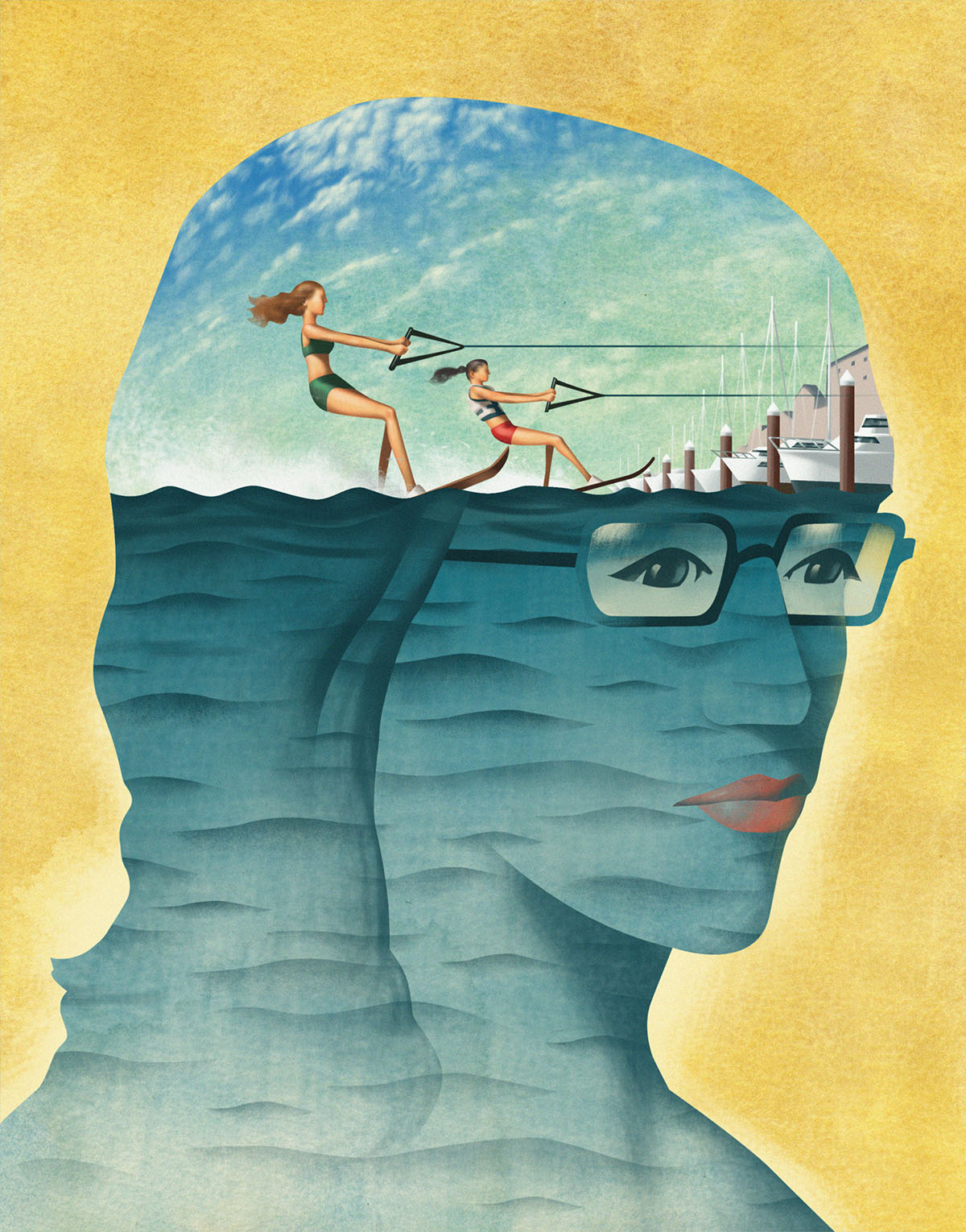

Slaloming to Freedom

On Lake Sam Rayburn, a mother teaches her daughter how to persevere

By Suzy Spencer

I don’t have to close my eyes to go there in my mind.

I didn’t close them when I was sitting in the second row of my grandmother’s funeral while my mind’s eye watched the summer breeze ripple the surface of Lake Sam Rayburn, my lime-green O’Brien slalom ski slapping against the water.

