Mules from U.S. Army Pack Train No. 9 cross the Rio Grande to return to Texas in Lajitas in 1918. Photo courtesy W.D. Smithers Photography Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

In one of his pictures documenting life in far West Texas, photographer Wilfred Dudley (W.D.) Smithers shows a water-delivery boy in Presidio using a can to scoop water from the Rio Grande into a canvas bag draped over a burro’s back. The bag is waterproofed by locally made candelilla wax, and a cow horn serves as its spigot.

In another, a pack train comprising more than 20 mule-drawn wagons navigates the rugged Candelaria Rim southwest of Marfa. Against a backdrop of desert mountains, the teams carefully descend 1,700 feet of switchbacks as they journey to villages and U.S. Cavalry outposts along the river.

“For me, the packer life offered opportunity for countless fascinating observations, some of which I found time to photograph,” Smithers reflected in his 1976 book, Chronicles of the Big Bend: A Photographic Memoir of Life on the Border. “A photographer couldn’t ask for better subjects than the packer and cavalry life, or the natural beauties of the Big Bend.”

But cavalry and wagons represent only a fraction of the subjects Smithers documented in the first half of the 20th century in the Big Bend region of West Texas and Mexico. A self-described “freelance news reporter,” Smithers lived in the area periodically from 1916 until his death in 1981 and spent years exploring the landscape and meeting its people. And at a time when cameras were rare, he captured thousands of images, using an innovative hand-built camera. Designed for portability, it provided a rare perspective on the isolated borderlands.

“I think of Smithers as our resident photographic anthropologist,” says David Keller, an Alpine-based archeologist and historian. “His work on the mule trains put him in a unique position to document that time around the Mexican Revolution. We’d be impoverished without his legacy.”

