Feel Right at Home

A sixth-generation Texan returns to a beloved landscape to endear her husband to her home state

by Dina Gachman

My mom always said an anthill in Houston may as well be a mountain. She longed for majestic landscapes found on postcards of the California coast or the French countryside. Instead, she spent all 68 years of her life surrounded by the comparatively flat terrain of Fort Worth and Houston. She complained, but she never left. She was surrounded by anthills instead of Alps, but Texas was her home.

Unlike my mom, I did eventually leave Texas in search of grander vistas. I followed the well-worn path to California, the one so many before and since have traveled. Once there, I was sure I would never leave. Humidity was generally low, city streets smelled like jasmine, and bursts of magenta bougainvillea seemed to bloom year-round. I figured I’d be one of those Texan expats who appreciated home more deeply from afar. The kind who lifelong residents probably want to toss off the side of a steep cliff for our traitorous ways.

Funny thing is, my long-ago dream of living and dying in California—with a brief stint in Paris, naturally—seems lonely to me now. Instead of spending my days lounging in a French café, I’m a mom living in Round Rock, a once sleepy suburb north of Austin that’s now luring an alarming number of transplants from California and New York. The most Parisian thing I’ve seen near my house is a French bistro in Pflugerville that sells crepes, quiche, and croque-monsieur. They also sell Dr Pepper, of course.

Now I live near Brushy Creek instead of the Seine or the Pacific, and I’m not the first to make that sharp midlife turn from the city to the suburbs. Several years before I U-turned back to Texas, I fell in love. I got married and had a child. Suddenly, my dreams and ideals weren’t the only ones that mattered. I had to navigate those roads with my husband.

I met Jerett in Los Angeles, the city we’d each adopted as our own. I moved there at 18 for college; he came out for a job after medical school on the snowy East Coast, mainly because he realized Los Angeles had beach days in February. He grew up in a small Massachusetts town called Seekonk, surrounded by blueberry farms, luxuriant purple hydrangeas, and towering pines. Because of this, he shares my mom’s love of lush vistas. Unlike my mom, though, my husband doesn’t have Texas roots stretching back five generations to deepen his appreciation of our rugged terrain. He has zero nostalgia for a childhood spent eating little cups of Blue Bell with wooden spoons or riding glass-bottom boats at the defunct Aquarena Springs in San Marcos. His only real tie to Texas, a place he never imagined he’d call home, is me.

In 2014, I brought Jerett to visit Texas for the first time, after we’d been dating close to a year. We flew in from Los Angeles, and after meeting up with my parents at their Houston home, we headed west on Interstate 10 about four hours to a rented house in Concan. Jerett and I rode with my parents, followed by my sisters and their families. My uncle, along with my cousin and her husband, completed the caravan. The idea was to float the Frio River and see Pat Green play at the House Pasture Cattle Company. Jerett would get to know my family and my home state intimately over the course of a few days. Unfortunately, on the day we arrived, a massive thunderstorm turned the clear water of the Frio a muddy brown. This cloaked the region’s natural beauty, and we had a less than picturesque weekend floating and swimming under cloudy skies, in even cloudier water. We made the best of it, but I wished he’d gotten to see the area in a different light.

I was half scared that once Jerett met my family, he’d run for the nonexistent hills. Compared to his reserved New England tribe, our posse of 10 probably seemed like one big, chaotic, multigenerational frat party. During the first 24 hours, my sisters skinny-dipped, my dad played “House of the Risin’ Sun” on his guitar, and my uncle nearly drowned in two feet of water while tubing. (Blame the beers.) Instead of fleeing in the night, though, Jerett asked my dad for my hand in marriage.

The vacation didn’t exactly endear him to Texas, but I figured that would come soon enough. If he loved my family, and he loved me, he’d surely come to appreciate the place that had shaped us—muddy water, gray skies, and all. In marriage as in life, though, things rarely turn out the way you think.

The loss of my mom eventually lured me—and us—away from California’s bougainvillea-filled streets. She had spent nearly four years undergoing treatment for cancer, and I flew back from Los Angeles to be with her every two or three months, sometimes alone, sometimes with Jerett, and eventually with our newborn son. During that time, my adopted home was slowly losing its hold on me. My concept of where I belonged was shifting once again.

When my mom passed away in the fall of 2018, I felt the need to be near my dad and sisters. I convinced myself Jerett would see Texas through my eyes, and he’d begin to understand the allure. I told myself, and him, he’d fit right in. After all, he loved barbecue, good beer, and cycling. How could he not adapt? He got a job in Round Rock, and we said goodbye to our friends in Los Angeles.

