For most lovers of Big Bend National Park, the landscape evokes tales of momentous adventures and jaw-dropping beauty: sweaty hikes to Emory Peak, vistas of rugged mountains extending into Mexico, and sleeping under starry skies. For Austin-based photographer Sarah Wilson, the stories contained within the park are also deeply personal. Her grandfather, the late paleontologist John A. “Jack” Wilson, founded the Austin Vertebrate Paleontology Lab at the University of Texas at Austin in 1949 and spent decades leading digs in West Texas. Wilson’s appreciation for Big Bend encompasses her love for her grandfather and the science behind the park’s seemingly boundless, mind-bending evolution over millions of years.

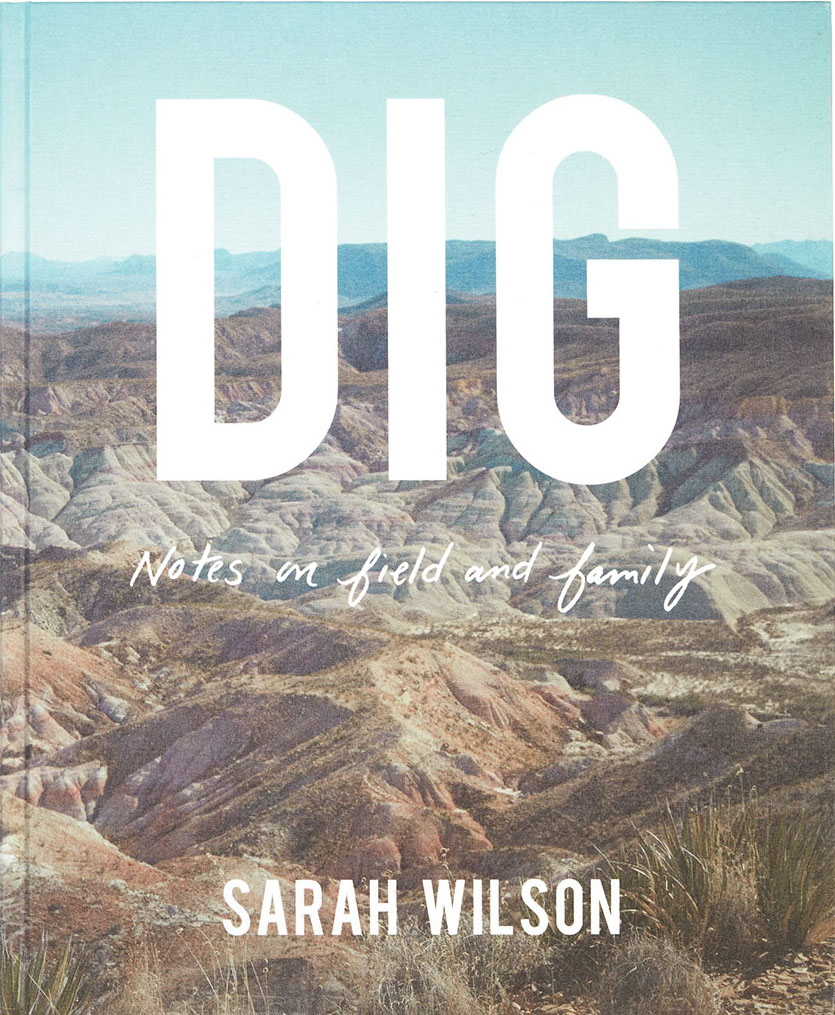

DIG

Find out more about the book and author.

Wilson’s new book, DIG: Notes on Field and Family, is a visually stunning meditation on those interweaving stories, presented through a skillful comingling of photography and paleontology. Wilson’s spare but poignant words guide readers through her striking imagery, bringing them in contact with some of life’s big questions. How do family connections endure over generations? And how does humanity fit into the big picture of time?

DIG sprouted from Wilson’s good instincts. In 2008, she visited her almost 94-year-old grandfather in the hospital. During her early 20s, Wilson had studied photography and lived in Marathon, one of the tiny towns closest to the national park, and began shooting images of the landscape. She brought a large print of an ocotillo from Big Bend and taped it to her grandfather’s wall.

