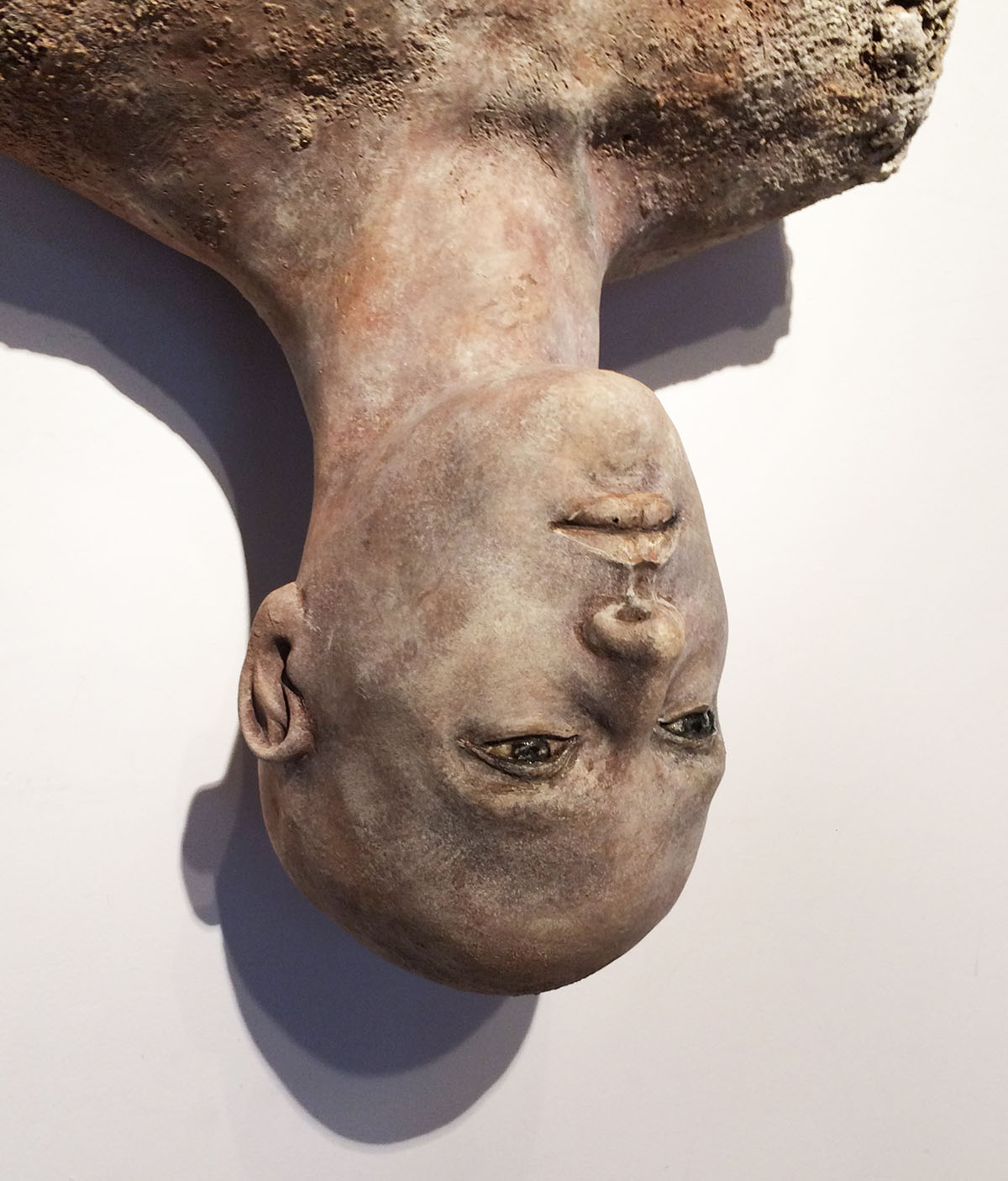

One of the clay works by Alejandra Almuelle on display in The Many Shapes of Texas Clay. Photo courtesy Rockport Center for the Arts.

If there’s an art form that’s been misunderstood, it’s clay art.

“There is a bit of history of clay being the low form in the art world due to its functionality,” says Stan Irvin, who taught ceramics and clay figure sculpture at St. Edward’s University in Austin for 38 years. “It had a lot to prove to the art world, that clay had the potential to be art. It’s not a matter of the medium that makes it art, it’s what you do with it.”