After a year in our new home, my husband still wasn’t settled—despite taking day trips to swim at Jacob’s Well and the Blue Hole in Wimberley, or driving to roadside barbecue joints and visiting every kid-friendly outdoor brewery we could find. The mesquite trees and live oaks failed to move him. The wildflowers didn’t last long enough to change his mind. The sound of the Union Pacific whistling in the distance didn’t remind him of his childhood like it did mine.

“This just isn’t where I imagined I’d end up,” he’d often say. Usually, the most positive review I would get from him was: “It’s a good place for kids, and the people are nice.” But something was missing, something I wasn’t sure I could fix.

It felt like the more I tried to force him to love his new home, the less he did. I was pulled in two directions. Moving home to help fill the space created by my mom’s absence seemed like the best decision I’d ever made. But at the same time, I was watching the person I loved struggle to feel the same way. After swimming and barbecue failed to do the trick, I decided a trip to my brother-in-law’s family ranch outside Llano would seduce my husband for good. He would look past the dust and the heat, or better yet look right at them, and find the beauty he longed for, right under his feet.

So, during a midsummer heat wave in 2020, we planned a trip with my dad and my sisters and their kids—after COVID tests and quarantining.

On the 90-minute drive from Round Rock to Honey Creek Ranch, I noticed the landscape get hillier and the chain restaurants give way to antique shops and mom and pop diners. Once in Llano, we took a paved road that gradually turned to crushed granite and gravel as the gas stations and supermarkets receded. It was just us, our wheels, and a flurry of dust.