“I was thinking, ‘Don’t you want in the last moments of your life to reconnect with what you’re passionate about?’” Wilson says. “He had been frail and was on a respirator, but when he saw that image, he sat up, reenergized. He knew exactly where I took it because he could see the rock formations in the background. He said, ‘That’s near Castolon Peak.’ It was this super sweet moment. And then he passed away four hours later.”

About a year before he died, Wilson’s grandfather gave her three black metal boxes full of his 35 mm teaching slides. Among the faded Kodachromes were images of rock formations and landscapes from his annual digs in West Texas in the 1950s through the ’80s. Wilson was astonished to find that many were taken at the exact places she had photographed in the 800,000-acre park, some even from identical points of view. Seeking to deepen her connection to Big Bend through the eyes of her grandfather, Wilson decided to return, but this time on a dig.

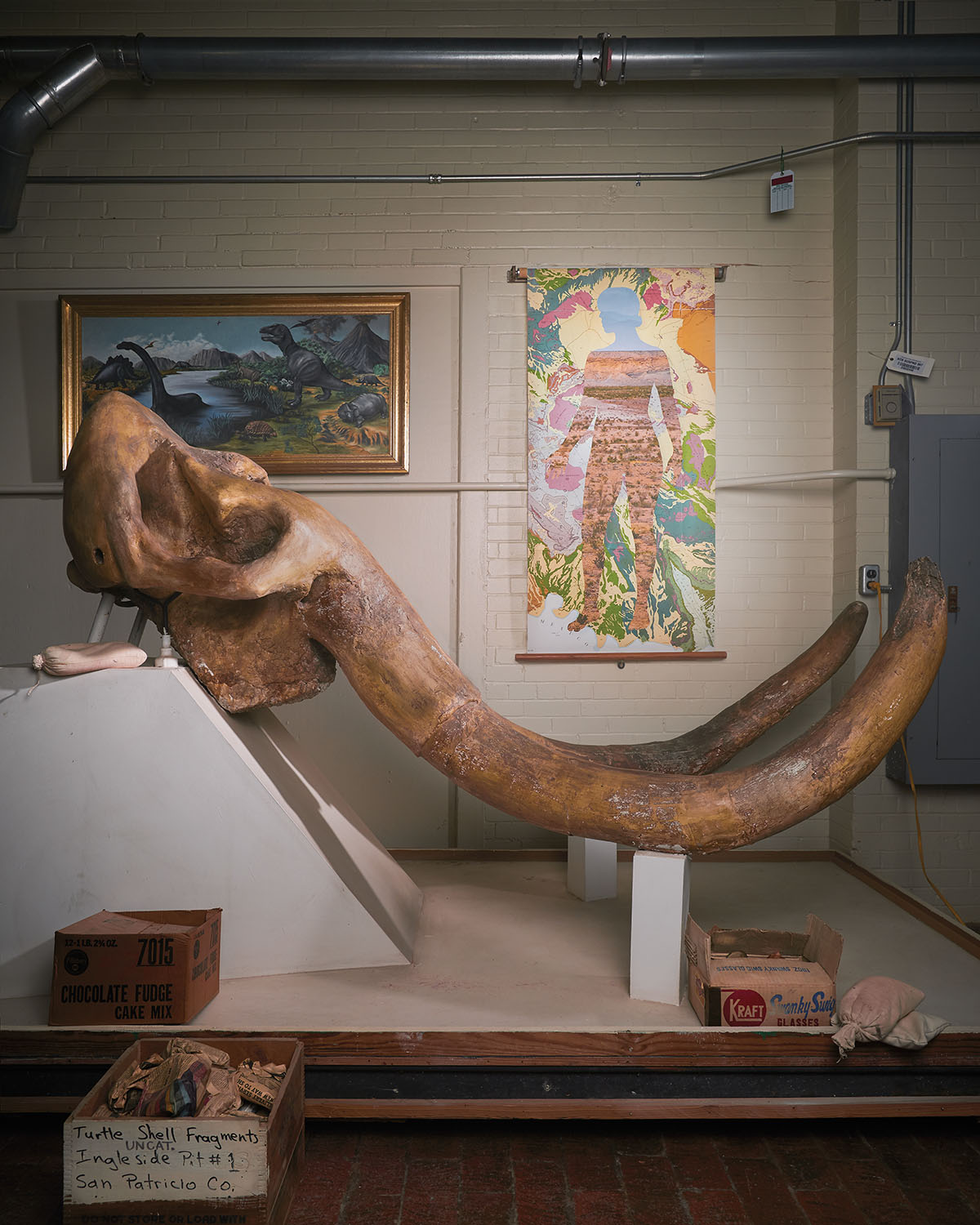

In 2012, she emailed Chris Kirk, a UT professor of anthropology who specializes in biological anthropology. Kirk is one of the few paleontologists to return to the Tornillo Basin of Big Bend, an area of rich paleontological resources in North America, after Jack’s digs there. Kirk’s fossil finds throughout West Texas are curated and stored at the UT lab that Jack founded. Now called the Jackson School Museum of Earth History Vertebrate Paleontology Laboratory, the lab has become one of the most esteemed vertebrate fossil repositories in the country.

