Hold on for Your Life

A mutton busting competition binds a mother and son to their Texas roots

Anyone could apply for one of the spots, but I had no idea how the rodeo officials chose the participants. Luck of the draw? First come, first served? All I knew is I paid an application fee, filled out a form with my son’s name, age, and weight, and sent it off into the ether.

“Townes got in!” I squealed. “It’s really happening! I can’t believe it!”

My ex-husband and I named our son Townes after the singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt because we had fallen in love to his album Live at the Old Quarter. Van Zandt hailed from Fort Worth, where we were living at the time, and he sang odes to bandits, ne’er-do-wells, and country girls. Townes seemed like a perfect Texas name, promising a childhood spent running wild in the great outdoors. However, my Townes’ childhood in the city had precluded such activities as building forts in the shrubby woods or riding horses or hunting for crawdads next to a warm creek. The rodeo was my son’s chance to connect with his roots.

“You act like he just got accepted into Harvard,” my mother replied. “Now what is it he’s doing again?”

“Mutton busting!” I repeated, for at least the 10th time. “He’s mutton busting at the Fort Worth Rodeo! We’ll need to get everyone tickets to watch him.”

“Sure, but what is mutton busting?” my mother asked.

Although they are fifth-generation Texans, my parents frequent the Fort Worth Opera far more than they do the Fort Worth Stockyards. It’s entirely possible that neither of them has ever ridden a horse nor kicked up dust two-stepping in a country bar. Avid world travelers who had lived in Puerto Rico and Peru, my folks always struck me as disinterested in the trappings of Texas lore. I’ve never seen either of them do anything particularly “Texan” unless forced.

For example: In the late ’80s, my father’s company, a global pharmaceutical manufacturer that chose Fort Worth as its home base, hosted some overseas clients. The weekend included a visit to Billy Bob’s Texas to show the foreign visitors some local color. My mother, then 48, had to buy cowboy boots at some tourist shop in the Stockyards to support the illusion of being a rollicking Texas gal.

All of this transpired despite actual Texas bona fides from both sides of the family, a larger-than-life history I adore. My grandma used to tell me how her great-grandmother could drive a team of 10 horses by herself and how her father, country-western songwriter J.R. Cheatham, penned two tunes featured on a 1963 album entitled Diesel Smoke, Dangerous Curves and Other Truck Driving Favorites: “Blue Endless Highway” and “Sleeper Cab Blues.” I wondered if a deep and abiding love of Texas had somehow skipped my parents’ generation and was threatening to skip mine and my son’s.

I spent the better part of 10 years away from Texas in New York and California. In that decade I lost my accent and accumulated a wardrobe of primarily black and gray hues. I cut my hair, adopting prominent bangs that somehow seemed more Manhattan than Dallas. I love those big, coastal cities and relished the feeling of anonymity and opportunity they afforded me, but nothing compares to the Lone Star State and its mythos. I was beguiled by the “everything is bigger in Texas” attitude and by its reticence to let go of a cowboy culture that has long since faded from day-to-day reality for most of its residents. The closest I’ve gotten to livestock lately is a road trip to Fossil Rim in Glen Rose to feed nonnative quadrupeds from the safety of my RAV4.

