An Open Palm

A state of grief becomes a state of solace for a new Texan

by Fowzia Karimi

If grief is a landscape, it is a vast misty hinterland, uninhabited but full of echoes, admitting a lone traveler. The traveler searches the wilderness for her lost one. And though it is a search in vain, through an immeasurable terrain, she cannot leave the land of grief where she searches for what is missing, as if it has simply been misplaced.

I am not unfamiliar with loss. I have never evaded the dead. But for as long as I can remember, I have lived in terror of one thing: the loss of my parents. I wonder sometimes if the early deaths I experienced of loved ones to war made me more tender. My parents, my sisters, and I immigrated to the U.S. in 1980 after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The atrocities during that violent and catastrophic time were innumerable. The war clung to us in California, where we regularly received news of loved ones who had been killed. Death was an early fact and facet of my life. And my heart was always a tender organ. As a 7- and 8-year-old, I would sit for hours at the window of our house in Los Angeles looking out onto the street and waiting with anguish—legs cramping beneath me, chin sore where it rested on the windowsill—for my parents to return home from a party. I knew it could happen in an instant. I knew it could happen when I was looking away. I yearned to have them back in the safekeeping of my vision. But decades later, when my mother died slowly in front of me over months, after battling cancer for almost two years, I found my eyes had no power to keep her in the world. I was 40, and I waited at the window for death, petrified.

I wish I could say when the moment arrived I faced it with strength or grace. My mother faced the cancer, the numerous surgeries, the chemo, and the radiation with incredible strength and profound grace. I spent those two years wearing terror like a vise around my heart. And then she was gone and the ground beneath me disappeared. If grief is a vast foggy wilderness, death is a solid steel wall, impenetrable to the gaze or the voice. Is it any wonder that the gaze turns inward after loss, that the dirge is not sung but swallowed whole to sit like an echo in the heart? This echo, this silent lament, gave muscle and rhythm to my broken heart after she died.

In the summer of 2014, on my mother’s 65th birthday, her doctor told her she had two months to live. I was in the middle of packing for a move from Oakland, California, to Denton, where my partner had accepted a job at the University of North Texas. My sisters and I immediately got into our cars and onto planes and flocked to her in Las Vegas. After her funeral, I spent five weeks looking after my father and tending to my mother’s things. Though it took another two years, at the time we anticipated my dad would move back to California. I packed and cleaned. I put aside the things my dad and sisters wanted to keep. I ran my mother’s brush through my hair. I drove carloads of donations to the thrift store. I scoured Vegas looking for a place that would take the wigs she’d worn through treatment. I cooked for my dad and served tea to his grieving visitors, but I smothered my own emotions. I forced myself to eat and exhausted my body each day so that when I put my head down at night my mother’s absence would not choke me.

A move is usually a momentous occasion, a time of excitement, trepidation, tumult, and wonder. I landed in DFW a sleepwalker. I don’t remember the drive to Denton. I know it was October, but I remember very little of those first several months in Texas. I was home with my partner and our dog, but I had little awareness of where I lived, the people around me and with whom I interacted, the places I drove to or through. I wasn’t incapable, nor did I lack momentum; I pushed hard to do, to produce, to exhaust myself. But while my body occupied one space, my heart and mind lived in the vast expanse of grief. My mother’s scent was still in my nostrils. My heart, so long in terror’s relentless grip, was ripe and ready to burst. Tears held in for weeks ran hotly and unceasingly at all hours, in all places, during that first year—onto my dog’s head and back, in grocery store parking lots, in restaurant bathroom stalls, at stoplights, while I slept and dreamt, showered, ate, wrote and read, dug into the garden soil, sat in front of the television, leafed through volumes at the bookstore. It’s how I came to know Texas, through a sheet of tears. I’m very familiar with loss. I’ve never dismissed the dead. But this was my mother.

My mother, who generated love like the sun generates light and heat, was home, was country, was the bright star in the center of our solar system. Her absence dimmed the sky and chilled the air.