I felt the tug on my arms and my shoulders as I leaned hard right to cut outside the wake, my ski and I becoming one. We lifted above the water as we jumped. I heard the clap as we landed again on the surface. I cut left and felt Rayburn razoring against my ankles. I zoomed back over the wake and watched our boat’s spray rainbow over my head. I jumped the second wake, cut again, watched the spray, cut back, again and again until my arms and legs throbbed from the tension. But I couldn’t stop skiing. If I did, I’d cry, and I didn’t want to cry at my grandmother’s funeral.

So, I leaned in and cut harder, faster, deeper into the water, listening as my ski slapped harder, louder, until I cut so sharply that my spent arms, legs, and shoulders gave out, forcing me and my ski to slip. My right hip hit so hard against the water that my O’Brien and I separated. I somersaulted—one, two, three, maybe four times or more—deep into the lake, so deep that I didn’t know where I was, which way was up, until I reminded myself to look for the sun.

Then I saw it—its rays shining through the brackish water. I swam toward the light. I popped the surface, looked for my ski, spotted it, swam to it, held it perpendicular to the sky, like a loblolly pine towering against the blue, and waited.

I waited, until I could go home again.

Nearly 45 years later, I still yearn for that home and long to relive those memories of love, freedom, and joy. Last fall, I returned to where I first dipped my toes into the lake at Hanks Creek, just a 15-minute drive on US 69 from my hometown of Lufkin to my mother’s hometown of Huntington, followed by a winding 20-minute drive on Farm-to-Market Road 2109 to Farm-to-Market Road 2801. Known as Hanks Creek Marina back in the 1970s, it’s where my family—my mother, sister, and aunt—put in our gray and yellow Evinrude, the boat that preceded the blue and white one.

With the boat tied to the end of the dock—packed with a cooler full of Coca-Cola, a bucket of minnows, cartons of worms, fishing gear, and my Cypress Gardens Mustang water skis—we burned beneath the East Texas sun while we waited for my uncle to drive up in his air-conditioned Lincoln Continental. He’d park his car among the pickup trucks and empty boat trailers, still dripping water from putting in their boats, and stroll down to the ramp carrying only his tackle box as though it were his medical bag. He’d grin, jump in the boat, and say, “What took you so long?” Then he’d power up the engine like he was the captain of a luxury yacht.

He and the rest of my family only wanted to fish, while I begged and pleaded to ski. Finally, to shut me up, my uncle would toss my skis and me in the water. I’d slip my feet into the gray boots, grab the single-handle ski rope, watch my wooden skis knock together as the boat slowly pulled the rope taut, and pray that I could get up.

That’s what I pictured as I drove through the Piney Woods last year. I was eager to return to the parking lot that was always packed, ready to walk out on the marina and listen to boats in their slips, their ropes squeaking with every wave, the sound of smooth engines at their slowest revolution as they eased through the no-wake zone.

Then I realized that every sign I passed said “Hanks Creek Park,” not “Hanks Creek Marina.” Was it gone?

I was probably 13 when I first came to Hanks Creek, and I didn’t have the stamina to ski for long. After a few minutes, I’d fall from exhaustion, my body sinking into the water, and also my joy because I knew that one fall meant my family would go back to fishing.

Now I stand in an empty Hanks Creek parking lot. The wind rustles the trees, birds sing, water splashes softly against the shore. I can breathe for what seems like the first time in years. I am home.

There’s no marina anymore, but there’s a dock, a worn basketball court, the skeleton of a volleyball court, a play area for kids, campsites, and a woman, Medina Sharp, who was contracted to pick up litter in the park.

Medina tells me Hanks Creek started changing in the mid-1980s. The local rumor is that the marina’s owners’ bank note went south, the bank foreclosed on them, and one of the owners poisoned the marina’s well system out of plain old meanness. But, again, that’s only a rumor.

“That’s when the Corps really got involved,” he says.

