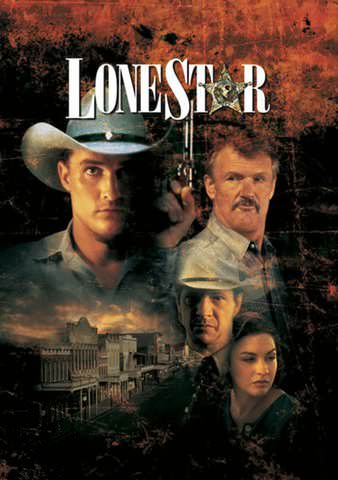

Actor Matthew McConaughey plays Deputy Sherriff Buddy Deeds in the neo-Western Lone Star. Photo courtesy Columbia Pictures

John Sayles is one of the great American independent filmmakers. His epic 1996 drama Lone Star, which received a new release from The Criterion Collection this month, is one of his masterpieces. Channeling 1970s neo-noirs like Chinatown as well as the epic ensemble dramas of Robert Altman (Nashville), it’s a muckraking mystery set in a Texas border town, following recently elected sheriff Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper), a lifelong resident, as he tries to figure out what happened to a previous sheriff, the brutal and corrupt Charlie Wade (Kris Kristofferson). Charlie ran the place a generation earlier alongside Sam’s dad, deputy sheriff Buddy Deeds (played by a then-obscure actor named Matthew McConaughey) and was believed to have disappeared after absconding with $10,000 in county funds. The discovery of Charlie’s badge in the ground at a shooting range suggests foul play and ignites an investigation that turns over every stone in town—and several across the border.

Photo courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Together with his longtime co-producer and wife, Maggie Renzi, Sayles made a string of films in the 1980s, ’90s, and aughts in the vein of Lone Star: intelligent, observant low- to medium-budget dramas about people and places that could actually exist, set in a variety of times and places, operating in an impressive array of film genres, from the sci-fi racial metaphor (Brother From Another Planet), the labor drama (Matewan), and the period sports film (Eight Men Out) to the fable (The Secret of Roan Inish), the East Coast big city potboiler (City of Hope), and the wilderness survival story (Limbo). On top of whatever else is going on in them, Sayles’ films are about the construction and evolution of society, scrutinizing the morals and codes of the characters, and the role that self-serving myths—and outright lies—play in maintaining entrenched power structures. Lone Star is one-stop shopping for Sayles’ aesthetic, as well as one of his most sheerly pleasurable works, thanks to its deadpan humor (an older character says, “At my age, you learn a new name, you gotta forget an old one”) and its clever storytelling, which moves the viewer between past and present with transitions where the camera moves to reveal a time period, like a rotating set in a stage play.

The gregarious Sayles was happy to revisit the writing and filming of Lone Star, one of the achievements he’s proudest of. Along the way, he talked about his fascination with official histories and competing narratives, the tension between Texas and Mexico, and the relationship between cuts in a film and borders on a map.

Texas Highways: What was the genesis of Lone Star?

John Sayles: I had hitchhiked through Texas a bunch of times. We had some friends in Austin, we had some friends in San Antonio, and I had grown up watching the Davy Crockett and Alamo stories according to Disney and John Wayne. And then as I did a little bit more research into it, I thought “Oh, this is a lot more complicated than that.” Then I wrote a movie for Roger Corman called Piranha. They ended up shooting the movie in Aquarena Springs, not too far from the LBJ ranch, and they called me down there to do some rewriting and to do a cameo.

I had one day off between the work I was doing down there, so I took the bus down to San Antonio and finally went to the Alamo. And at the same time, there was a protest march circling it, consisting of Chicano Americans saying, “Why don’t you tell the whole story?” I talked to some of them and they said, “Well you know, this version does tend to leave out some of why the Texans were really fighting for freedom, and a lot of it was because Mexico had outlawed slavery. These guys wanted to get rich and they felt like outlawing slavery was really gonna cramp their style.”

TH: When I was growing up in Dallas, we had Texas history classes. I don’t remember the issue of slavery coming up.

JS: Yeah, and it didn’t for a long time. The official story left that out. Also, did you know there were Mexicans inside the Alamo? That’s the other part of the story that gets left out, which is that [Mexican president] Santa Anna was no day at the beach. There were a lot of Mexican people living in Texas that were like, “Oh no—that guy? He’s gonna come up here? It’s fine when he’s really far away down in Mexico City, but if he’s coming up here and telling us what to do, we’re not having it.” It was a complicated story.