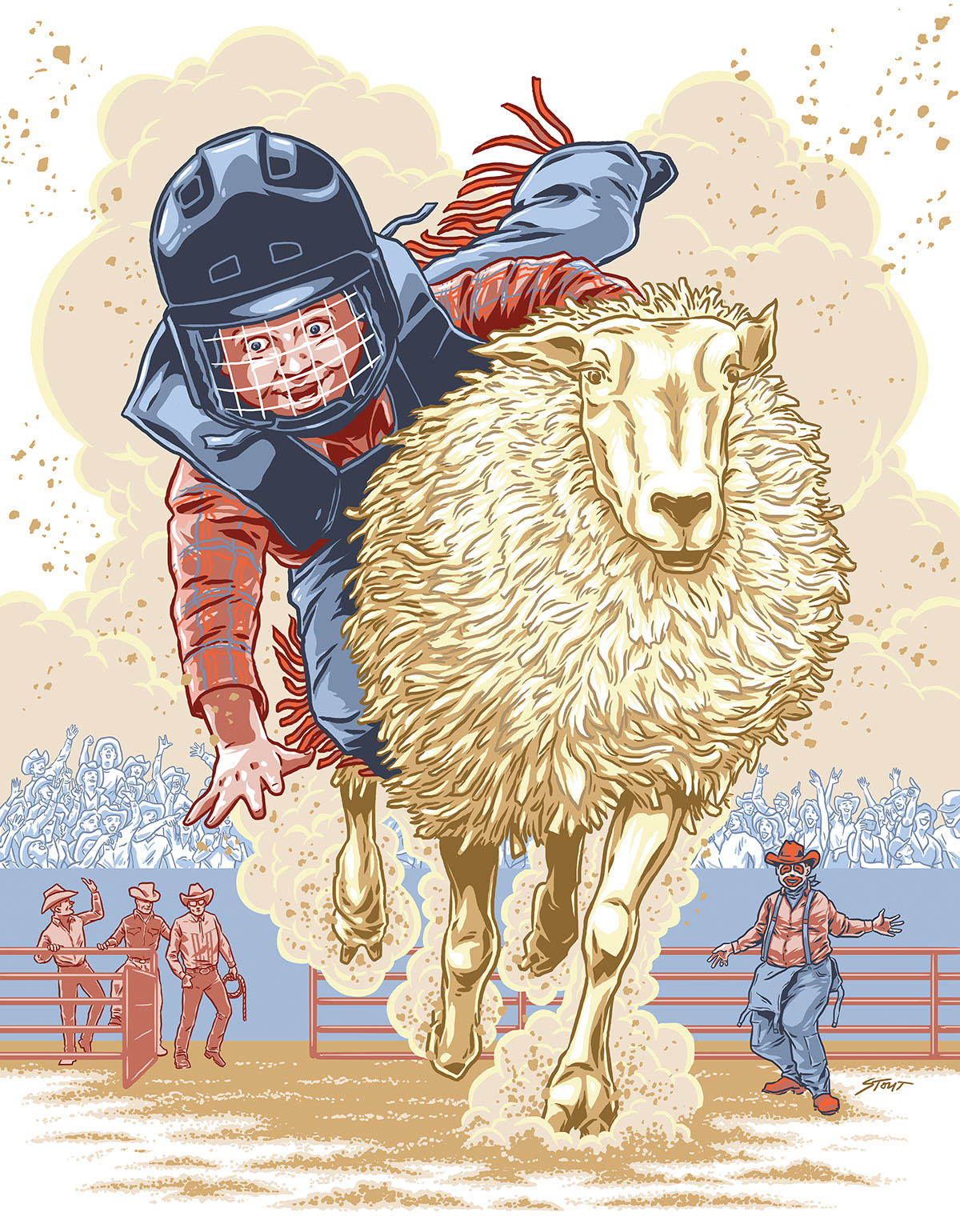

I explained to my mother yet again the event for which I had signed up her grandson. Mutton busting is a fan favorite in rodeos across Texas. The competition involves dressing children between the ages of 4 and 7 (who weigh under 55 pounds) in bull riding gear—helmet, chaps, vest, the whole get-up—and then setting them on a sheep so furry it looks like a kitchen mop. The mutton burst out of mini bull chutes, with the kids nearly laying on top of them and clutching their wool in lieu of reins. As often as not, the kids slide comically off, caught by the forgiving sands of the arena, met with the gleeful applause of a rapt audience.

“Well, I’m not sure I get it,” my mother said, “but your father and I will be there to cheer Townes on.”

