For two days, we traded places on the road with the polygamists’ trucks and an accompanying big, white van. Though in many ways nondescript, designed not to attract attention, I knew—all were filled with children, all had up-to-date Arizona plates. I relayed stories to my boyfriend of growing up in Salt Lake City with a polygamist nanny, getting haircuts and massages from her sisters, and wandering the secret passageways of Warren Jeffs’ abandoned fundamentalist compound at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon.

A few times, we filled up at the same gas station as the caravan. I’d sit on the sizzling hood of Dad’s Lexus and take in the sister wives with their tight braids and wish I had a cigarette, wish I smoked, so I could blow mysteriously in their direction.

On the homestretch into Austin our final night on the road, we cruised through Round Rock and the blinking yellow lights of Pflugerville like we were making a getaway. We could have been hauling butt to Mexico even though we knew we’d only make it as far as a Motel 6 on the side of Interstate 35.

Bleary the next morning, I pulled the Lexus onto the frontage road too slowly. A car came up behind me and tapped my bumper, knocking me out of yesterday’s reverie and putting me squarely back in the driver’s seat of my dad’s car. The guy who rear-ended me was funny and sweet and flirted with me right in front of my boyfriend. We didn’t even exchange information. It was my first day as a Texas resident, and I remember thinking I liked it here already.

My dad bought the Lexus when I was first learning to drive. Picture that silver submarine of a luxury sedan as I first saw it, glittering under the showroom lights at a dealership in Salt Lake. A dream car for a certain kind of middle-aged man, the LS 430 had a creamy white leather interior, glossy wood paneling, and softly lit mirrors that somehow made my acne less terrifying.

My dad owned newspapers in small towns in Utah, southern Idaho, and Washington. The idea behind buying the Lexus was to travel to them in comfort, listening to James Taylor and tracking his progress on the car’s novel GPS system, an arrow always pointing him in the right direction. He could even have the map talk to him or record a two-minute voice memo in the den-like hush of the car’s interior. He named the car what he’d always wanted to name me: Rex.

I was born with mild cerebral palsy, and my bum right leg and terrible sense of direction rendered me an adequate student driver at best. Normally easygoing, Dad confirmed the suspicion of my shaky skills by being too nervous to teach me. At his urging, the summer before I turned 16, I enrolled in a private driving academy in the basement of a hair salon and signed up for driver’s ed through my high school in the fall. I needed all the practice I could get. “From professionals,” Dad said.

The few times I went driving with Dad in Rex, he let me experiment first with using one foot for each pedal and then just my strong left foot for both. It turned out I was better off depending on my flimsy right foot after all, even if I had to lift it completely off the accelerator and move it to the brake, occasionally sending it smashing down. “You should team up with a bank robber,” Dad said, clutching the bar above the door. “You’ve got a heavy enough foot for it.”

The joke ended up being on Dad. The fall of my senior year of college, he was diagnosed with ALS. The shoe was now on the other foot, and it was so much worse. Dad was the scary one on the road. I had to learn to be patient with him in the way he’d had to be patient with me. I’d lift his weak arms onto the wheel and turn the key in the ignition while he pressed the brake, and then I’d shift the car into gear. He steered mostly with his wrists and thighs, but I still admired how his foot danced between the pedals more gracefully than mine ever could.

Dad’s ALS progressed rapidly, and he soon lost the ability to drive entirely. I went from being a getaway driver to an incompetent chauffeur, ferrying Dad to his office, or to our support group, or to his respiratory clinic as he prepared to get a tracheotomy. His diaphragm wasn’t hacking it.

Once Dad was permanently hooked up to a breathing machine, and largely stuck in bed, I took over Rex. The fancy car I’d once been terrified to drive to prom now brimmed with leftover bowls of oatmeal and green smoothies I’d blended on my way out the door. I started racking up speeding tickets and lackadaisically locking the keys in the car. Once, when the battery died, I tried to jump Rex but hooked the cables up in the wrong place. Sparks flew and the sleek V8 engine almost caught fire.

“It’s good Greg is in a super safe car,” my brother Danny offered. “That way, when he gets into an accident he probably won’t die.”

Before Dad got sick, he was our family’s fleet manager. Our cars were always operating at maximum efficiency under his supervision. He made sure our tanks were full and our oil changed. He’d even squeegee my windshield, like a gas station attendant from the olden days. Without his roadside assistance, I quickly discovered the difference between borrowing your dad’s Lexus and being responsible for it: money. Replacing an opulent LED headlight cost hundreds of dollars; replacing a sideview mirror I’d knocked off was also a small fortune.

