Thomas’ 1995 report of the Picnic’s grand return in the Standard-Times got picked up all over the world via wire services. He took ownership of the story, researching Picnic history for a follow-up piece. “There was no real expert on the Picnic, so I decided to become one,” Thomas says. Though Thomas missed the event’s first couple of decades, his obsession will be legitimized with next spring’s PICNIC: The History of Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Tradition published by the author’s alma mater, Texas A&M University Press.

Luckenbach was an apt location for the Picnic’s revival; it was memorialized in the 1977 Nelson and Waylon Jennings hit “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love),” which defined the outlaw country heyday. The ’95 show ensured the picnic would continue for years to come. This year’s show, held at Austin’s Q2 Stadium on July 4, took place half a century after the first.

“Even though it’s certainly had its changes over the past 50 years, with fancier venues and more contemporary artists, there’s a familiarity when you step into whatever venue it’s at that year,” says Ellee Durniak, who, as Nelson’s grandniece, has been attending the Picnic since she was a baby.

The Picnic grew out of the three-day 1972 Dripping Springs Reunion, which aimed to be “the Hillbilly Woodstock.” Organizers projected 60,000 fans a day coming to see a mix of Nashville legends like Loretta Lynn, Buck Owens, and Merle Haggard performing alongside Texas nonconformist songwriters Nelson, Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and the like. The lineup was stunning, but only about 20,000 total showed up to the festival at Hurlbut Ranch. “They lost a fortune,” Nelson said of the Dallas promoters in a 1973 interview. “They spent too much money [on advertising] in New York and Nashville, and not enough in and around Austin,” where Nelson had moved from Nashville a few months after the Reunion.

Despite the Reunion’s shortcomings, Nelson saw his future in the longhairs and good ol’ boys who had coexisted in musical affinity at the event. He kept that same vibe when he brought his first Fourth of July Picnic to Hurlbut Ranch the next year, piggybacking off the infrastructure that was in place from the Reunion.

