Many people assume Amy Borgens’ job is full of action and intrigue—she’s heard her share of Indiana Jones references. But unlike the world’s most famous on-screen archeologist, the state’s only marine archeologist is not running around with a bullwhip and outsmarting Nazis in search of a stolen idol. “It’s not Raiders of the Lost Ark,” says Borgens, who is employed by the Texas Historical Commission.

While Borgens keeps her finds top secret, she was willing to invite me to her quiet, landlocked office in East Austin. Her desk is decorated with a Wonder Woman figurine and a skull and crossbones coaster. There are model ships, ship bookends, and paintings of vessels thrashing in the ocean. There is also a wall of tall shelves crammed with tomes on maritime history, with titles like Art and the Seafarer; The History of the American Sailing Navy; and Sea of Mud: The Retreat of the Mexican Army after San Jacinto, An Archeological Investigation. All those books and nearly three decades of experience have made Borgens a revered figure on preserving, documenting, and caring for artifacts found in Texas waters.

“Everyone expects the east and west coasts to have a rich maritime history, but what I love about the Gulf and the Texas coast is that it was the last area of U.S.territorial competition between Mexico, Texas, and Europe,” Borgens says. “It was the conclusion of ‘from sea to shining sea.’All the major powers had a presence in the Gulf.”

Part of Borgens’ job is to monitor activity and prevent people from pilfering the more than 180 official shipwreck archeological sites, as well as undiscovered sites throughout the state. The drama is usually reduced to making phone calls, alerting authorities, and ensuring a site remains uncompromised. Borgens says she’s had pawn shop dealers and recreational divers call her to try to uncover the location of wrecks, but to no avail. She’s also coordinated efforts to stop tourists, residents, and passersby from taking artifacts once a shipwreck becomes visible.

“She’s kind of a one-woman show,” says Keith Reynolds, a Boca Chica resident and amateur archeologist. Reynolds met Borgens when he rescued a ship mast that was perched outside of an abandoned local convenience store. As a history buff and member of the Texas Historical Commission’s volunteer-based Texas Archeological Stewardship Network, Reynolds recognized the value of the piece and contacted Borgens.

It turns out, the mast was illegally taken from a wreck, likely by a citizen who had no clue the state has some of the strictest laws in the country regarding the disturbance of historic sites. In 1969, the Texas Legislature established The Antiquities Code of Texas, a law created after a 16th-century Spanish treasure ship was plundered, and historic items were lost.

Borgens was an integral member of the team that excavated La Belle and prepared it for display at the Bob Bullock Museum in Austin.

The low visibility of the Gulf keeps most shipwrecks hidden, but clear waters can be problematic. “High visibility brings untoward interest,” Borgens says. “People think it’s finders keepers, and they equate shipwrecks with treasure. But that’s actually rare.”

Reynolds has since become Borgens’ eyes and ears along the South Texas coast. Over the years, hurricanes have exposed timbers and planks from shipwrecks long buried by the sand. Reynolds has discovered several. “It doesn’t belong to any one person; it belongs to all the people of Texas,” Reynolds says. “It’s very important to preserve history because not everything is written down.”