In fact, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers first became involved in 1956, when construction began on a dam across the Angelina River—a dam that had been authorized by Congress in 1945 to help flood control, create hydroelectric power, and provide water for municipal, industrial, agricultural, and recreational uses. When the lake filled up in 1968, Sam Rayburn Reservoir covered 114,500 surface acres and became the largest lake completely inside of Texas. Today, 22 parks and private concessions dot the lake’s 750-mile shoreline. Some of those are operated by surrounding counties, some by the U.S. Forest Service, and 10 of them, including Hanks Creek, are operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

According to Medina, the Corps spent several years cleaning up the Hanks Creek wells. The Corps also improved the boat ramp, restrooms, and bathhouses; built a picnic pavilion, 47 designated campsites, and eight screened-in shelters with tin roofs; and, as Russell describes, “turned this into an actual park where you make reservations.” He points toward the woods. “There was a road that went way back in there and came out to a place called Sandy Beach. That’s where everybody used to go and drink beer and get pretty wild.”

That was back in the days when you could find any old camping site you like, he says, chain a chair to a tree on the site, leave, come back a few hours later and still have your spot.

Like me, Russell seems nostalgic for the Hanks Creek of the past, but he’s not. “This is a good family park,” he says. The Corps shut down Sandy Beach and the beer parties long ago; now kids can ride their bicycles and no one’s going to bother them. “This really truly is a jewel in East Texas,” he says, “and I’ve been to every park here. This is the best.”

“Why?”

“It has more waterfront camping spots than other sites,” he says.

I glance over at one of the tiny, screened-in cabins, its tin roof covered in dry pine needles. I want to open the cabin’s shutters, lean my slalom ski in a corner, set up a cot on the concrete floor, and lie there—after a hard day of skiing—listening to rain on the metal roof. Or maybe sit outside on the front porch, wieners roasting over the fire pit, watching fireflies flutter between the pines.

“And the fishing is great,” Russell adds.

“Do people still water ski much?”

“Not like it used to be.”

There’s a 10-foot alligator living on campsite No. 37, as well as a bunch of four- and five-footers. But there are also eagles, which can be seen from campsite No. 26. “They’ll swoop down, they’ll pick up a fish, and then they’ll go sit in a tree,” Russell says.

I’m starting to like this Hanks Creek. But since I don’t have a cot and will always prefer skiing over fishing, I steer my car toward Zavalla, where I get on State Highway 147 North, cross over Sam Rayburn, and take a left on Farm-to-Market Road 2851 to Jackson Hill Marina.

Jackson Hill was where I used to pop a stick of Trident cinnamon gum in my mouth, jump in the lake in my red ski vest, grab the tow rope, pull on my slalom, and yell, “Go!” The water here was broad and the tree stumps were few. As I sliced across the wake, I chomped my gum with the rhythm of my ski. The wind roared in my ears and I screamed, believing no one but God could hear my joy.

This is where my friends and I floated after skiing, slowly paddling in the warm water, searching for a cool spot where the river once ran. It’s where we ate Tinsley’s fried chicken, tossing the bones overboard, watching the grease cast pink and blue rings, and listening to the fish pop the surface as they lifted their lips to the food. It’s where we filled our empty Coke cans with Rayburn and poured the liquid on the deck to cool our burning soles.

Now I stand on its bank, beneath trees hanging heavy with Spanish moss, staring at a heron trying to hide along the shore, and watching a lone fisherman sitting in his bass boat. I’m starving and quickly learn that Jackson Hill Lodge is the place to go if you want to taste a savory pulled pork sandwich and talk about bass fishing.

“There are around 400 organized bass tournaments on Rayburn every year,” owner and chef Terry Sympson says. “It’s the most in the United States. Around the country, if you talk to a bass fisherman and you say ‘Rayburn,’ they either say, ‘Yeah, it’s my favorite lake to fish,’ or they’ll say, ‘It’s on my bucket list.’”

But I want to know if people still water ski here. Even on the busiest summer weekends, Terry says, there are only a couple of skiers and wakeboarders. “It’s the best kept secret,” he says and shushes me not to tell anyone.

I look through the lodge’s window and out to the water. In my mind, I see my smiling friends, who, like me, only wanted to ski. Go!

I couldn’t slalom back then, but I was determined to learn. Thankfully, my friend Paula, who was renowned as one of the best skiers on Rayburn, was just as determined to teach me.