A year into my involuntary takeover of Rex, Dad was in bad shape. Since getting a tracheotomy, breathing was no longer a struggle. But ALS had wasted away the muscles in his chest and shoulders, made quick work of his hands, arms, and legs. Only his mind was still intact.

Dad and I talked all the time about how much longer he wanted to keep going. Initially, he had said he’d die when he could no longer talk. Later, he set a date for the first day of fall, his favorite time of year. He pulled the plug three weeks before my 24th birthday.

Of the many fine things I inherited from my dad—his old Asics and teeny-weeny running shorts among them—Rex was my least favorite. It was more of a responsibility than a perk. When I thought about Rex, it was with an air of grievance. Anytime I turned him on, the car’s seat and mirrors automatically readjusted to my dad’s preset specifications. Since my dad was two inches taller than me, I was left with the nagging sense that as long as I piloted his car, I would fail to measure up. No matter how many surgeries I had on my hamstrings and Achilles tendons, I could never be stretched into the man he’d been.

Perhaps enacting a cliché about grief, I quit my job as the arts editor of a newspaper in Utah and moved to Los Angeles to try to make it as a screenwriter. I applied to MFA writing programs on the side, and several months of unemployment later, I got a fortuitous call from the director of the Michener Center for Writers. The ghost of James Michener—titanic historical-fiction novelist, late-in-life Texan, and, most relevant for our purposes here, childless orphan who endowed millions to the creative writing program at the University of Texas at Austin—was shaking a tree of money over my head in the form of a three-year, fully funded fellowship to write fiction.

Hardly an adventurer like Michener, I nevertheless craved what he might call the grand enterprise coursing through me on the open road that summer. I felt like I’d carjacked my dad’s dreams and was now enacting the midlife crisis that was rightfully his, peeling away from responsibilities, horns honking in my wake. I couldn’t have been happier. I wanted to live in a state that wrote bigness into its motto and promised a happy retirement for Rex, his rusted undercarriage and many dents reminders of salty roads traveled and smoother ones ahead.

One thing I loved about Austin from the start is its habit of casting its favorite sons and daughters in bronze, from the endearingly flabby interlocutors of Philosophers’ Rock outside Barton Springs to guitar colossus Stevie Ray Vaughan on the shores of Lady Bird Lake. You’d be forgiven for expecting to find a statue of James Michener in the city, but the only monument to him I’ve found is an unfussy headstone in Austin Memorial Park. Michener’s ashes are buried beside his wife Mari’s in the shade of a live oak next to MoPac. It’s not an unpleasant spot—there’s a wind chime in the tree—but it is an inconspicuous one. If Michener has left any monument behind, it’s the writing program that bears his name and the writers who have moved through it. “Daddy Michener,” we called him, fondly and a little teasingly, when his checks hit our accounts each month. The Michener days were some of the best of my life. They gave me a shot at becoming who I needed to be. I could write ghost stories and silly screenplays all day and then drive to a friend’s house in Windsor Park to get drunk and make up country songs. An artist is only as good as his patrons, and I had two: Saints Michener and Rex.