TH: How did the difference between the myth and the actual story of the Alamo feed the screenplay of Lone Star?

JS: I felt like, what if I get into a family secret and family business, but that’s all a metaphor for this bigger thing, which is the question, “What happens when your legends are not useful anymore, they’re actually holding you back?” To move forward, you’ve really got to examine your legends and revise them toward the true complexity of the situation. I’ve spent a lot of time in the American South, and most of those states now have done that with the Confederate flag. They’ve kind of gotten it: “OK, that was an important part of who we said we were and everything, but now let’s examine it a little bit more.” Texas is more complex than people want to think.

TH: Was this the biggest film you’d made up until this point?

JS: Yeah. I think Matewan is about the same size just in the number of characters. But doing some of those time transitions without a cut made it a little more difficult. And, we were shooting widescreen. Widescreen looks great for a Western but it’s hard on the art department, because you’ve got more stuff to fill up the frame if you’re shooting an interior [scene]. You just see more. So it was a lot of planning, a lot of work. But I had a very good crew. Stuart Dryburgh, who shot it, did a great job. We also learned a lot during the prep period that deepened our understanding of the story.

TH: What kinds of things?

JS: Well, the drug [smuggling] thing was already becoming a problem. But the narcos hadn’t hit that part of the border yet. I actually played a border patrol guy in the movie and they cut the scenes out. But what’s interesting is, on those days [when we were shooting my scenes] in Eagle Pass, the border patrol guys told me, “The thing we say most often is, ‘Don’t make me run,’ or ‘¡No me hagas correr!” They’d come over to the van and then they’d check to see if the [driver] had any criminal record in the United States, and if they didn’t, they literally drove them over to the other side and let them out of the van: See ya later! Maybe tomorrow! So it was this kind of game. They weren’t wearing body armor. There was just a different vibe, and that all got into the movie.

TH: That school board scene hasn’t dated even a minute.

JS: Most of the actors in that scene were Texas actors. At that time, anyway, if you lived in Texas, you were considered “local,” and so people were driving 300 miles to do a “local” job. They’d all been in Walker: Texas Ranger, sometimes two or three times. So it was kind of a reunion of Texas actors. They said, “Yeah, we’ve lived through this stuff, we know what we’re talking about in this scene.” Very often when you shoot a scene like that, you try to have actors not overlap each other, for sound, but they were all so good together that I said, “We’re gonna mic this like a Robert Altman film, so you can all jump on each other. Just let the heat of the moment go.”

TH: It really felt like this incredible burst of documentary in the middle of fiction, like something in a Ken Loach movie. The late, great Hal Ashby also used to do scenes like that in his movies, like the rap sessions in Coming Home, where he just shot actual Vietnam veterans talking about their experiences.

JS: I have a story about Coming Home. John Schlesinger, the guy who directed Midnight Cowboy, was originally going to do Coming Home, and at the last moment he chickened out and the producer just freaked. Schlesinger walks down the beach in Malibu and finds Hal smoking in his hot tub, and says, “I want you to read this script and see if you’ll do it for me.” Two hours later Hal says, “Yeah, I should do this.” So the director came in very, very late in that process. The casting had pretty much been done at that point.

TH: Seems like so much could have gone wrong, with the director who’d raised the project up suddenly abandoning it, and a new director with a very different sensibility jumping in.

JS: Yeah, but you know, sometimes the energy of a film, if the time is right, takes care of all that, in a way. There’s a lot of luck in making films. Sometimes you just get lucky. For instance, when we did our Texas casting, Vanessa Martinez, who plays the Elizabeth Peña character as a young girl, was a 15-year-old when she came in to read. We had her read for three different parts, and every time it was like, “Who is this?” No training! Just a kid who wanted to be an actor. I worked with her three more times. And we just walked into that.

TH: You have a number of people like that in your cast, including Matthew McConaughey, who just showed up in your movie out of nowhere and made people go, “Who the hell is that?” Right after that, he landed the lead role in A Time to Kill, which made him a star.

JS: Matthew had only done Dazed and Confused. When we read Matthew, we just felt like, “Geez, he’s from Uvalde, Texas, and he can wear the hat and the boots! And we need a guy who can go toe-to-toe with Kris Kristofferson, who’s also a border Texan guy.” Not too many actors had all that. The great thing about Matthew is, even though you know the guy’s just got this charisma, he’s a hard-working actor as well. It was great to work with somebody where you just knew: He’s gonna hang around. This is not a short-lived phenomenon.

TH: Elizabeth Peña, rest in peace: also amazing. Can we talk about her?

