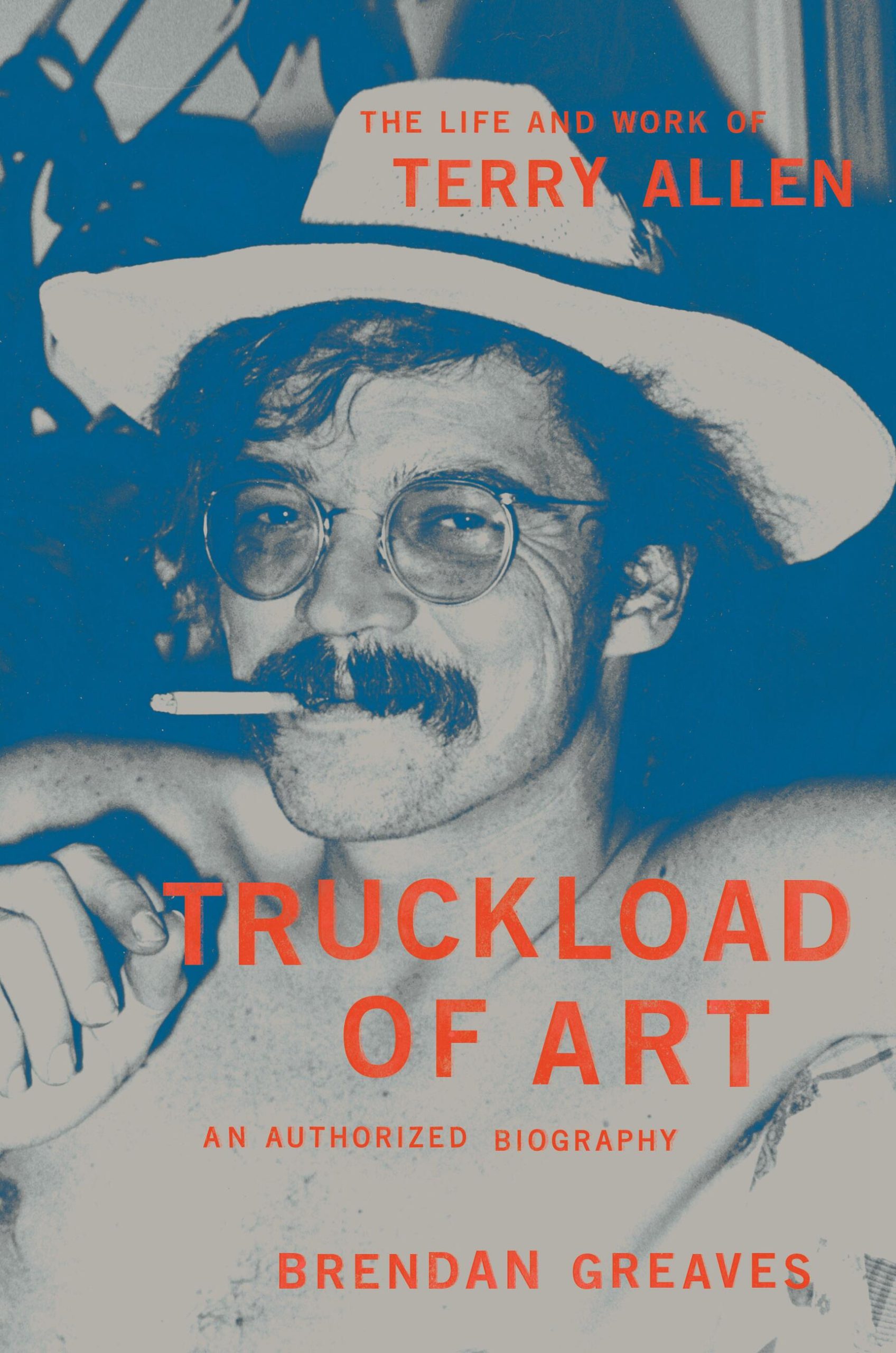

Now comes Truckload of Art, a 500-page biography by Brendan Greaves, to explain it all.

The first Terry Allen art I ever saw made me laugh out loud. The Paradise was a stark diorama of three spaces, the primary space—a parking lot—bathed in red light with the word “Paradise” in pale blue neon script on the back wall as the centerpiece. Directly below is a planter with three measly cacti, two plastic palms, a car tire, and a pair of plastic flamingos. Flanking the planter were doors marked Lounge and Motel in red neon. Beyond the vinyl-covered doors was a motel room with shag carpeting and a honky-tonk bar space with a jukebox. Paradise was part of The Great American Rodeo Show at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in 1976. Eleven artists were given a year to develop a rodeo-inspired piece. Allen paid homage to the kind of spaces where a real rodeo cowboy would feel at home.

The first Terry Allen music I really paid attention to was the 1979 album Lubbock (on everything), marking the artist-musician’s return to his hometown to collaborate with a new iteration of Lubbock music makers, among them singer-songwriter Jimmie Dale Gilmore, who was two classes behind Allen at Monterey High. “I always knew I was destined to write songs,” Gilmore told me recently. “But I thought you had to be really old to be a songwriter. Terry was the first person I saw perform original music. He sang ‘Red Bird’ while playing piano one day at Monterey. That really inspired me.”