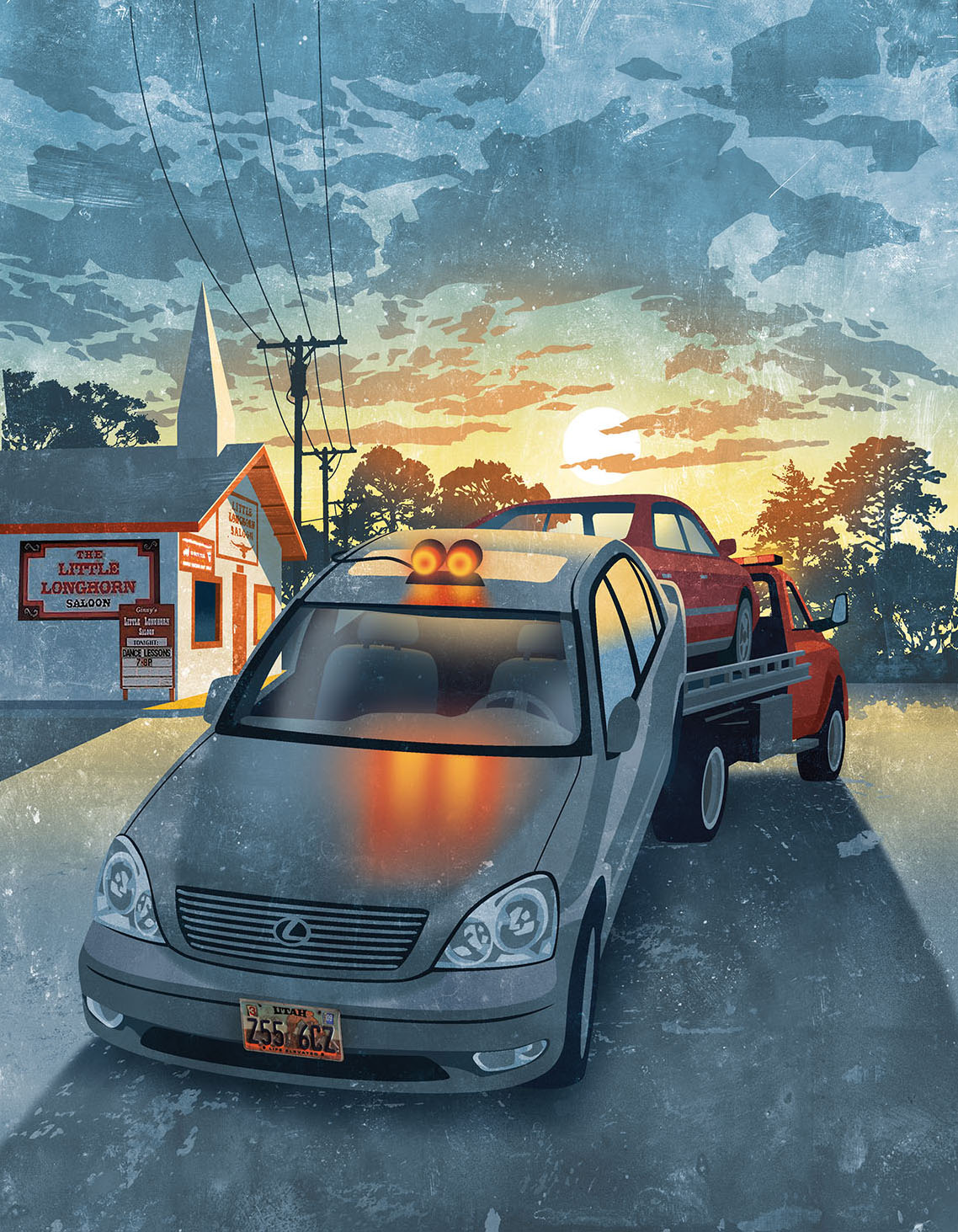

Rex’s health stabilized a bit once he only had to take me to coffee shops and bars around town, or on dates to Schlitterbahn and Hamilton Pool with the new guy I was seeing, Lucas. My grand enterprise wasn’t going from place to place, though. It was finding parking. The Austin I tooled around in more than a dozen years ago was a town of crowded parking lots; the age of the parking structure was just dawning. Compact spaces had caught on, but compact cars hadn’t. Rex was as cumbersome as a boat. I could usually get a spot at Randy Palmer’s South Austin Gym on South Lamar, where I rode a squeaky old elliptical, but it was always one of the last spots. Same with Chicken Shit Bingo, where I emerged from Ginny’s Little Longhorn Saloon one Sunday afternoon to find Rex boxed in by a pack of motorcycles.

Even living as a snowbird, Rex was only so dependable. His bulky majesty far outstripped my world-class graduate school stipend. The back end needed new shocks, and the trunk would come crashing down hard enough to lop off fingers when I unloaded groceries. The tailpipe rattled and smoked. I never knew when the Lexus would crap out or fail an emissions test or blow a tire or a gasket and need to be towed down the street to my mechanic, Don. He would invariably tell me, from his ozone-scented office decorated with roller derby trophies and calendars from the local teams he sponsored, I needed not just a mechanic but also a body shop.

Though I was driving Rex, my mom remained the car’s legal owner and paid the insurance. Thus, the Lexus retained its flaking Utah license plates, which featured an increasingly sooty Delicate Arch covered with crooked registration stickers I applied for remotely, citing a student exemption. I kept my Utah driver’s license, too, immortalizing the faux hawk I’d worn that day at the DMV. Inadvertently, I’d labeled myself not a Texan but a Utahn living abroad.