“I’d never met Sarah,” says Kirk, who has led students on digs in Big Bend since 2004. “She just showed up one cold night at our field camp on Tornillo Flat as we were limping back from the field. It turned out that she is an absolute beast in the field.”

For the next decade, Wilson and her camera accompanied Kirk and his crew on their digs. Often bringing along her grandfather’s threadbare bandana, Wilson felt her grandfather was her “passport” to understanding this land. Kirk, who met Jack once before he passed, still follows his old field notes. They’re a conduit not only to the land but to what this part of Texas was like in the ’70s, before there was much in the way of infrastructure. Wilson found a receipt in one of her grandfather’s notebooks for a two-night stay with breakfast at the famous Paisano Hotel in Marfa totaling $13.

The son of a painter and sculptor, Kirk says it feels natural to have an artist involved in his digs. “There is a near-universal, gut feeling that people get when they take time to think about what has caused these things to be the way they are. We are looking at processes that operate on the time scale of the rising and eroding away of mountain ranges. It almost sets you outside of your ego. And that’s a perfect place for art.”

DIG is a visual portal into Big Bend’s geological history and the people who try to understand it. In its pages, we see Wilson’s bespectacled grandfather in a pearl snap Western shirt and bolo tie, his eyes sparkling. We see his major find, Rooneyia viejaensis, a skull he unearthed in 1964 that is one of the most complete fossil primate skulls ever found in North America. And we see vivid images of her grandfather’s notebooks.