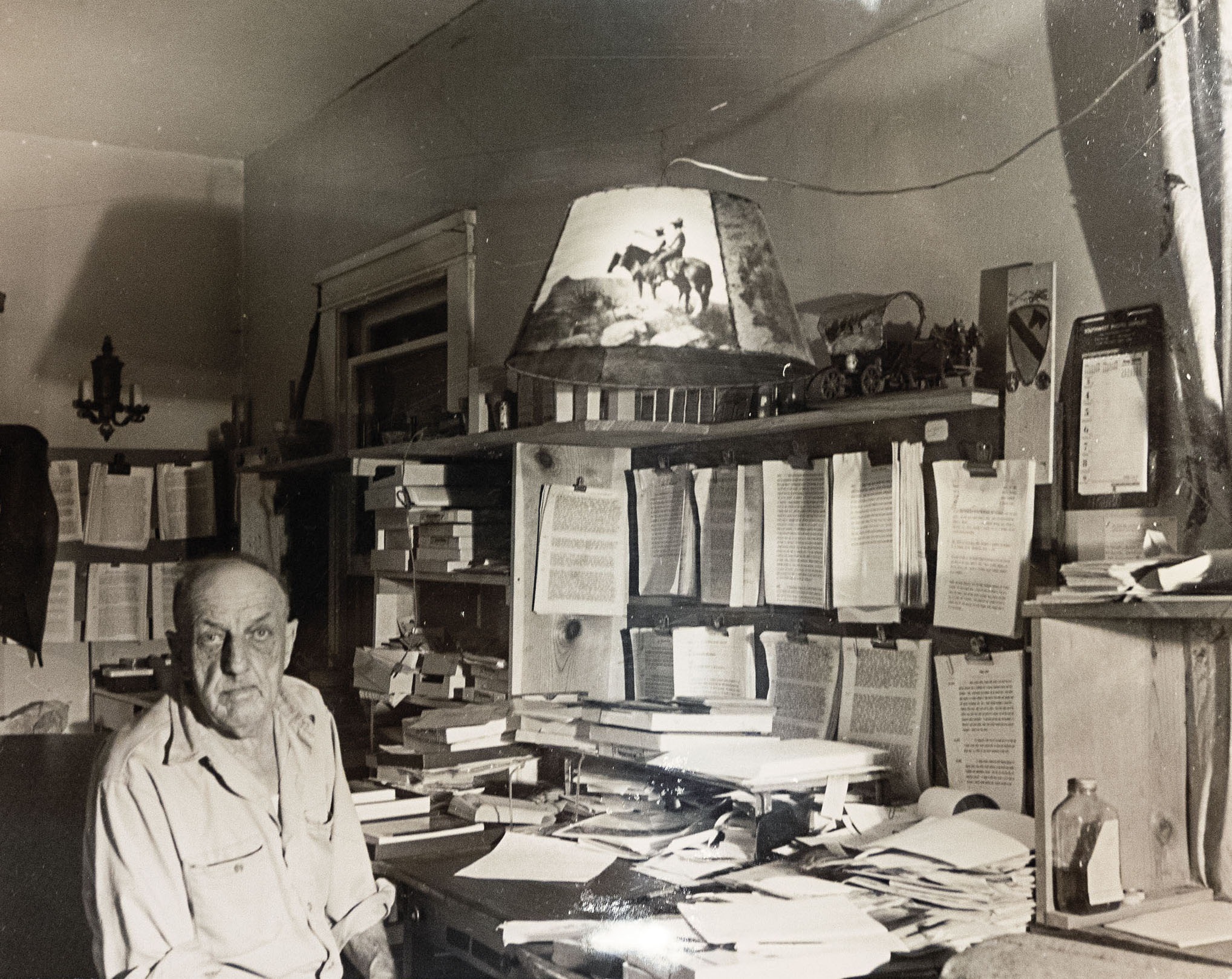

Smithers printed photographs onto lampshades, many of which are now held at UT Austin’s Harry Ransom Center. Photo by Brandon Jakobeit

Smithers processed his images in makeshift darkrooms, drew maps and diagrams of packing systems, and took copious notes about life in the Big Bend. In the late 1960s, Smithers sold his collection for $20,000 to the University of Texas at Austin. Kept at the Harry Ransom Center, the archive contains some 9,000 images with subjects ranging from quicksilver mines to desert wildlife and cacti, Mexican bandits, and the construction of McDonald Observatory. The photos also show the daily living conditions of borderlands people—farming and goat herding families; curanderos, or healers, gathering medicinal plants; and soldiers rodeoing on holidays.

“The most important thing is being there,” says Jim Bones, a renowned Big Bend landscape photographer. “He had a vision of what was happening at the border. It was changing very rapidly, and he was intent on capturing it. It seemed like where anything was happening, he was there. He was so prolific, it’s as though he never slept.”

A Mexican boy fills up a canvas with water from the Rio Grande in Presidio in 1917. Photo courtesy W.D. Smithers Photography Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Smithers, who was fluent in Spanish, credited his childhood in Mexico and San Antonio for his interest in Mexican culture and the Big Bend. He was born in 1895 in San Luis Potosí, where his father was a bookkeeper for the American Smelting and Refining Company. Smithers’ mother died when he was 5, and the family moved to San Antonio when he was 10.

Smithers attended school for only seven years, according to W.D. Smithers, Photographer-Journalist, a master’s thesis written by Mary Katherine Cook in 1975, based partly on interviews with Smithers. As a teen, he worked delivering ice blocks by horse-drawn wagon and in road construction; in the afternoons, he volunteered at San Antonio photography shops.

In his memoir, Smithers recounted the kindness of Mexican families when he was most in need. Curanderos nursed him back to health when he suffered from typhoid as a child in Mexico and later jaundice and heat stroke as an adult in West Texas.

“When he photographed any of the people down along the river, he would come back and give them a copy of the image,” says Mary Bones, director of Alpine’s Museum of the Big Bend and Jim’s wife. “He worked on developing relationships and making people feel comfortable with him, that he wasn’t there just to take stuff from them.”

In the 1960s, Smithers sold his photo collection and extensive notes to the University of Texas. Photo courtesy W.D. Smithers Photography Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Given the price of photography equipment when he was starting out in San Antonio, Smithers built his own camera. He designed it to be lightweight and portable, ideal for fieldwork. He used his camera for decades and built a second version after the first broke. In a caption he wrote for the Ransom Center collection, he said a company called Printex created a camera modeled after his version in 1948.