I grew up in a town on the outskirts of DFW with three stoplights, amateur rodeo, and 13 Baptist churches. I don’t know if the church part is totally accurate, but it certainly captures the sense of Mansfield in the 1980s, when the only two non-chain restaurants were the Bronco Café, open for breakfast and lunch; and the Rodeo City Café, providing hearty chicken-fried steaks for dinner. My parents had chosen the area for its stellar public schools and its Mayberry-esque sense of community, plus it was close enough to an airport to temporarily escape small-town life if it got too small.

The main entertainment in town was the Kow Bell Indoor Rodeo. Right off US 287, it proudly announced itself with a bright yellow sign and red lettering crafted to look like rope from a lasso. Bill Hogg opened the Kow Bell in 1959, and for nearly 50 years it held year-round rodeos on Saturday nights, presumably leaving Fridays free for high school football. The building was constructed from a large prefab barn and surrounded by what looked like wooden backyard fencing. Above a porch held up by columns fashioned from tree branches, a mural featuring lopsided, rough-hewn drawings of a barrel racer, bull rider, and calf roper greeted rodeogoers with a hint of the action inside. My parents never once took me, but I wondered about it every time we passed by.

An unlikely source finally introduced me to the rodeo. A colleague of my father’s had moved his family, including their two sons, from Belgium to Mansfield. The oldest, Wim, was my age. To be from Belgium seemed almost magical—all superior chocolates and french fries with mayonnaise (a stroke of culinary genius in my opinion, raised as I was on sandwiches my grandfather “Poppy” made, consisting only of white bread and mayo). Wim’s parents employed an au pair. I had never heard of such a thing. When my parents went out, a high school student who lived across the street babysat me. Wim’s “babysitter” lived with their family all year. I can only imagine now how bizarre it must have been for her—to go from bustling Brussels to a place with no movie theater and only a few piddly blocks of downtown. Perhaps that’s why she suggested taking me and Wim to the rodeo.

I can still remember the sweet, earthy smell of the sand and the animals, the feeling of my 7-year-old boot-clad feet swinging from the stadium chair because I was too short to touch the ground. At some point, they called for us kids to come down and chase a single calf let loose in the arena. The first child to snag the blue ribbon from the calf’s neck would win a whole dollar and have their name heralded from the loudspeaker. Little boys in jeans and sweatshirts popped up like whack-a-moles, racing down in search of victory. The girls stayed seated.

“You two should go down there!” the au pair said to Wim and me. I hesitated. Spectacularly unathletic even then, I dreaded humiliation. “I’ll be the only girl,” I said. “Even better,” she replied in her rounded accent, giving my shoulders a push in the direction of the aisle.

Memory falters here, but I do remember the chaos of kids’ bodies crashing into one another in a desperate attempt to capture a calf careering through us like its tail was on fire. A rodeo clown appeared, his face leathery beneath a grease-painted smile. He held the squirming calf by the tail, and I saw my chance. I elbowed little boys out of my way, struck with the passion of Joan of Arc launching into battle. My nimble fingers felt the plastic edge of the ribbon around the cow’s neck. I grabbed it and yanked, immediately bewildered but jubilant at my win. Someone asked for my name, and the next second I heard the announcers broadcast it over the PA system. “I’m famous,” I thought just as I saw the dollar bill flutter down from the announcers’ box above the chutes, as if from the rodeo gods themselves.

Once home, I proudly presented my mother with the blue ribbon that had adorned the calf’s neck. She reacted as she might have to a cat gifting her a bloody mouse. “What do you want me to do with it?” she asked, genuinely curious. It was Christmas, and inspired by holiday spirit and buoyed by triumph, I said, “We should hang it on the tree!” To her credit, she did. She placed it in a glass bauble. On it she wrote “Andrea, Winner-Calf Chase, Kow Bell Rodeo, Mansfield, c. 1985.” For 35 years, it has steadfastly hung from the scratchy branches of our Christmas spruce, and I’ve been hooked on the rodeo ever since.