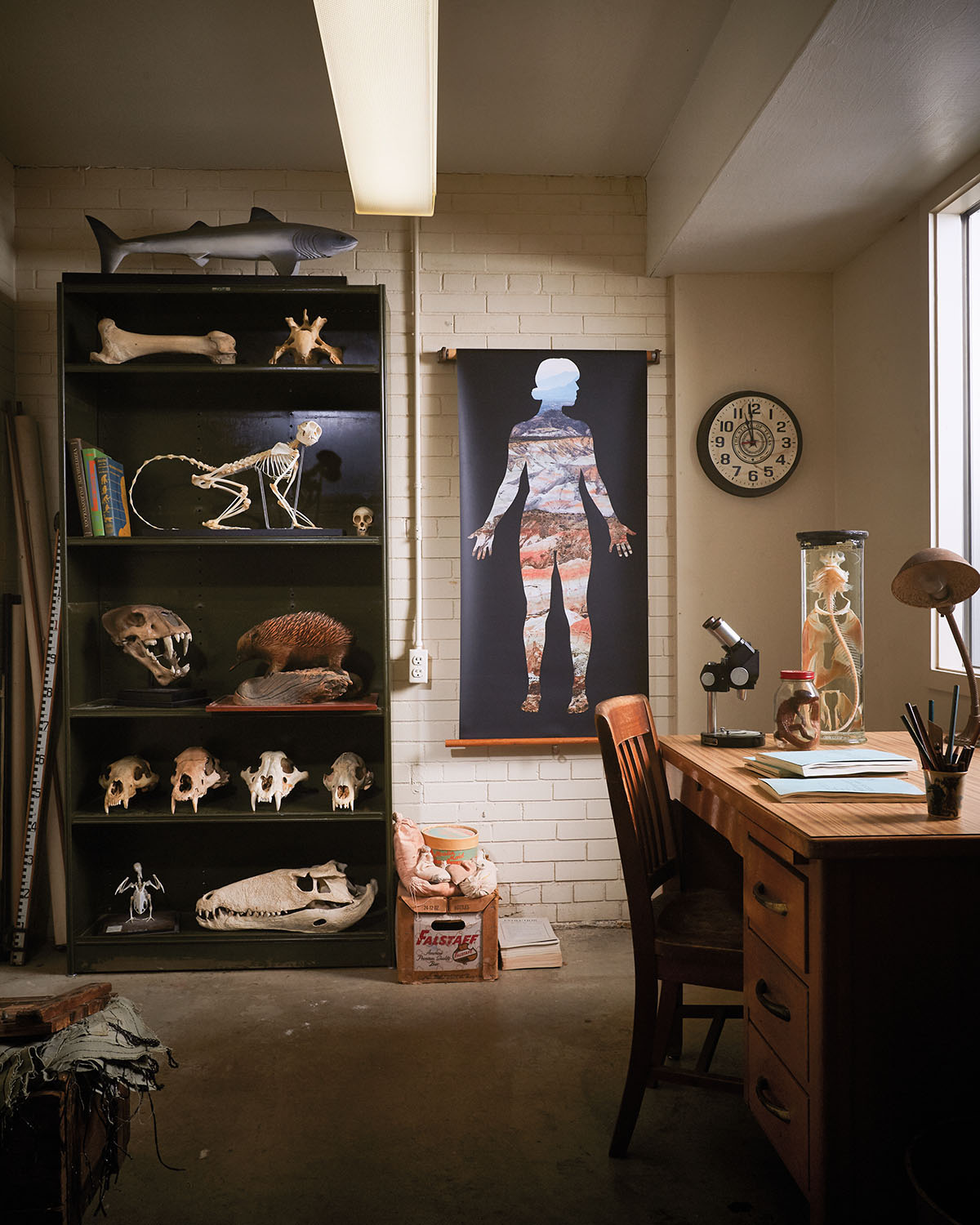

Wilson exemplifies Kirk’s freeing of the ego via her playful photographs of her own silhouette infilled with topographical imagery from Big Bend. These photos are printed on scrolls resembling the vintage pull-down human anatomy maps once used in science classes. “I wanted to somehow describe what it feels like to be in that landscape,” Wilson says, “so I imagined the landscape taking over my body in a sense, or kind of ingesting it.”

Dig Deeper

To learn more about geology and paleontology in Big Bend, visit the Fossil Discovery Exhibit. Visitors can experience a life-size replica of the 18-foot-long flying Quetzalcoatlus discovered in Big Bend National Park—the second-largest known flying creature to have existed.

fossildiscoveryexhibit.com

Opening night of DIG: Notes on Field and Family, Wilson’s exhibit at Do Right Hall in Marfa, is scheduled for June 1.

wrongmarfa.com/do-right-hall

Wilson is also slated to speak at the Agave Festival Marfa on June 2.

agavemarfa.com

Images of the scrolls are included in the book, but they are also stand-alone art pieces that will be on display indefinitely beginning June 1 at Marfa’s Do Right Hall. The event space is in a converted adobe church built in 1886 with soaring 14-foot ceilings. The exhibit will include images from DIG as well as a 16-foot-long collage on wood of Big Bend photos Wilson took with her grandfather’s camera, backlit 30 mm slides of her grandfather’s images, bones from the paleontology collection, and a glass cast of a saber-toothed cat skull. “I think there’s a huge educational opportunity documenting the bones and geology of this beautiful area—things often overlooked or that never occurred to people,” gallery owner Buck Johnston says.

Wilson considers herself lucky to work in the middle of nowhere, looking through a window into the history of our planet. Every time she finds a bone, she considers the body it was connected to and the environment it lived in. “You are in a place that has changed so much over all those eons,” she says, “and you consider everything that had to happen to get us to the beings we are now.”