Smithers became a pioneer of aerial photography in the 1910s. He practiced his craft at the Army airfields in San Antonio, riding in the rear cockpit and sometimes hiring pilots to take him up for commercial jobs. During his enlistment in the Army from 1917-19, he was stationed in California where he helped “train pilots in simulated dogfights with the use of a camera that looked and acted like a machine gun,” Cook wrote. By 1923, back in Texas, Smithers was the “leading aerial photographer in San Antonio.”

Aerial photography was also part of Smithers’ work in the Big Bend, and his experience helped him land a job in 1935 with Immigration and Border Patrol. The agency hired Smithers to document the entire 1,951-mile U.S.-Mexico border from the mouth of the Rio Grande near Brownsville to the Pacific Coast in California.

Smithers photographed the 258 official markers along the border and produced 2,000 images over four months. Along the way, Smithers noticed that local villages always knew he was coming. He attributed this to one of his longtime fascinations—avisos, or flash signals created with a mirror or other shiny object to communicate across distances.

“Every Mexican and Indian I encountered was friendly and knew why I was in their area,” Smithers wrote. “The avisos concerning el fotografo must have increased in frequency and amiability as my trip progressed, for the farther I went, the more friendly the natives were.”

Photo by Brandon Jakobeit

Picture This

View Smithers’ works at these Texas locations

In Alpine, the Museum of the Big Bend employs W.D. Smithers’ work to illustrate regional history. It also explores his legacy with an exhibit on his biography and a sampling of his photos. The Smithers exhibit features one of the lamps he produced at his Alpine shop in the 1940s and ’50s. The base of the lamp is a wooden wagon, and the shade, shaped like a wagon covering, is a picture of cowboys branding a calf. In the museum’s mining exhibit, Smithers’ photos of quicksilver mines in Terlingua show the difficulty of the underground work; and in the frontier exhibit, one photo gives insight into the equipment used by the cavalry. Open Tue-Sat 10 a.m.-4 p.m. on the Sul Ross State University campus, 400 N. Harrison St., Alpine. museumofthebigbend.com

In Terlingua, Smithers photos adorn roadside signs commissioned by Visit Big Bend to depict the history of the area. visitbigbend.com

The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin holds Smithers’ archives, including thousands of photographs, manuscripts, photography equipment, and lampshades. Open to the public Tue-Fri 10 a.m.-5 p.m., Sat-Sun 12-5 p.m.; for private viewing Mon-Sat 9 a.m.-5 p.m. 300 W. 21st St., Austin.

hrc.utexas.edu

By 1936, Smithers had opened a photo shop in Alpine. Initially, he focused on making glass lantern slides of Mexican churches and archeological sites, but he eventually pivoted to photo lampshades to showcase his work.

According to Cook’s thesis, Smithers printed images on a parchment-like material in his kitchen, and his employees colored the prints by hand and laced them onto an iron frame. The shades, which he sold in his Alpine shop and shipped across the country, featured Smithers’ photography of scenes like desert mountains, cacti, and cowboys.

Carl C. Williams, then a Sul Ross College student, got a job printing lampshades for Smithers in his darkroom in 1951. Later, when Williams was sheriff of Brewster County, he visited Smithers daily for two weeks to help him catalog his negatives before selling the collection to UT.

“Whenever I worked alongside him on an assignment or on a job, I always thought I did a pretty good job—until I saw his photos,” recalls Williams, who is also a photographer.

UT administrators heard of Smithers’ massive photo collection from the late Austin-based historian Kenneth Ragsdale, who met Smithers in 1966 while researching Terlingua quicksilver mines. That meeting set in motion the university’s purchase of the collection.

In the foreword to Smithers’ memoir, Ragsdale recounted a visit he made to Alpine to pick up photo boxes and deliver a check to Smithers. “I asked him, ‘Bill, since this is probably the most money you have ever had at one time, are you going to retire?’” Ragsdale wrote.

“Nope,” Smithers responded. “I’m going to buy me a new camera.”