Clearly I am not the only one who yearns to bring a bit of Spain back to Texas. For the first half of my 30s, I lived in Madrid less than 600 meters from the Museo Prado, the holy ground of Spanish art that holds within its hallowed walls the masterpieces of Velázquez, Goya, and El Greco. These treasures of light, shadow, allegory, and humor became a regular part of my Madrid life.

The Meadows Museum is on the campus of Southern Methodist University, at 5900 Bishop Blvd. in Dallas. Call 214/768-2516

It would seem that the late Algur Meadows, the CEO of Dallas-based General American Oil Company, fell into a similar rhythm when he frequented Madrid in the 1950s searching for Spanish oil. The oil never materialized, but something more precious did—a passion for Spanish art. He, too, would walk over to the Prado on a regular basis, and he fell in love with what he found there. But while I brought back a mere refrigerator magnet of one of Velázquez’s paintings, Meadows brought back actual Velázquezes.

He eventually amassed such an impressive Spanish art collection that in 1965, in honor of his late wife, Virginia, he founded the Meadows Museum on the campus of Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Nicknamed “The Prado on the Prairie,” the Meadows Museum is considered one of the finest Spanish art collections outside of Spain.

In a magical few hours spent exploring the Meadows recently, I gazed intently not only at paintings by the Spanish masters, but also at works by contemporary Spanish artists I recognized from ambles through Madrid’s modern art galleries. I marveled at the museum’s wildly playful paintings by Joan Miró, which Miró himself had selected for Mr. Meadows; the artist and the collector had become friends during Meadows’ many visits to Spain.

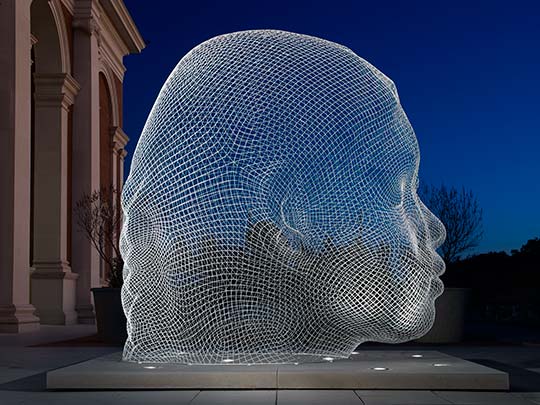

Because Meadows’ second wife, Elizabeth, loved sculpture, the museum has a small 20th-Century collection by non-Spanish artists such as Claes Oldenburg, Isamu Noguchi, and Henry Moore, which enlivens the outdoors plaza. Nearby are more works from Spain, including Sho, a transparent 13-foot head by Jaume Plensa, and The Wave, a 40-by-90-foot kinetic sculpture by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, which ripples continuously on the museum’s lawn. The manicured and quiet SMU campus feels a world away, both geographically and energetically, from the busy streets of Madrid, but when I hear The Wave creaking, I feel closer to Spain.

But the lecture that day practically transported me there. Presented by the museum’s director, Mark A. Roglán, a former Madrileño who was knighted by King Juan Carlos for his “contributions to Spanish art in the world,” it opened my eyes to Spanish art I’d known nothing about. I hung onto every syllable of Roglán’s Spanish-accented English as he connected the dots between the Golden Age of the 15th and 16th centuries and early 20th-Century Spanish art.

Reluctantly, I made myself leave the lecture early to catch the last half of a guided tour of the Meadows’ current temporary exhibition, Goya: A Lifetime of Graphic Invention (on view through March 1). The exhibition focuses on Goya’s four major print series, created between 1799 and 1823—including Los Caprichos and Los Desastres de la Guerra, copies of which I had first seen in the underground metro station near Madrid’s Retiro Park. I’d never paid much attention to the prints, though, preferring Goya’s gorgeous paintings. But here I was, amazed, hearing about how he was a ceaseless experimenter, always seeking new forms of expression. Goya had achieved stature by painting for the Spanish royals for 40 years, but he always maintained his sense of exploration, social satire, and independence. Until his death, Goya was still testing out new printmaking methods and pushing the limits of what had been done before.

Standing in the upstairs gallery space at the end of my afternoon at the Meadows, it dawned on me that I could follow his example. Watching as the setting sun cast circles of pink and orange around the Jaume Plensa sculpture outside, I vowed to try to be more like Goya, curious and open to learning more, despite changing circumstances, nostalgia be damned.

Seeking a reminder of my new Goya-inspired manifesto, I popped into the museum shop. The magnet selection was slim. I picked out the only Goya magnet they had, a heart-wrenching and powerful painting owned by the Meadows titled Yard with Madmen. It was a painting I’d never heard of before, and, while grim, it was a reminder of Goya’s lifelong exploration. It hangs side by side now with my Velázquez magnet, and every time I open the fridge, I am reminded that Spain, Goya, and new discoveries are closer than I think.