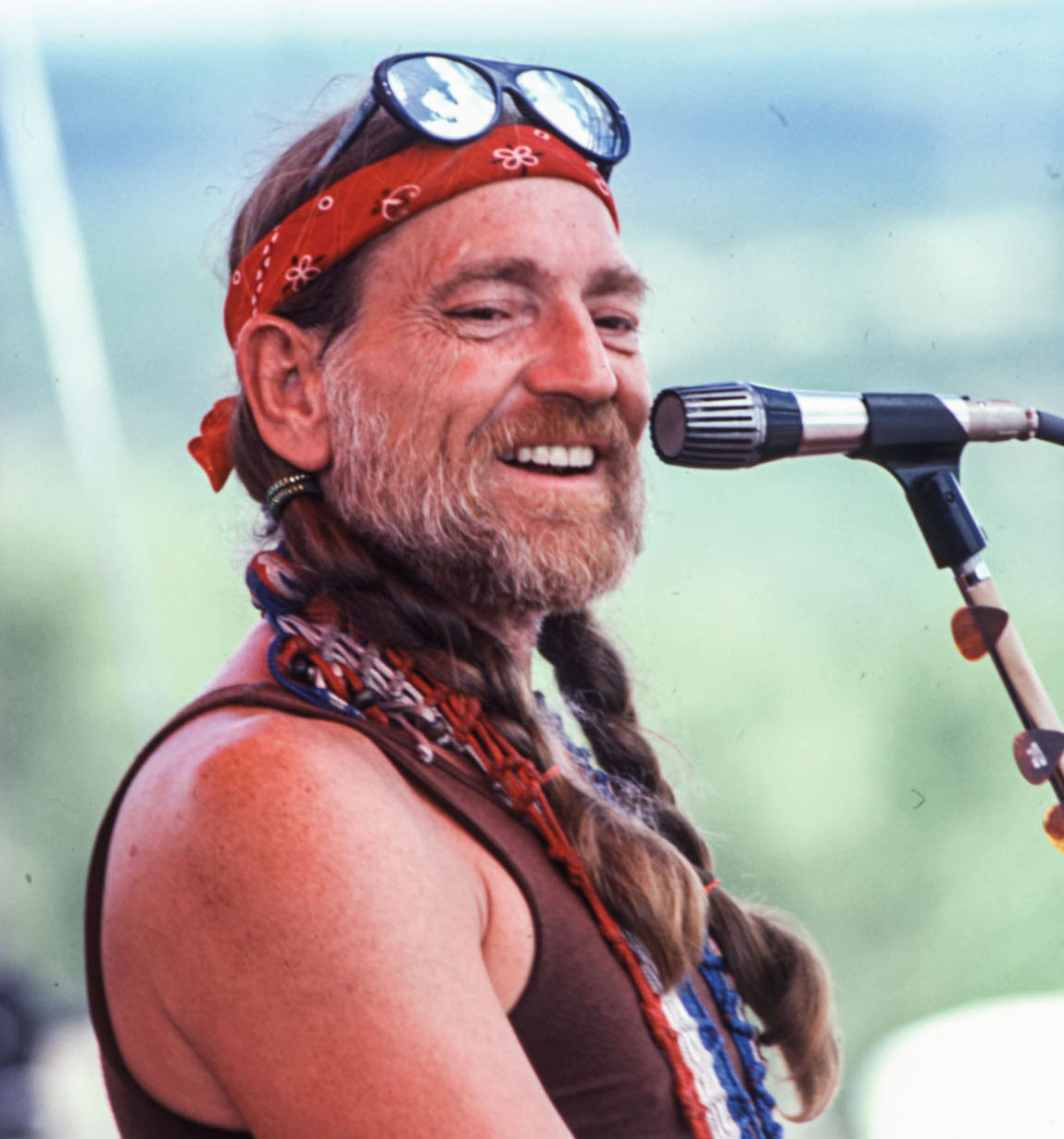

Nelson and the Fourth of July Picnic rose to fame together. When the Red Headed Stranger was planning the first Picnic 50 years ago, he was selling only about 1,000 tickets to his shows. And although his 1973 album Shotgun Willie received critical acclaim, it stalled with the public. So how did Nelson and friends draw about 40,000 fans to the same ranch west of Austin?

Nelson hired the crew from the Armadillo World Headquarters—a now-shuttered music hall and hippie haven that served as Nelson’s hub when he moved to Austin—to run things. The new promoters advertised the all-day festival on rock radio. The biggest draw was Leon Russell, then one of the top touring rock stars in the country. Word-of-mouth confirmed that Russell was showing up to help Nelson celebrate the births of not only the U.S., but also the new country music persona—a figure foreign to the polished way Nashville ran things.

Nelson’s first Picnic was an endurance event as much as a concert. “Traffic backed up ten miles. … Water and restroom facilities were inadequate. … The sound system blew out,” read the press release promoting the second Picnic, held at the Texas World Speedway in College Station. “The temperature reached 100 degrees and there was no shade. Texans love their music, however, and at 2 a.m., July 5, 1973 … happily exhausted fans headed home, unanimously looking forward to Willie’s Second Annual Fourth of July Picnic in 1974.”

Though Thomas was a toddler at the time, he learned to appreciate these first few years through his research. “As fans of Texas music and Willie Nelson, the Picnic is part of our cultural fabric,” Thomas says. “And the early years, from ’73 to ’80, are part of our mythology.”

The Picnics operated with a communal energy. Everybody was just happy to be there, even when they were miserable in the heat and dust. But the sunburned soiree took a dangerous turn in Gonzales in 1976, when 80,000 people showed up, even as the Picnic teetered on the verge of cancellation due to permitting issues. Nelson and Jennings were at their most popular as they topped the charts with the album Wanted: The Outlaws and the single “Good Hearted Woman.” But the bigger audience meant more problems. The Gonzales Picnic featured 44 hours of continuous music—and 147 arrests, mainly for drug possession, DWI, and public intoxication. The Texas Department of Health cited 14 deficiencies, including only 25 port-a-potties for the crowd.

“Willie’s camp now shrugs off the 1976 Gonzales Picnic as simply chaotic, but I think it was actually a fairly dangerous event,” says Thomas, who conducted nearly 120 interviews for the book. “It was very much what the Christian groups that opposed it were fighting against.”

In the 1988 book Willie: An Autobiography, co-authored by Bud Shrake, Nelson writes that as “the Picnic grows beyond control, I try to never worry about what is out of my control—just to give it my strongest positive thoughts and trust for it to turn out well.” When it didn’t, he admitted slipping off to Hawaii to hide out for a week “while the damages were assessed.”

As he dealt with various personal injury lawsuits, Nelson vowed Gonzales would be the last Picnic. But the comeback came just three years later at the Pedernales Country Club Nelson had just purchased about 30 miles west of Austin. Not all his new neighbors approved, so after two years the festival was on the road again.

“It’s not a question of how much money we make, but how much we lose,” Nelson told reporters in 1980. The worst Picnic financially was at Carl’s Corner, near Nelson’s hometown of Abbott, in 1987. Nelson, landowner Carl Cornelius, and promoter Tim O’Connor lost an estimated $600,000.

In the following seven years, there was only one Willie Fourth of July fest, a low-risk affair at Austin’s Zilker Park in 1990. But the five years at Luckenbach, ’95 to ’99, helped right the ship.

Nelson was 40 when he hosted his first Fourth of July Picnic. This year’s 50th anniversary Picnic was a much more organized event, drawing around 20,000 fans. There was even shade. But when 90-year-old Willie Nelson opened with “Whiskey River,” all those crazy years came flooding back.

“You can always count on intolerable heat, great music, incredible people watching,” Durniak says, “and the fact that anything—I mean anything—can happen at the Picnic.”