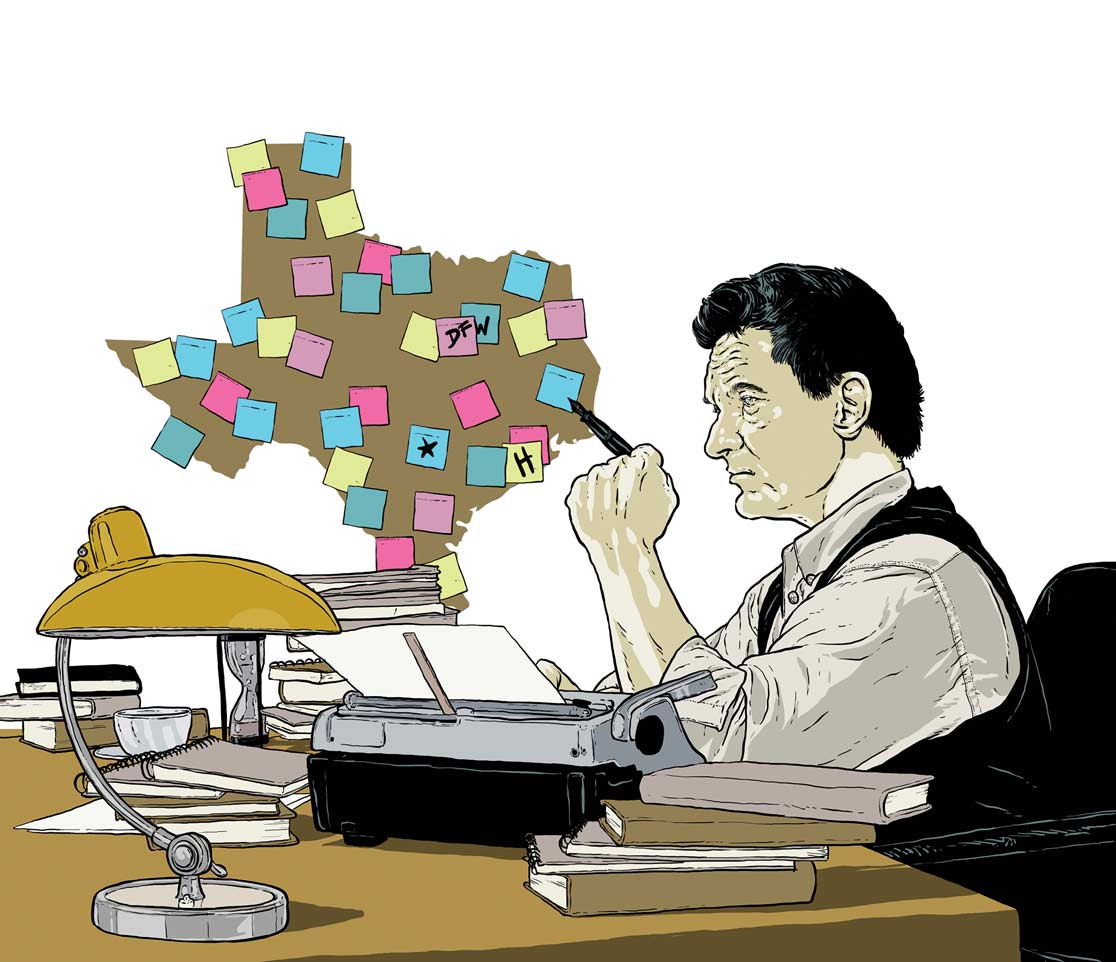

Illustration by Jan Feindt

Lawrence Wright doesn’t do well with downtime.

“I’m horrible, just horrible,” Wright says, lounging in his west Austin home. “I cannot stand not having something to do.” Along with restlessness comes a curiosity and commitment to deep-dive into dangerous and labyrinthine subjects like terrorist organizations, the Church of Scientology, and the Satanic underground. That exacting combination has earned the author and staff writer for The New Yorker a year for the ages.

Lawrence Wright

Will speak about his book God Save Texas and perform with his band, WhoDo, at the Texas Book Festival, Oct. 27-28 in Austin.

texasbookfestival.org

Wright, 71, welcomed 2018 with the Hulu miniseries The Looming Tower, based on his 2007 Pulitzer Prize-winning book about Al-Qaeda and 9/11. Then came the world premiere of his play Cleo, about the love affair between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton during filming of the 1963 epic Cleopatra. Most recently, Wright played a key role in the acclaimed documentary Three Identical Strangers, which is informed by a study he unearthed in his 1997 book, Twins.