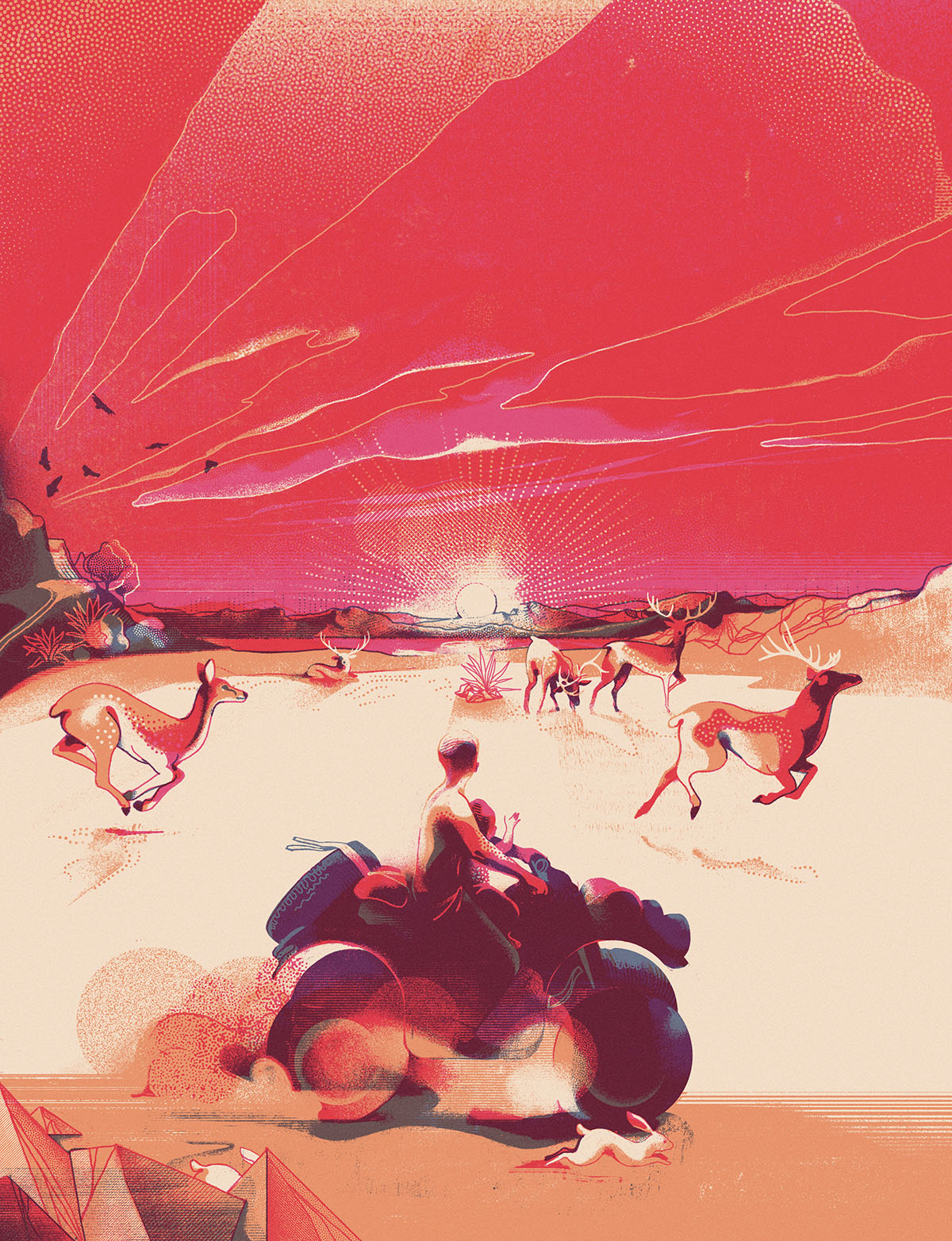

Llano is sometimes referred to as “the Deer Capital of Texas,” and as we drove, we spotted our fair share grazing or sprinting through the tall grass. There used to be occasional black bear sightings in the area 20 to 30 years ago, but now they’re extremely rare. There are still plenty of fanged and clawed things roaming among the cacti, though, and you can sense the bobcats, wild hogs, and snakes lurking in the brush.

The ranch encompasses over 1,000 acres in the Riley Mountains. Half of Dancer Peak is on the property, which offers unobstructed views of Packsaddle Mountain. Out in the distance, in a spot no one can seem to find, lies the mythical San Saba silver mine. Jim Bowie and several Spanish explorers attempted to locate this legendary place in the Hill Country, according to Texas lore. The ranch was the land of the Tonkawa, the Lipan Apache, and later the Comanche. Some believe the Jumanos traveled the land before that. Honey Creek is spring fed, and the water flows year-round, helping to keep the live oaks, cedar elm, Ashe juniper, and honey mesquite trees thriving.

Jerett’s newly acquired, midnight blue RAM 1500—his first pickup and the first sign he was maybe, possibly, acclimating to Texas—recorded the outdoor temperature as 109 degrees. I’d say that was a lowball estimate. Gone were the bluebonnets, Indian paintbrush, and pink-cupped evening primrose. But I’d been to the ranch in the spring, before I’d met my husband, and I’d seen the wildflowers in full bloom on a trip with my sisters and brothers-in-law. For three days, we had relaxed on the porch, grilled venison burgers from deer my brother-in-law had hunted, and slipped our feet into snake boots so we could walk along the creek. We drove four-wheelers up a steep cliff—past prickly pear, flowering Spanish dagger, and thickets of beebush—to watch the sunset each night. The ranch wasn’t mine, but I knew from my first visit that it was special. For years I’d dreamed of going back.

Jerett steered the truck from the gravel road into the ranch’s “camp,” which consisted of a main cabin, a hunter’s cabin, and a row of smaller sleeping cabins. A mud-caked Polaris and a rusty cream-colored 1988 Jeep Wrangler that had seen better days sat baking in the sun. Everything was baking in the sun, including my toddler son, whom I would follow around with a tube of sunscreen and a bottle of water all weekend. The heat was relentless, as were the sticker burrs, wasps, and biblically large grasshoppers that swarmed the area and accosted us every couple of steps we took. This is the kind of place where everything will sting, bite, or stick you, as they say. I loved it. I needed Jerett to love it, too.

As we toured the ranch, we gripped the sides of the Polaris to keep from flying out every time we lurched over boulders or 2-foot-tall cacti. A few miles in, dust-caked and sweaty, we stopped at a large pond so the older kids could fish for bass. When my brother-in-law pulled a dented metal rowboat toward the water, a boat the kids had been playing on a minute before, a large cottonmouth shifted in the dirt. Out came the shotgun, and my brother-in-law killed the snake as we watched. I looked at Jerett, who was holding his hands over our son’s ears to protect him from the noise. Jerett hated to see any living creature harmed—he would probably try and rescue a wild hyena if he could. I couldn’t gauge his reaction.

On many occasions, Jerett had told me about his childhood days spent riding an ATV through the woods behind his parents’ house, exploring the swamps, and building makeshift dams along the stream. As we rode around the ranch, he pointed out different plants and insects to our son, and showed him the rabbits, cows, and deer we spotted along the way. I knew this prickly terrain wasn’t as easy to love as a Southern California beach or a New England forest, and that it could take time to see the beauty in it. Still, Jerett’s curiosity about the landscape, and his obvious joy in explaining it to our son, gave me hope. As my brother-in-law drove, he talked about the history of the area. Jerett, always on the lookout for a wide-open space to call his own, casually mentioned he would love to own land like this. The ranch was working its magic.