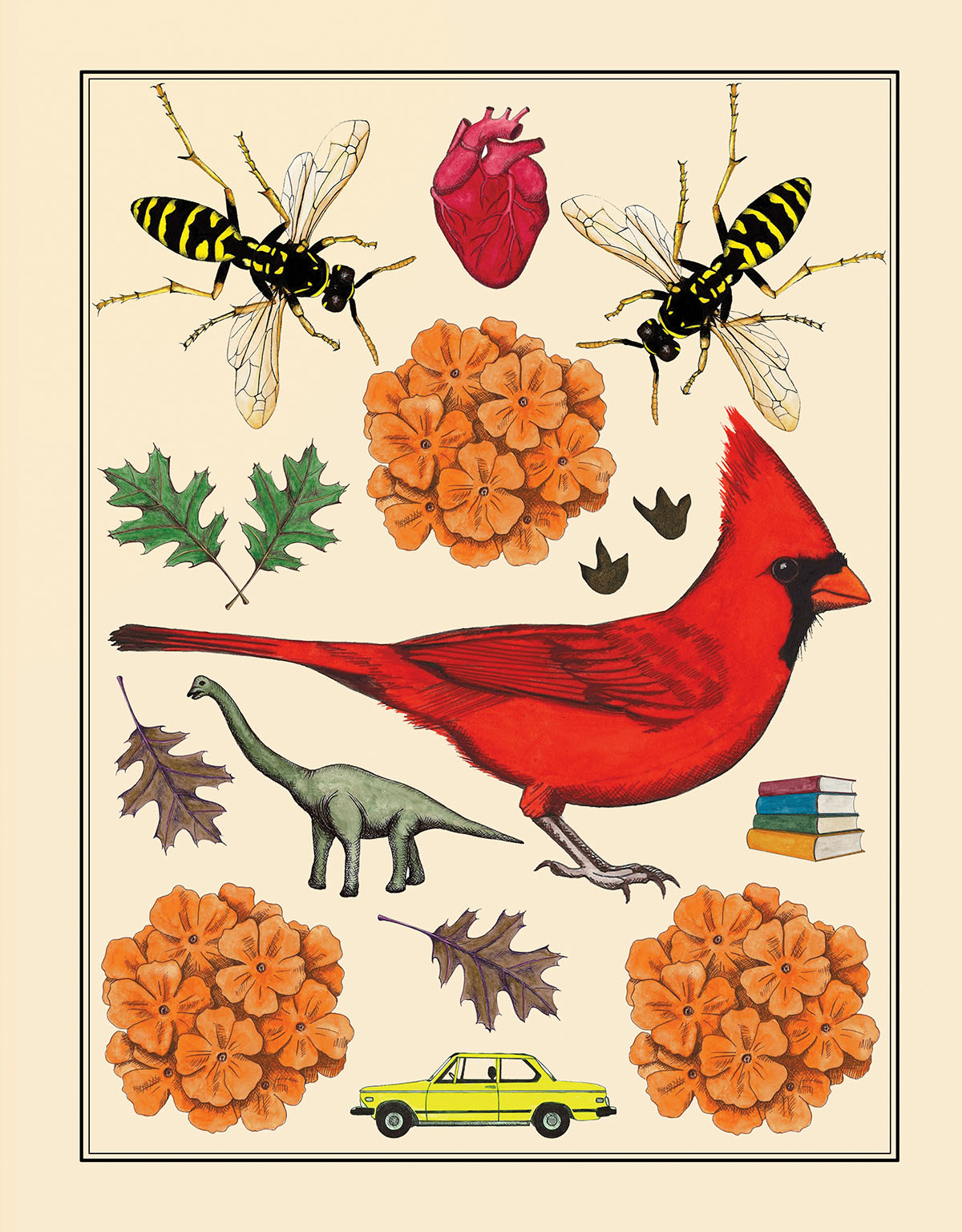

The space of grief is infinite but allows only a shallow depth of field. During this raw and tender period, I’d return from the hinterland for brief moments—not by conscious choice but as if tugged on. Suddenly, the cashier across from me would come into focus, her smile warm, her chatter bright. The red cardinal streaking against the green leaves of the oaks would awaken me to the leaves themselves, their rhythmic patterns coming into relief against a blue sky. Beads of ice adorning naked branches, the warm buzzing of wasps at the portals of their dwelling, a stranger’s hand lingering on a doorknob as he held the door open for me, a neighbor’s good morning, light and sincere—these things tugged on me and focused my attention. In momentarily returning to the world, in finding myself in a new city, a new state, I was not shocked but comforted.

