Dr. John Sutherland would have died in the Battle of the Alamo had William Travis not dispatched him as a messenger to Gonzales. Years later, in 1849, Sutherland settled east of San Antonio on Cibolo Creek, opened a stage stop at the juncture of the Chihuahua and Goliad roads, and incorporated nearby sulfur springs into his medical practice. As the community bearing his name took root, Sutherland honed his steam and herb system of medicine, reportedly treating cholera and other maladies with some success.

Fortified with a variety of minerals and elements, the medicinal bubbly was prescribed for wide-ranging ailments.

A half-century later, a new Sutherland Springs arose along Cibolo Creek with a hotel and an immense sulfur water swimming pool. Known as “The Carlsbad of America” and “The Saratoga of the South,” the spa drew health-seekers from far and wide, though the local population never topped 1,200. Ironically, too much and too little water helped end the site’s resort days, along with developers’ legal woes. “A flood destroyed much of the resort in 1913,” explains Richard McCaslin, author of Saratoga Springs, Texas: Saratoga on the Cibolo. “And the springs quit flowing when the water table went down after 1920.”

Sutherland Springs was one of many alternative “Saratogas” and “Carlsbads” across Texas. West of Fort Worth, Mineral Wells was known as the place “Where America Drinks Its Way to Health.” Near Waco, Marlin beckoned as “The South’s Greatest Health Resort, Where Life-Giving Waters Flow.” In San Antonio, the Hot Wells resort touted its steaming water as superior to the fabled waters of Europe. Natural spas also bubbled up in Wizard Wells, Stovall Hot Wells, Indian Hot Springs, Glen Rose, and Sour Lake.

Nineteenth- and early 20th-century health-seekers drank and bathed in mineral water both hot and cold. Fortified with a variety of minerals and elements, the medicinal bubbly was prescribed for wide-ranging ailments, from backaches to cancer and diabetes. Medical opinions on the healing springs sometimes diverged. But many doctors—both classically trained and “alternative” healers—believed in the waters’ efficacy, and like Sutherland, established their practices where mineral water was available.

The people of Marlin did not immediately perceive the natural-health bonanza that gurgled from their soil. When the Falls County seat drilled a new well for potable water in 1892, locals grimaced at the odiferous sulfur water that shot from the earth at 147 degrees. According to various accounts reported in early 1900s editions of the Marlin Democrat and Texas Magazine, a stranger discovered the hot water’s therapeutic benefit when he repeatedly plunged into an old linseed barrel of hot well water, resulting in the cure of his skin affliction or blood disease.

Bathhouses and hotels sprang up, and by the early 1900s, Marlin was a hot spot for spring training among professional baseball clubs, including the Chicago White Sox, Philadelphia Athletics, and New York Giants. “Drink it. Best stuff on earth,” a practice field groundskeeper urged a New York journalist when he saw the scribbler frown at the water’s taste, according to a 1908 Democrat story. As late as 1956, the American Society of Medical Hydrology held its annual meeting in Marlin.

“Marlin’s mineral water was utilized as a therapeutic tool into the 1960s,” says Janet Abbott, an Austin resident and president of the Balneology Association of North America, which researches and promotes mineral waters for wellbeing. “Modern medicine directed seekers away from the water cures by replacing natural treatments that took time and patience with heavily advertised, quick-fix pharmaceutical remedies.”

Today, Marlin’s hot sulfur water still flows from a fountain at the town’s chamber of commerce, and people can still fill jugs for free.

“Modern medicine directed seekers away from the water cures by replacing natural treatments with … pharmaceutical remedies.”