JS: I’d seen Liz in a bunch of things and just thought she was terrific. We were lucky to get her to do it. Actors have different kinds of rhythms to how they do it, and Liz Peña is someone who was great on her first two takes – she just had great instincts – but then she would complicate it a little bit. So when she was working with Chris Cooper, I just said, “We’re always gonna start with a camera on Liz, and she’s gonna knock it dead.” She was very funny, and so it was a lot of fun to work with her.

TH: You also got a lot of mileage out of Clifton James, who was one of the go-to 1970s character actors.

JS: Cliff was a wonderful actor. He could play an everyman guy, and he had that wonderful voice. He’d do these little, subtle things, and I just thought “OK, this guy has the bluster, but there’s also a guy underneath it who can have some subtext.”

TH: What made you want to cast Kris Kristofferson as Charlie Wade, one of the meanest, most corrupt cops in movie history?

JS: A lot of it was that Kris was a Texan, and he had that comfort level playing that guy. I always felt he was kind of an underrated actor and thought that I’d like to see him play a bad guy. He always joked that when his wife read the script, she said “Finally, you’ve been typecast!” Which wasn’t true at all! And he had those eyes, almost like a Laplander. I just felt that if Kris Kristofferson gave you a stare, you’d be scared.

TH: What do you like about master shots, where the camera is moving from one character or group of characters to another and there aren’t a lot of cuts?

JS: A cut says, “Here’s one thing—and then, on the other side, here’s another thing.” When I don’t have a cut it’s saying, “Guess what? These characters may not know it, but they’re not separate. This group and that group, there’s not a hard line between them. The past and the present: there’s not a hard line between them.”

TH: In Lone Star there are many configurations of parents and children. How did that allow you to structure the story of the film, and articulate the themes?

JS: It’s a good metaphor for our official story. Our parents tell us “this is how things work,” our teachers tell us “this is how things work,” our newspapers tell us “this is how things work,” our government tells us “this is how things work.” And as children, you either say, “OK, I got it. I’m gonna try to live up to that,” or you start to ask questions and challenge things.

Through fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, and all that, I’m gonna tell a story about a place, and the past and present in this place, and how they’re connected through these families, and through what was handed down—and the main character is gonna be the Oedipus character.

TH: How about the idea of borders, which is a big element in Lone Star?

JS: One of the things that people think about the border is that Americans live here and Mexicans live there. No. If you go to the border in Texas, in most of those towns, people speak Spanish at home and they speak English in school. English is their second language. In Eagle Pass when we were there, all the Anglo dentists practiced below the border because the insurance for malpractice was so much less in Mexico than in the U.S. You could be an Anglo person and go to an Anglo dentist, but you did it in Mexico, because it was gonna be two-thirds to half of the cost that it would be in the U.S. The border is there for a political reason. For people who live on the border, often their jobs exist because there is a border. There are things that you can get on that side of the border that you can get on this. Maybe there’s an advantage to being on the border because you can get cheap materials. Communities on borders have always been fascinating places to me.

TH: You get into the idea that the border is itself an illusion. A character in Lone Star even comes out and tells us that—and it’s a Native American, probably not coincidentally.

JS: Yeah. If you’re Kickapoo or Tohono O’odham, you live on both sides of the border and you get to cross because of your reservation. The Mohawk people up in New York state can cross the bridge [into Canada]. They could cross any time they wanted to because it was part of their land, part of their deal, so that line means a very different thing to them.

TH: All this talk of the border is making me think about what you were saying about the cut. The cut implies, Here’s one thing, and then over here, there’s another thing. A cut is a border. If you don’t have a cut or a border, it’s sending the message, “This is all one thing.”

JS: It’s why we did some of those 360-degree shots in Lone Star. There’s a certain amount of work involved in doing shots without cuts, or as you say, without borders. But they’re very satisfying when you make that transition. It’s not something where there’s a line between the person now and what’s going on then. Another thing is, really, most of the people who are telling a story are telling their version of the story. I did a few tricky things with those kinds of scenes. There’s one transition where a woman on a porch starts telling a story and when you come back from the [flashback], Chris Cooper’s there, but he’s in the bar that the story was set in, and he’s talking to yet another person who was also there that night.

TH: What’s that about?

JS: It’s about the idea of a shared history. People have their different versions, but they actually jive on some parts of a story.

TH: What are you and Maggie working on at the moment?

JS: We’re trying to make a Western now and have been trying to raise money for several years. It’s not political at all, but I’m interested in making a Western that talks about values, and it’s one of the things that Westerns used to be good for.