My partner had arrived in Texas three months before I did. There were places he wanted to take me, meals and stories he wanted to share. He was keen to draw me out, to comfort me. I don’t remember how long I’d been in Texas when we made the trip to Glen Rose. It may have been two months; it may have been 10. Road trips have a way of realigning me with my romantic nature. Routine life and its restraints fall away, and I am fully awake to the changing landscape outside the car windows; the play of light on a building roof or across an unshorn farm field; the wildflowers native, planted, or renegade; the song or interview on the radio; the hills or the city on the horizon; the cold sandwich in my hand; the road stop at the bustling gas station or in the shade of the only clump of trees for 200 miles; the city congested at rush hour and flushed with the hue of the setting sun; the sea’s dew on my skin. The road awakens me, reorients me with my true nature. This trip to Glen Rose took place not in a state of wakefulness but in a trance, a sea of mourning. For years, I recalled it as a dream. When I realized we had in fact made such a trip, I had to look up “the place with the dinosaur tracks” to figure out where we’d gone.

Central Texas was covered by a large shallow sea 113 million years ago. The area that is now Glen Rose sat at the edge of this ancient body of water. Dinosaurs, walking across the limey mud of its tidal flats, left their tracks as evidence of their size, weight, and feeding and social habits. Their prints, and their story, were fossilized and hidden beneath layers of sediment until the early 20th century, when a flood on the Paluxy River exposed them to human eyes, the only eyes that would heed their novelty. Two very distinct print types—one made by a plant-eating sauropod, the other by a carnivorous theropod—crisscross the riverbed. The sauropods moved in groups and protected their young by placing them in the center of their roving clusters. The sprightly, predatory theropods hunted the larger species. It’s hard to wrap one’s head around such an expanse of time. And yet, there they are, 113-million-year-old footprints reading like text in the limestone bed of the river. A primitive alphabet, a zoological scripture, a letter written, in two distinct fonts, by two species long extinct to one only recently arrived.

I remember seeing the footprints on that trip years ago to Dinosaur Valley State Park but hardly remember how I got to where they were. Still, the road trip to Glen Rose imprinted itself on me even through the haze of grief because it did what my partner had hoped it would do: It comforted me. Texas—its big expanse of sky; the land like an open palm; the close, bright sun; the warmth and kindness of strangers—comforted me. In my memory of that trip, I glimpse loops and lengths of highway along which only the nearest and random objects came into focus and went out of view again as grief pulled me back into its depths, onto its own limitless highways and expanses. The town squares we drove through from Denton to Glen Rose were like islands in that sea of mourning. They were like nothing I’d experienced before in the U.S.: their colossal stone courthouses and fluttering state flags, the upright brick buildings from earlier eras housing busy eateries and bars, shop windows decorated with bright colors and local pride, nostalgia and modernity, bustle and cheer, culture and history, all concentrated across a few blocks. I was in a new land. Texas revealed and declared itself, even as vivid pictures of my mother’s face at different ages of my childhood played across my lids when I closed my eyes, even as the echo of her laugh thrilled my eardrum and drowned out the song on the radio.

I have a very long and keen memory, so it is strange for me to look back on a trip and see it through a fog, its outlines blurred. So much of my external life during that year—the life of the senses; the life of experience; the life of society, place, and time—was not recorded. What was being experienced internally was so much sharper. Images of Glen Rose flash like snapshots in my memory now. Strings of lights, lit in the bright middle of day, wrapped around leaning poles. The small stature of old buildings. A bookshop with its stacks of old books and their beautifully set type—and the type’s impression on the soft page—reminding me of my own mortality and placement in time. There was the waitress at the café who hesitated only momentarily before she realized the tea I asked for must be of the hot kind, not sweetened and with ice. I can’t remember her exact words, but I’m certain they ended with “Not a problem, honey.” Everywhere we went, there was the thank you; the please; the after you, ma’am; the come on in; and the y’all have a good day—phrases as common in Texan parlance as the native red, black, and live oaks in its landscape. And there was color! It may have been the abundance and celebration of color in Glen Rose that most urgently tugged on me and drew me out for moments. The decor of the small town—its sidewalks and shop windows adorned with turquoise and lavender metal roosters, pink and gold silk flowers, shiny blue pinwheels—stood in vivid contrast to the browns and greens of the surrounding landscape. And stood in even greater contrast against the dinosaur tracks and the millions of years that separate our infant species from their long-lived ones.