Allen and Jo Harvey had been living in Fresno, California, when he came back to make Lubbock (on everything). He instantly became the Don of the Lubbock Mafia of music maker. The Allens eventually moved back—sort of—settling some years later in close-enough Santa Fe.

It’s hard to ignore the tall polymath with stooped shoulders, the piercing eyes of a hawk, and a wide rubbery mouth that can hardly contain his unapologetic flatland twang. Art and music are the same coin, as far as he’s concerned, means to tell stories, which he is very good at doing, in many different ways. He’s so prolific, and so driven to create, he demands to be heard.

Greaves is founder and owner of Paradise of Bachelors Records in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which has reissued Allen’s older recordings and released his most recent albums 2013’s Bottom of the World and Just Like Moby Dick in 2020. Greaves, a self-described “lapsed art worker,” met Allen through the gallery where he worked. He’s collaborated on several projects with Allen and received a Grammy nomination for his liner notes, but taking on the monumental task of telling a very dense story while explaining the dual worlds of art and music, working off journals Allen has kept since junior high, was a whole other deal.

Allen’s father, Sled, a former minor baseball player who promoted wrestling and music events in West Texas, including Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, T-Bone Walker, Jimmy Reed, Ray Charles, Little Richard, and Elvis Presley, who Terry met on one of the six times he played Lubbock in 1955-56, long before most of the world knew who Elvis was. His mother, Pauline, a onetime professional piano player and full-time alcoholic, was 18 years younger than her husband. The biography shows how both inform Allen’s love of performance, his skill at promotion and showmanship, but most of all, his creative drive, providing the inspiration for his DUGOUT series of works.

Allen got his art education at Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts) in Los Angeles. One professor brought visiting Dadaists and surrealists such as Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and Leonora Carrington to lecture. The surrealist Man Ray often stopped by the school to talk to students about the life of an artist. Allen was hooked.

Concurrent with his Chouinard schooling was his pursuit of music. The first song he ever wrote “Red Bird” scored him an appearance on the music television series Shindig! in 1965, generating enthusiasm from Brian Epstein, the manager of the Beatles.

In 1969, he wrote “Truckload of Art,” a song about a real truckload of art from New York destined for Los Angeles to show the upstart West Coast artists how art was supposed to be done, that crashed on the highway. Two years later, a snippet could be heard coming out of the radio of Warren Oates’ GTO in Two-Lane Blacktop, an arty feature film about street racers on a road trip across the southwest.

After graduating from Chouinard in 1966, he began teaching there and followed by teaching gigs at UC-Berkeley and Cal State Fresno.

Truckload of Art focuses on relationships, beginning with Allen’s partner in crime and marriage, the toothsome Jo Harvey. Theirs has been a tempestuous, sometimes competitive coupling while he chased myriad muses and she pursued her career as an actor, playwright, poet, radio producer, and songwriter—whenever they weren’t working together. He thought she should perform only original pieces she created. She enjoyed working in film.

Also documented is Allen’s long friendship with Dave Hickey, the acerbic writer, dealer, curator, and university professor from Fort Worth who opened A Clean, Well-Lighted Place gallery in Austin in 1967, and became the most incisive art critic of his time. Like Allen, Hickey wrote country songs, too.

Allen’s Corporate Head outside the Citicorp Plaza in Los Angeles. Photo by William Nettles

I’m not schooled enough to pass judgement on the art beyond my immediate reaction, and Allen usually makes me laugh. That was the immediate response when I saw Corporate Head, the life-size bronze of a businessman burying his head in the wall of a Los Angeles office building. The publication Atlas Obscura describes the work as “almost whimsical, yet rather grotesque.”

Sometimes the work has an edge too sharp to appreciate. That speaks to Allen’s interest in Antonin Artaud and his Theater of Cruelty, which strived to “shock the audience.” Allen was drawn to Artaud’s 1937 travelogue A Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara about time spent in Mexico among the Tarahumara people experimenting with peyote. His curiosity led to staging his own play about Artaud Ghost Ship Rodez in Lyon, France.

The downs are as interesting as the ups. Juarez, the first of 13 albums he’s recorded, failed to launch as a Broadway musical, despite his collaboration with David Byrne, best-known as the lead singer of the band Talking Heads. The run of the 1994 theatrical play Chippy: The Diary of a West Texas Hooker, co-written with Jo Harvey for the American Music Theater Festival, turned out to be brief, but yielded the song “Fate with a Capital F” cowritten with Joe Ely and Butch Hancock, which remains one of my favorite Allen songs.

Some sweet bits pass by too quickly, such as Byrne’s bewilderment participating in a guitar pull with Allen and friends, and Allen’s dust-up with Tommy Lee Jones over verisimilitude. And I would have enjoyed eavesdropping on Hickey and Allen debating art.

It’s the little things that impress. Allen played in a band in high school with David Box, the teen chosen to replace Buddy Holly in the Crickets after Holly’s death in a plane crash in 1959, only for Box to die years later in a plane crash. In 1972, he played the Dripping Springs Reunion, the precursor of Willie Nelson’s Picnics, thanks to a Dave Hickey booking. Even Andy Warhol and the Manson Family make cameos. He’s been everywhere—Cambodia, France, London, Mexico, and India, telling stories every which way. And he took notes.

With Greaves’ help, Allen tells his most compelling story yet, the story of his creative life.