Doormen at bars would check my ID and mutter derisively about Mormons. I was asked all the time if I belonged to the church. I could see people taking in my dark blond hair and blue eyes, the kink in the way I stood, and telling themselves a story about me, one that may have involved excommunication, abuse, escape. I may not have been an FLDS lost boy, kicked out of a church that, by the dictates of plural marriage, requires more girls than boys, but I looked the part. If you asked a stranger, I was the polygamist now.

As the years passed, I kept putting off getting rid of Rex. At first, I said I wanted to make it to the end of my time at the Michener Center before getting a new car. Then it was after I got engaged to Lucas. Then it was after the wedding. All the while, the car’s damage mounted. Never fixed right in the first place, a finicky headlight died for good and began gathering condensation. The starter was on the fritz, too. To get Rex to tremble to life, I had to turn the ignition twice and hold it there like a knife to the throat. There was also something electrical going on, or more likely, many things. The doors would lock and unlock on their own. The dashboard frequently went into disco mode, flickering off and on.

“My dad, the partying poltergeist,” I’d tell Lucas.

Don the mechanic finally told me it was time to cut my losses with Rex. It was silly to feel fondness for an old car. My dad was not the sort of person to get attached to things. I wouldn’t be either.

To my surprise, when I tried to find a buyer, I came up empty. It was like the car didn’t want to be sold. A Lexus that had once attracted under-the-table offers from Jiffy Lube employees looking to lowball a disabled 30-something out of his dad’s sweet ride now received catcalls at red lights. The car was barely worth the dollar I’d offered Mom to transfer the title. Texans are wary of salt damage, Don explained, and Rex had plenty of it.

“If you really love your dad’s car, maybe you should stop crashing into things,” Lucas suggested. “You could even run a vacuum through it.”

“Dad gave Rex to me,” I told him. “Neglecting him is my birthright.”

And that’s what I did, right to the end.

In the fall of 2017, when Rex was no longer drivable, I bought a used Fit from Howdy Honda and pulled the Lexus permanently into a guest spot in our condo’s parking lot, where fallen leaves would pile up on the windshield. Seeing me limp away from the car, a neighbor asked, “Were you in an accident? Do you need me to call someone?” At first, I blew her off, finding myself irritated with my dad even though he’d been dead for nearly a decade. “It’s my dad’s car,” I said, like that explained anything.

It wasn’t until Rex’s Utah registration finally lapsed, at the end of that November, that I got desperate and started answering ads reading Scrap your car for charity and We haul away junk cars.

Junk. I’d turned my dad’s dream car into junk.

You could say I was a coddled slob who didn’t deserve nice things, and you wouldn’t be wrong. But it’d be more accurate to call me an emotional hoarder in a state of arrested development. Rex wasn’t junk. He was a time capsule for all the memories I’d made without Dad, all the things I still wanted to show him. A bumper sticker I’d acquired on day one in Austin feebly clung to the dent on the rear bumper. Coins were glued in cup holders, adhered by some unidentifiable substance. The leather seats were as sticky as flypaper. Two hubcaps had gone missing, tires stripped to the studs. The sole of my tennis shoe had streaked the inside of the driver’s side door where I swung in my leg. My habit of sitting hunched left an imprint on the car, too: The spot on the console where I rested my elbow was worn down to dirty foam.

It was nearly Christmas by the time I found someone to haul away Rex—as in, unscrew those Utah plates and auction off his parts for charity. Rex didn’t need a mechanic or a body shop. He needed a coroner. Fred was an expert at intake for cars, trucks, and boats—or so the pink font on his website claimed. Accepting the title to the Lexus with a very Austin “Thanks, hombre,” he put two flashing red lights on top of the car and hoisted its rear end onto his truck. Tipped on front wheels, Rex’s bruised grill smiled wearily at the ground, ready for a final commute.

A dying car is like a dead dad: a total pain. I couldn’t ditch either fast enough. But in time I found my grip tightening over the scratched James Taylor CD that spun in the changer for nearly two decades. It didn’t matter how many dings I put in the Lexus, how many parts I replaced or state lines I crossed. None of it changed one simple fact: Rex was his car, never mine. Dad was always along for the ride as long as the ride was his 2001 Lexus LS 430. Now, I would have to make my way without him. Not every titan gets cast in bronze.

In the long shadows and white light of that winter morning, I watched the tow truck, then Rex, bounce over our condo complex’s yellow speed bump, crest the hill at the top of the driveway, and slowly turn out of sight into traffic. I stood at the bottom of the driveway and wept.