The span of time between the era of the dinosaurs and our current one is incomprehensible. Homo sapiens have been here for 300,000 years, our ancestors for 6 million. The dinosaurs that went extinct 65 million years ago roamed this planet for 165 million years, while the continents beneath them slowly drifted apart. Our relationship with time is one of the most intimate we have, inseparable from our experience of life, like breath, like water. We live dissolved in a solution of time. Time envelopes us, permeates our very human existence. Yet it is a slippery thing we can’t grasp. The dinosaurs were. My mother was. I am. Yes, our measurement of time is bound to our experience on this planet, but whether measured in lunar or solar cycles, our clocks and calendars can’t hold time. The shapeless, malleable thing expands and shrinks, speeds up and slows down, runs fluidly or dries up, much like the Paluxy River over the course of the year, which alternately exposes and covers its tracks.

Grief is full of infinite space, but it is timeless. Time continues to beat in the outer world, but within the mourner its meter is dulled. Because grief circumscribes all knowing and being, time relents, retreats. When during that first year did we make the trip to Glen Rose? In that span, we had moved twice, first to Texas, then from an apartment to our first house, both in Denton. I made the two moves, I planted a garden, I painted pictures and worked on my book, but I did it all outside of time. With her voice still warm in my ear, my hand continuously reaching for my phone to call her, how could I measure the time between any present moment and the last conversation I had with my mother? I could still hear her say my name, shortened and pronounced as only she did; hear her laughter as she related the most recent news in her community; hear the concern in her voice as she asked after our dog’s health.

That year, I met my new home of Texas again and again, bumping into it softly, waking to it gently. I was raw and bruised, and each gentle tug let me know I was surrounded by kindness. It has been nearly eight years since my mother’s passing and my move to Denton. She knew we were moving here, but she didn’t live to see it happen. So, my eight years here have been motherless. But they have not lacked solace and warmth. There is something in the spirit of the state, a beautiful blend of courtesy, optimism, generosity, and pride—mirrored in its big sky and limitless landscape—that gave me the space I needed to fully grieve. Repeatedly, I was surprised by the genuine, easy kindness of Texans, from the antiques shop owner who let us bring home a pair of side tables to try out without asking for any collateral or ID; to the young jeweler and mother who invited me to her farm studio to make a pair of leather earrings and meet her family and their animals; to the neighbor one street over who returned a piece of misdelivered mail, and who has since become one of my dearest friends. And one day I found myself able to return the warmth and lightness, happy to be among such people.

I am familiar with death. In making its rounds, it has often passed by my door. In late January of 2021, a year into the pandemic, in the midst of global grief, I found a tumor in my left breast. The old visitor had returned, this time entering to sit at my side, where I felt its breath on my cheek. I received the cancer diagnosis over the phone two days before the arrival of the big freeze that shut down the entire state. Time itself seemingly froze as appointments were canceled, test results lost, next steps, new doctors, uncertain. My partner and I spent our anniversary writing our wills and my advance directives while shivering under multiple blankets as we waited in frigid temperatures for the electricity to come back on. I closed my eyes and saw it, the dark-hooded entity, straight out of a film, or a cartoon, yet present and palpable. During this past year it appeared regularly and glided down our hallways, passed through my dreams, kept vigil in the shadowy corner of my bedroom.

I have just come out of the other side of a long and excruciating year of treatment, cancer-free but still suffering from the treatment’s brutal assault on my body. Grateful is not a word that comes to mind often during cancer treatment, but I regularly felt grateful my journey took place here, in Texas. That at every turn I was surrounded by, and my pain cushioned by, tenderness and warmth, optimism and generosity. In midlife, life and death have met within me, my own body now a memento mori. What is time now? What have I left of it? I have moments that bloom like clusters of flowers, bright and vivid against a world that has shifted, globally and in my own life. Moments when I awake, as if from a terrible dream, to realize I made it through this past year. I made it through with strength and with grace. Moments with my partner and our dogs that linger, sweet and brimful. The dinosaurs were. I am. For a brief moment, I am.