She and I jumped in the water as my mother maneuvered the boat and Paula’s mother settled in as our spotter. Paula strapped on my old Mustangs so she could ski beside me as I attempted and attempted again, then failed and failed again, to slalom. But Paula and I weren’t quitters. With her coaching, I learned and became almost as good of a skier as she.

Now I stand on an empty slab at Shirley Creek, my memories feeling like ashes to be scattered from their urn because this empty slab was once a restaurant with the best hamburgers around. I want to be eating dinner here with Paula and our mothers. I want to hear the sizzling of the meat on the grill and taste the juices in my mouth. I want to hear our laughter, mingling with that of the other skiers.

But just like Hanks Creek and Jackson Hill, Shirley Creek is mostly people fishing and camping. Where ski boats once parked, there are RVs and a few log cabins. I don’t recall either being here when my mother allowed me to take my friends out on the boat, me walking down the gangway carrying my O’Brien ski case stuffed with my ski and gloves, my ski vest looped around my arm.

I miss the sound of the puttering engine as I backed out of our slot. I miss the smell of the water flecked with specks of tree bark. I wish I could stop longing without forgetting.

I walk down to the swim beach—it, too, didn’t exist when I used to come here—and try to make new memories. I study the angle of a bass boat in the water, the tilt of fishing nets leaning against the port side. I notice a seemingly abandoned rowboat as lilies float in the water and herons glide just above its surface. The light shimmers gold on oak leaves while egrets try to hide beneath cypress. I admire the stark beauty of trees sheared bare from tornadoes. Suddenly, storm clouds move in, turning the water from blue to green and then gray. I retreat to my log cabin as I feel sprinkles on my skin, stopping only long enough to notice the RVs, some with porches and fences, many with golf carts and satellite dishes, almost all with boats. This is a community, but I don’t want community.

I seek solace, and the lake-view log cabin I have rented for the night is a writer’s retreat. There are a couple of chairs on a front porch, an easy chair inside, a TV that gets sporadic reception so as not to distract, a kitchenette, a clean bathroom, and a dark bedroom where I am tempted to lie down and listen to the pitter-patter of rain on the metal roof. But it’s too early for sleep and the rain soon ends, so I scurry down an embankment to the lake. This is an area of Shirley Creek that I never knew existed. A tree cove to my right calls me to explore it.

In this hillside cove, I discover an opening, fenced with pine and curtained by oak heavy with moss. Mysteries permeate that moss, the bark, the pine needles, even the weeds and dirt. Part of me wants to run from their secrets, but more of me wants to set up a wooden desk and chair, open my laptop, and listen to the stories lurking in these woods.

The sun begins to set. Clouds blow in heavy and dark. I spent so many teenage summer afternoons in Lufkin watching the clouds, wondering if they were going to build into thunderstorms that would prevent my mother from taking Paula and me skiing. But I’ve never seen anything like I’m watching now—a roiling sky of yellow, tangerine, peach, gold, cobalt blue, and smoke grey.

As I watch, I can see in my mind Paula and me slaloming through the cut from Shirley Creek to Hanks Creek, heading toward Jackson Hill. We’re almost to Hanks when the boat stops. I raise my thumb to my mother, signaling her to shove the throttle forward. She doesn’t. Paula and I begin to sink. “Go! Go!” I yell.

Swells start to swamp us. White caps wash Paula and me away from the boat. Mom tries to circle back to us. The wind pushes the boat past us. I try to swim and can’t with my ski. Slowly, my mom maneuvers the boat closer to us, stretches out her arm, and pulls me in. Paula scrambles up behind me.

The unforeseen storm had blown our boat to a stop.

Another unforeseen storm blew our boat to a stop a few days after my return from Rayburn. My mother had a series of strokes. She can no longer walk. She can’t feed herself. She can barely talk. But I lean down to her ear and say, “Did you like fishing at Rayburn?” She grins big and mutters, “Oh, yes. I loved it.”

I feel myself finally, reluctantly, letting go of my tow rope and sinking into the water.

“But did you like taking Paula and me skiing?”

My mother smiles even bigger and says, “I loved it.”

And with that I know that when she passes, I won’t have to close my eyes to see her in our ski boat, reaching out, pulling me in, safe and secure.

We’ll both be home.