After a long day of fishing and cruising the land, we settled in on the porch. Sunsets at Honey Creek are an event. From the main house, you can see miles of rolling hills and meandering valleys. The sky slowly shifts through hues of dusty coral and buttery yellow as everything settles into dusk. I wanted Jerett to feel as content in the moment as I did. Our love of a place comes in large part from the memories we make there—something unexpected that happened earlier in the day, an unforgettable meal, or an inside joke. A pretty sunset can do the trick, too.

“Isn’t this beautiful?” I asked.

“It’s nice,” said Jerett, looking out into the dark. What I think he meant was, “It’s not as nice as where we were before. It’s not a landscape I can get lost in. But it’s not half bad.”

Quietly, we watched the land grow still.

Early the next morning, Jerett went on a 50-mile bike ride. Leave it to a diehard cyclist to brave not just scorching temperatures, but the rocky, unpaved roads and cattle guards that weren’t meant for skinny bike tires. When he rolled back to camp, he was covered in dirt but looked content. He’d found some rolling hills and seen some wildlife, including a fox and plenty of deer. I asked him how the ride was and he answered, “It was nice.” This time, I believed him. He’d made a connection to the land, at last. How deeply that connection would be felt, and for how long, I couldn’t know.

Once he was back, I set off for a jog with my sister Kathryn. It was already 90 degrees at 10 a.m., so our pace was slow and steady. I was a little leery of critters and wildcats along the quiet road. Kathryn, who knew the ranch intimately, assured me there was no reason to be scared. While we ran, she asked me what Jerett thought of Round Rock.

“He’s getting used to it,” I said, not really believing my words.

Suddenly, Kathryn stopped dead in her tracks and picked up a large stick. “What was that?” she said.

Not five minutes earlier, she’d told me there was nothing to fear, and now she was gripping a makeshift weapon to fend off large beasts. I immediately conjured up scenes of the two of us being mauled by a pack of wild hogs. As much as I love the ranch, it’s still an unforgiving landscape. Like the state as a whole, you have to hang in there for the long haul, and embrace the good and the bad—the wildflowers and the sticker burrs—to really know it. You have to seek out the beauty amid the rough parts and accept them both.

“Should we turn back?” I asked.

“No, it’s fine,” she replied, as she took off sprinting down the road. I followed her, trying to keep pace, looking over my shoulder, curious about what she’d seen. Once we slowed down and my heart stopped racing, our fear gave way to laughter. My sister would never win an Oscar for attempting to appear calm in the face of imaginary predators. We agreed to keep running, gripping our sticks and staying watchful, just in case.

We eventually arrived back at camp and tossed our sticks aside. Jerett was driving the Polaris, with our son in his lap. I watched them for a while from a distance, laughing at who knows what as they circled around. I felt lucky to have them, whether it was here in this spot, or some other place. I hoped it would be here, though, and that the beauty of the ranch would help him see Texas in a different light.

Before our trip to Honey Creek, I sometimes questioned whether life would have been easier if I’d married someone from my home state. What would it be like not to feel the push and pull of trying to make the person you love also love your home, to eliminate any conflict about where you’re living, and why you’re living there? As popular as Texas has become, it’s not for everyone. It’s sometimes hard for me to admit that. It’s hellfire hot in summer, it’s rough around the edges, and there’s a headstrong wildness in the people and the land that I think not everyone can understand. But marriage isn’t about agreeing on everything, and you can’t predict what unexpected struggles will turn up. As I watched Jerett drive our son around that morning, making a memory all his own, I realized I couldn’t force him to love a place, or even to see it through my eyes. He had to get there on his own.

A few months later, Jerett and I sat watching a show about a famous chef who was living on a remote island in Patagonia. The chef said the island was his “deepest-rooted feeling for home.” The words struck me, and I glanced at Jerett, sitting next to me on the couch.

“It’s a land that you learn to love very slowly,” said the chef of his far-flung, windswept home, a place many would find too rugged, too tough. “Once you understand how she is,” he explained, “you start to love her.”

I hoped our weekend at Honey Creek might help Jerett understand this place a little better. I wondered if its coral sunsets and wild terrain lingered in his mind. Could he one day feel, like I did, that this place, and not California or Paris, was home? As we sat together on the couch, I still didn’t have the answers. Neither of us did. All I knew for sure was that here he was, right by my side. For the moment, it was all I needed to know.