Courtesy The Wittliff Collections

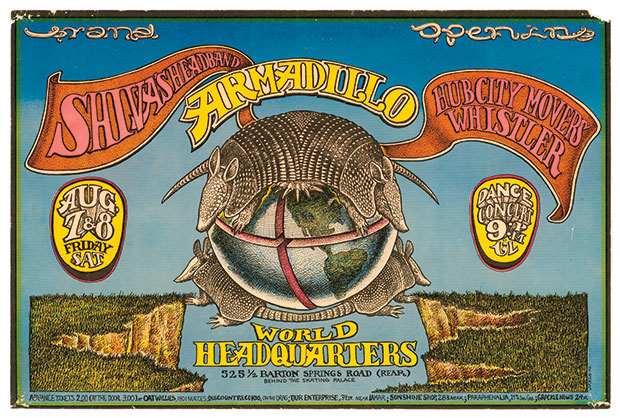

During Austin’s counterculture heyday, from the opening of the Vulcan Gas Company in 1967 to the closing of the Armadillo World Headquarters in 1980, a concert wasn’t a reality until it was advertised with a mind-blowing poster. The images and information went together like words and music to create a siren song for fans.

HOMEGROWN: Austin Music Posters, 1967 to 1982

The exhibit runs through July 3 at the Wittliff Collections, located on the 7th floor of the Alkek Library at Texas State University in San Marcos. Hours are 8-5 Mon-Wed and Fri; 8-7 Thu; 11-5 Sat; and 2-6 Sun. Free. Call 512/245-2313.

But as exemplified by the exhibit HOMEGROWN: Austin Music Posters, 1967 to 1982, which runs through July 3 at The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos, the flat artifacts of anticipation have become, in most cases, the last thing standing. Clubs close and are torn down. Bands break up. But posters endure as history to admire.

With music by the bands featured in the posters gently piped in, the multiple exhibition rooms are filled with recordings for the eyes. One hundred and forty vintage posters recall the consecutive musical eras of psychedelia, blues, progressive country, and punk/new wave that gave Austin its reputation as a live music mecca. The worst thing about seeing a band in a club is that when the show’s over, it’s over. (Also, sometimes one of the best things.) But a poster is a lasting excuse to daydream back to your skinny-jeans days.

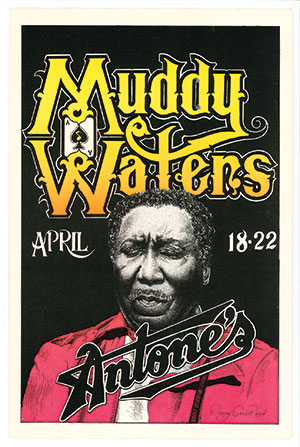

Great music inspires creativity of all kinds, and the visual artists of the Texas capital were drawn to sheets of paper where they could create visual music. Clubs catering to a range of genres—from the hippie-blues-country mix at the Vulcan, Armadillo, and Soap Creek Saloon, to the blues at Antone’s, and the new wave scene at Raul’s and Club Foot—hired such posterfarians as Micael Priest, Danny Garrett, Kerry Awn, Guy Juke, Ken Featherston, and Sam Yeates to make their shows seem cooler. These are just a few of the artists whose posters hang at the Wittliff.

A concert wasn’t a reality until it was advertised with a mind-blowing poster.

Also well-represented are the pioneers of the Austin poster scene: Gilbert Shelton, the original Vulcan art director, and Jim Franklin, who would replace him in ’68, when Shelton moved to San Francisco and launched his underground comic “The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.” A spirit of unity among the artists far outweighed any competition, Franklin said. “There was no trace of jealousy or animosity between the artists,” he said. “That comes with lesser talents. We just loved art and felt like we were all in it together.”

Though the accepted chronology has Austin artists following San Francisco’s lead, the first “’60s underground comic” was actually produced in Austin by artist and historian Jack “Jaxon” Jackson in 1964. Jackson’s “God Nose” came out four years before the first Zap Comix hit the streets of San Francisco. Jackson’s artwork and copies of The Ranger, the University of Texas’ irreverent magazine that unleashed Shelton, greet you in glass cases as you enter the exhibit. The beginning is always a good place to start.

As during its time of focus, Homegrown is rich with images of armadillos, the local hippie-slacker symbol that set Austin apart from the Haight-Ashbury scene of national obsession. The ’dillo was Franklin’s doing. In 1968, he was hired to draw a poster for a “love-in” concert at Wooldridge Park and was thumbing through a zoological guidebook when he came across an armadillo. That was the critter, that rat with aluminum siding, that years before had nearly scared the life out of a 10-year-old Franklin when one ran between his legs on a hunting trip with his dad. Franklin drew a ’dillo smoking a joint—an image included in the exhibit—thereby creating a new mascot for Austin’s weirdness. Surreal visions and lighthearted irreverence, such as Yeates’ tiger with the guitar neck tongue for a Bob Seger concert, gave Austin’s poster scene its own identity.

The image always came first for Franklin and the others, with the details of time and place included at the poster’s bottom or edge. “The music was the castle, separated by a moat,” Franklin said. “Then came the village, the marketplace. Every time I drew a poster, it was made so that the information could be cut out and the rest could stand alone as a work of art.”

The image always came first for Franklin and the others, with the details of time and place included at the poster’s bottom or edge. “The music was the castle, separated by a moat,” Franklin said. “Then came the village, the marketplace. Every time I drew a poster, it was made so that the information could be cut out and the rest could stand alone as a work of art.”

The rooms of the exhibit are divided into five groupings, starting with Vulcan Gas Company and psychedelic images touting bands such as Conqueroo and Shiva’s Headband. The “Blues Portraits” section highlights the importance of blues to the development of Austin’s music scene, featuring drawings of musicians like Muddy Waters, Freddie King, and Mance Lipscomb. The stroll continues with a room devoted to “Reimagining Texas,” which is the umbrella shading such genre-bending Austin acts as Willie Nelson, Doug Sahm, Freda and the Firedogs, and Greezy Wheels, who mixed musical styles and substances to create a new kind of country groove.

Another exhibit area contains a host of posters for “Traveling Bands,” from the Grateful Dead to Taj Mahal and Bruce Springsteen. The last stop on this Austalgia train is a smaller area featuring posters of the “Punk and New Wave” scenes of the late 1970s and early ’80s, the prime time of local bands like the Big Boys, the Dicks, and Joe “King” Carrasco.

But your journey through Austin’s glory years isn’t over when Homegrown ends. Next door, The Wittliff Collections’ exhibition Armadillo Rising: Austin’s Music Scene in the 1970s features some of the best Willie Nelson memorabilia available, including a songbook of tunes he’d written by age 11. The two shows go together like queso and jalapeños on the famous nachos at the Armadillo World Headquarters.