Irvin, who now maintains a studio and gallery in Rockport, adds that another strike against clay is that it can be a challenging medium. “Clay is the only artform I know where you can spend hours on something that blows up in the kiln,” he says. “Clay has abundant opportunities for failure, but is also very gratifying. The possibilities of what you can do creatively are endless.”

These challenges and possibilities tend to bring clay artists together, and Texas has a thriving community, including a wealth of artist’s groups, studios, and shows.

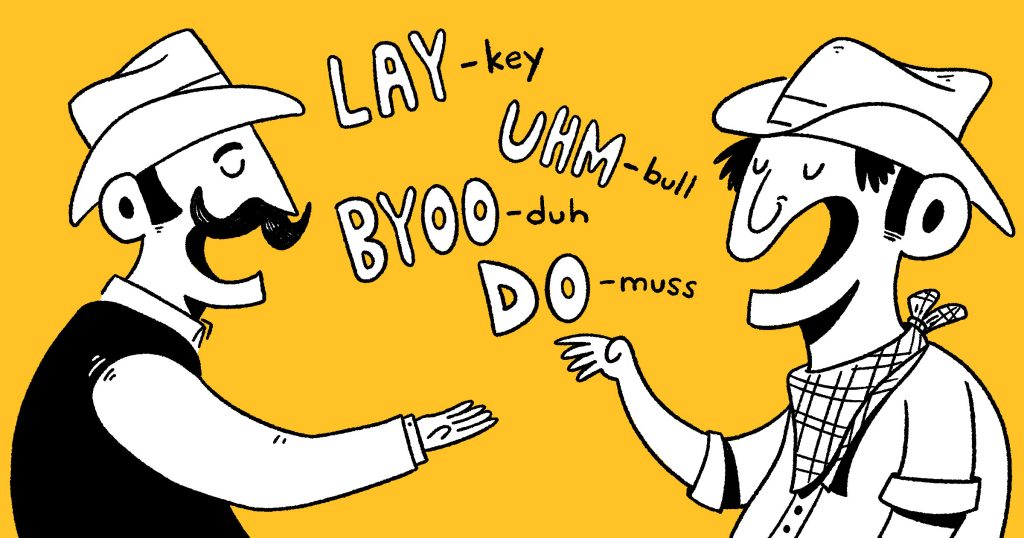

One of those, a three-part exhibition at the Rockport Center for the Arts, runs through Feb. 28 (with appropriate precautions including limits on admission and requirements for face masks and social distancing). The main show, The Many Shapes of Texas Clay, features four Texas clay artists, Alejandra Almuelle and Rory E. Foster from Austin, Roy Hanscom of Houston, and Irvin. The second exhibit, Rockport Clay Artisans, displays work from aspiring local artists, and the third, recent work from the center’s members.

“We cancelled our annual clay fair but decided to have an exhibit that highlights how clay is used across the state,” curator Elena Rodriguez says. “Clay as an art form is accessible—everyone plays with clay or play dough or mud as a child.”

Planters by Rory E. Foster. Photo courtesy Rockport Center for the Arts.

Hanscom, a ceramics professor at Lone Star College-North Harris in Houston, says the material sets no limit in its ability to adapt to ideas and designs. Clay itself comes in many forms and is found all over the world. Years back, artists sometimes built studios near a source of clay, Irvin says. Today, most work with a mix of five or six different clays from various locations, according to their particular need and the characteristics of the clay, including texture and color.

Another annual event, the Texas Clay Festival, was first organized in 1992 by five couples who were unhappy with the available opportunities to show their work.

“We wanted a show where the artists were in charge and that focused on clay in Texas,” says one of the founders, Jon Brieger. The event now involves more than 80 Texas artists. “We’re part of the broader community and we all have different influences. It’s a wide range of people, from those doing sculptural work to functional dinnerware. We try to keep a nice mix.” This year’s festival is scheduled for Oct. 23-24 in the Gruene Historic District of New Braunfels.

Clay art also appears in studios in almost every Texas city. Among more formal options, the permanent collection at the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts has what Irvin calls one of the best contemporary collections of clay art in the country. Following a 2019 exhibit at Stephen F. Austin State University that featured contemporary Caddo art, including ceramics, the Caddo Nation is partnering with Caddo Mounds State Historic Site in East Texas to give lectures and demonstrations on a variety of topics, including clay art.

“Despite the size of the state, there is so much community and interaction among clay artists,” Irvin says. “You probably can go to any town of any size and find a potter’s association or some group of artists that support each other and gives them an opportunity to show their work.”