That leaves Wright’s new book, God Save Texas, a state survey combining history, memoir, travelogue, journalism, and essays. It is both a boot to the backside of the state’s bravado and a tip of the hat to its spirit, with subtle humor and personal anecdotes gleaned from covering the state for Texas Monthly and, since 1992, The New Yorker. The book grew out of a New Yorker article prompted by the magazine’s editor, David Remnick, who challenged Wright to explain Texas.

“I exercise every day. It’s part of my creative process. When I’m running, I carry note cards and a pen, and just keep the thoughts raw.”

Born in Oklahoma, Wright grew up in Abilene and Dallas and, after venturing off to Cairo, Egypt, and other locales, was lured back to Texas after a magical night in 1979, when he saw Asleep at the Wheel and a young George Strait perform at Gruene Hall. He has lived in Austin, where he moonlights as keyboardist in the band WhoDo, pretty much ever since.

Q: Why did you decide to start God Save Texas with a story about a bike ride with fellow writer Stephen Harrigan?

A: Steve and I ride bikes every Monday morning. Steve proposed that we go down and do the Mission Trail. We were driving down to San Antonio, and he said, “We need to make a stop at Buc-ee’s.” I thought, when I got into the place, “This is where I’m going to begin my book.” And so it was more Buc-ee’s than the Mission Trail. The nice thing about the Mission Trail, it is sort of where Texas history routinely begins. So this is a way of tying the present and the past together.

Q: Traveling around the state to report God Save Texas, what city were you impressed with?

A: Houston. When I was growing up in Dallas, we looked down on Houston, being kind of a roughneck, country music, barbecue spot. But Houston is a city that has taken diversity and made it really work. It’s got a lot of problems—it’s facing a tremendous challenge because of climate change—but the spirit of the city was wonderful. I thought, “This city, it’s really hopping.”

Q: What did you do to pass the time as a kid in Abilene?

A: I was pretty serious about baseball back then. I had an old mattress that I dragged out of our house’s dilapidated garage apartment and put it up against the rear of a neighbor’s garage, and I would pitch at this target on it.

Q: You’re a runner, you’re a biker, you do a lot of hiking—are you a physical fitness junkie?

A: I exercise every day. It’s part of my creative process, running in particular. When I get stopped sometimes, and I just can’t find a door in the room that I’m locked into, I’ll go for a run. And sometimes, within a hundred yards, things will begin to make themselves apparent. When I’m running, I carry note cards and a pen, and just keep the thoughts raw.

Q: Do you think you have a high sense of adventure?

A: I’m on the hunt for stories. If there’s a really good story, I’ll take chances. Like Scientology. I didn’t think they were going to hold a gun on me, but I thought they might sue me or threaten me in some other ways. A couple of times I had people with guns pointed at me. One time I was trying to interview these drug dealers in Tucson, and then in Gaza. But I didn’t feel that they would pull the trigger. I did feel, sometimes, that the person I was with might get killed. I try not to entertain those thoughts because it can be paralyzing if you think, “What’s going to happen?”

Q: Where did you develop your interest in birding?

A: My dad took my wife, Roberta, and me to see the whooping cranes in Port Aransas. This was probably soon after we got back from Cairo in the early ’70s. When we lived out in Quitman I built a purple martin house. When I was piecing it together on the porch, martins came to watch me build the house. It was like they were impatient to take residence. After I erected it, we immediately had a delegation come in and go to each chamber.

Q: How did you first get involved with the Texas Book Festival, where you’ll return this year as a participant?

A: I had started going around the state introducing writers and booksellers. We had this one meeting here in Austin, and the booksellers were sitting around the table with the writers on the side. Bud Shrake was one of the writers. One of those booksellers was remarking about this phenomenal golf book [The Wisdom of Harvey Penick] that people were buying off the dollies when they were bringing the books in. Well, you know, the author of that is Bud Shrake, sitting right across the table from you. They had no idea. Then Steve and I started Texas Writers Month, and this went on for about six or seven years—just trying to get some attention to the fact that there are local Texas writers. And the book festival grew out of that and subsumed it, really, because it was much bigger and more consequential.

Q: Do you consider yourself a Renaissance man?

A: People say that, but I’m just trying to live my own life, and I guess part of what’s going on with me is that I never felt that I had really reached a level in my career where I truly connected with an audience until I got to The New Yorker. I was 45 years old, and everything that has been of real importance to me happened after that. I feel like it wasn’t 20 lost years, but it was 20 years of laboring in the vineyards and with little acknowledgement and few opportunities. So once I got to The New Yorker and began to connect with a larger audience and opportunities opened up, I felt I’ve got to make up for that time. People my age are retiring or dying, and I’m still trying to make it.