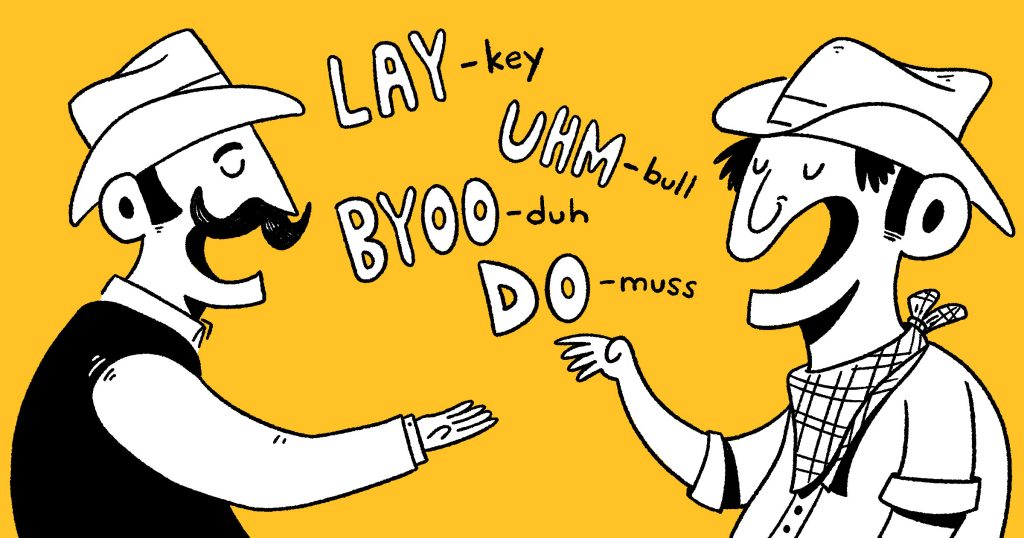

Long before Borgens met Reynolds, she worked at the Conservation Research Laboratory at Texas A&M University. Borgens served as a photographer, radiographer, and videographer during an effort to preserve one of the state’s most famous shipwrecks, La Belle, which sank in Matagorda Bay in 1686. The ship was one of four commandeered by the French explorer La Salle. Members of the Texas Historical Commission discovered it in 1995, and it took decades to inspect and log more than 1.8 million artifacts. The reassembled ship, an impressive display of maritime history that was submerged in Texas waters for over 300 years, now sits in Austin’s Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum.

Andy Hall, a Galveston-based member of the Texas Archeological Stewardship Network, first met Borgens when they were investigating Will O’ the Wisp, a Civil War blockade runner that surfaced after Hurricane Ike. Borgens came up after her initial dive and immediately told everyone the ribs of the ship were spaced unusually far apart and the hull plating was unusually thin, both of which were key factors in identifying the vessel. “She said that right off the top of her head,” Hall says. “It’s hard for me to imagine anybody better suited to her job.”

Borgens doesn’t dive much anymore. But when she does go out on the water, she rides on a boat “back and forth at about 5 knots” over a potential wreck site, conducting remote sensing surveys to try and detect a vessel. For every La Belle, there might be a 1940s barge at the bottom of a lake or a large World War I ship lurking at the bottom of the Neches River, under a freeway overpass.

As a fifth-generation Texan with an ancestor who fought in the Battle of San Jacinto, Borgens says her interest in the state’s history is “personal and professional.” When she’s alerted to a potential new site, she grabs her “Inspector Gadget case” full of measuring tools, photography scales, supplies for drawing, photo backdrop cloths, writing utensils, fishing line, a Dymo label maker, and a small dry-erase board for labeling artifacts and photos. “I always try to be prepared,” she says.

Borgens sources her inspiration to parents who collected antiques. She also remembers her excitement as a child when her mother took a college class and came home to tell Borgens and her sister all about the paper she was writing on Mayan archeology. Young Borgens was obsessed with the King Tut exhibit that toured the country in the late 1970s. Then, of course, there was the Titanic.

“I had a model Titanic,” Borgens says. “A lot of kids read Beverly Cleary, and I was reading about the Titanic and the Lindbergh kidnapping and Jack the Ripper. I was one of those kids who really liked history class.”

Now Borgens is the authority in Texas on shipwrecks. Find some timber poking out of the sand on a Padre Island beach? Call Borgens. Not sure what to do about that strange coin that washed up on the shores of the Gulf? Borgens can help.

“So much is still unknown, and archeology is often like detective work,” Borgens says. “My job is controlled chaos, and one phone call can change my whole week.”

Raised From the Dead

Visitors to the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin can observe the hull of the famed shipwreck La Belle, which sits on an elevated platform as the centerpiece of the museum’s Texas History Gallery. There are also artifacts recovered from the wreck and an opportunity to interact with the ship via augmented reality. thestoryoftexas.com

The oldest scientifically excavated shipwreck in the Western Hemisphere is displayed in the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. In 1554, two Spanish ships wrecked off the coast of Padre Island. Today, visitors can check out part of San Esteban’s wooden keel, plus silver coins, gold bars, and weapons recovered from Espíritu Santo. ccmuseum.com