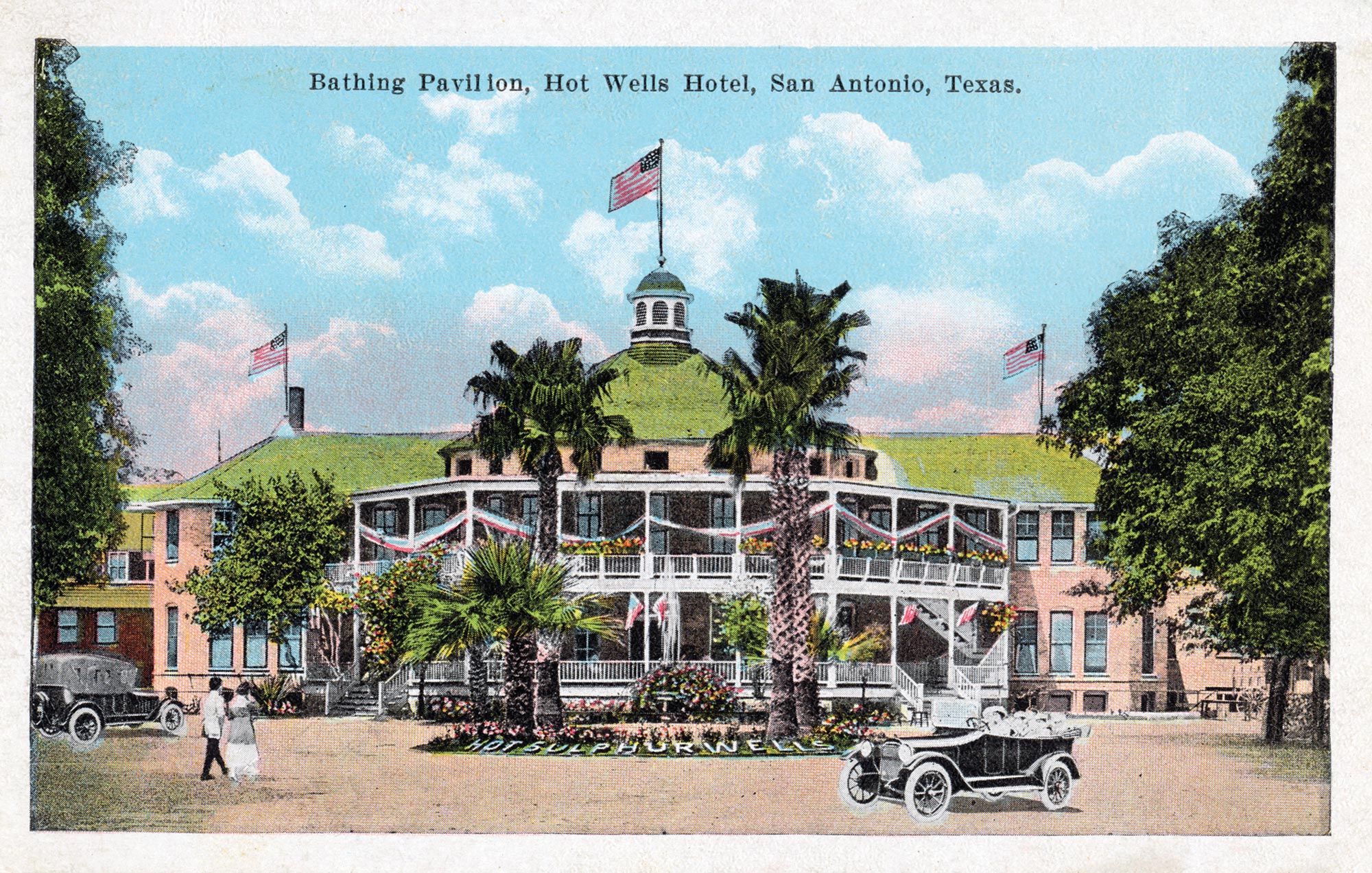

The same year that Marlin struck its water gusher, 1892, San Antonio drillers uncorked a fountain of hot mineral water on the grounds of the Southwestern Lunatic Asylum, across the San Antonio River from Mission San José. Leased to a succession of entrepreneurs who built elegant hotels and bathhouses, the site—dubbed Hot Wells—attracted not only health-seekers but also celebrities such as Will Rogers, Theodore Roosevelt, and Porfirio Díaz. “No use to go outside the state to Topo Chico, Mexico, or Hot Springs, Arkansas,” promised a Hot Wells advertisement in San Antonio’s 1892-93 city directory, “as these springs are not only equal, but superior to them.”

Hot Wells visitors could also enjoy dancing, bowling, gambling, visits to Mission San José, and the spa’s alligator and ostrich farms. In 1910 and 1911, spa guests could venture across the river to watch French cinema pioneer Gaston Méliès make silent films. Shooting feverishly, Méliès’ Star Film Ranch made some 70 movies in San Antonio, including The Immortal Alamo. Today the company’s 20-acre site is part of Bexar County’s Padre Park.

Movie magic also graced the state’s largest and best-known spa, Mineral Wells, tucked in a picturesque valley of the Palo Pinto hills in North Texas. With its two grand hotels, the Baker Hotel and the Crazy Hotel, both built in the late 1920s, silver screen legends like Clark Gable, Marlene Dietrich, and D. W. Griffith visited the “town built on water.”

The James Lynch family discovered the healing waters of Mineral Wells when they drilled a well in 1880. The resource tasted funny, but after drinking it for a while, family members felt renewed and restored. Soon, locals were crediting the water with curing everything from cancer to anxiety and rheumatism.

The next year, a woman suffering from dementia sat drinking from one local well for days on end until, as town legend tells, “the crazy old lady was not so crazy anymore.” In time, the well became known as the “Crazy Well” and Crazy Water became Mineral Wells’ best-known brand. The fact that it contains traces of lithium, an element used to treat mental imbalances, may indicate some fact among the folklore.

Crazy Water is bottled in Mineral Wells.

Photo: Michael Amador

The Great Depression of the 1930s slowed the number of customers trekking to Mineral Wells to “drink their way to health.” But economic hardship was only one factor that spelled the gradual decline in the popularity of mineral-water resorts in the 20th century. The discovery of antibiotics and other medical developments also took a toll, along with the advent of television and changing social trends.

It’s hard to beat a natural elixir like Crazy Water, though, bottled today in the Brazos Valley spot where it was discovered. Indeed, the hydration and health appeal of mineral water remains evident in the variety of bottled offerings that fill the shelves of grocery and convenience stores. As they say in Mineral Wells, “Crazy Water—making people feel good inside and out since 1881.”

Taking the Waters Today: Not Such a Crazy Idea

While mineral-water resorts have gone the way of the foxtrot and the interurban railroad in Texas, for those who seek, the water still flows. Crazy Water from Mineral Wells is available at grocery stores, but nothing beats a pilgrimage to the antique Famous Water pavilion in Mineral Wells to taste the Crazy beverage at its source.

Famous Water Co., which sells Crazy Water, recently restored the Crazy bottling plant and opened a Crazy Bath House, where guests can bathe in the waters and spend the night. Both of the town’s grand hotels, the Baker and the Crazy, are closed. Local investors are in the early stages of restoring the Crazy Hotel as a mixed-use development, while renovation plans come and go for the Baker.

In San Antonio, Bexar County is stabilizing the Hot Wells ruins as a park projected to open this year, while the nonprofit Hot Wells Conservancy plans to establish a museum and visitors center. Though the site’s well has been plugged, developer James Lifshutz, who donated the site to Bexar County, plans to drill a new well on adjacent land and offer therapeutic bathing. “People all over the world are drawn to thermal healing waters,” Lifshutz says, “and I want to bring back that legacy.”

You can also take a hot mineral bath right now out at Chinati Hot Springs in Ruidosa, near the Texas-Mexico border southwest of Marfa.