We moved from Mansfield to Arlington about the time I started high school. Gone was the Kow Bell and its rustic charm. Instead, each January, my friends and I flocked to the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo, incongruently nestled between the city’s botanical gardens and nationally renowned museums. We would pop on our cowboy boots and explore the midway set in front of Will Rogers Coliseum, testing the fortitude of our stomachs by gorging ourselves on nachos, then hopping onto rides that spun you sideways and upside down. If we were lucky, someone’s mom or dad worked for the Basses or Moncriefs or Carters—those formidable scions of Fort Worth—and called in a favor to score us the coveted box seats where nothing stood between us and the arena but some flimsy wood.

Leaning out over the railings, we’d high-five the cowboys parading in, flinch when the barrel racers kicked dirt into our Diet Cokes, and stand up on tiptoes to see the pens where taut-muscled men tried to balance on soon-to-be-bucking broncos. Once, my friend Melissa and I witnessed a bull, flush with rage, clatter its horns against the walls of our box, the man riding him flung around like a rag doll. We couldn’t help but squeal with delight.

The rodeo came to signify far more than an evening’s entertainment. I relished times spent wandering aimlessly through the cattle barn with a boyfriend, gossiping with my girlfriends atop the midway Ferris wheel with the city as a glittering backdrop, or dropping a ridiculous $20 to buy a commemorative program hawked by a blond Junior League volunteer. I felt present at the rodeo, mindful among the whir of action. I was there and only there, not worried about whatever new problem my anxious teenage brain rallied around. I felt distinctly Texan in a way I rarely did.

When I sent in my son’s application for mutton busting, I was signing him up for a type of Texas heritage that my grandmother had boasted about—tall tales of grit and humor with a bit of the absurd added in for flair. Our family came from Germany and Ireland before settling for a bit in Tennessee, then heading southwest to search for fortune in Texas. We farmed cotton and weathered the Depression by running a café next to a dance hall. My great-uncle was friends with LBJ and once advised the ladies of the Chicken Ranch about tax deductions. My grandfather worked at Texas Instruments in its early years but walked off the job after seeing rabbit tracks in the snow from his building’s window, which inspired him to go hunting. My parents grew up with relatively little, telling stories about taking care of their youngest siblings or riding on Dallas trollies alone to see “the picture show” downtown. Perhaps their disinterest in things like the rodeo stemmed from seeing enough of hardscrabble Texas life.

I wanted my son to have a sense of belonging to Texas’ singular history, perhaps even a little bit of a Western fantasy that whispered the possibility for adventure and freedom in a way our current lives in Dallas do not. He didn’t grow up like me, running through neighbors’ fields, picking wildflowers, and feeding apples to horses at a friend’s ranch. Born in Fort Worth and raised in Dallas, his games are more regulated—Little League Baseball or Topgolf or the all-consuming Minecraft with friends on his Nintendo Switch. I wanted him to have a bit of the old-fashioned magic only the rodeo could provide.

The big day arrived on Jan. 12, 2018. By then, I had informed pretty much every person I knew that Townes would be mutton busting—friends, family, colleagues, the bank teller, our server at Torchy’s Tacos. It was bitterly cold, but that didn’t stop Townes’ “girlfriend” from kindergarten, his babysitter and her family, my parents, and his dad from braving the arctic winds to attend. Still, despite his numerous fans, Townes seemed a bit uncertain.

We explained what he’d be doing and had even discussed strategy with him: “Grab its fur and hang on really, really tight! Try to maintain your center of balance!” Townes shrugged us off. What did we know about riding sheep? Still, we rained praise and encouragement, trying to pep him up for his grand performance. We also promised him a windfall of junk food and carnival games post-rodeo.

His dad and I gathered in front of Will Rogers Coliseum, its magnificent art-deco tower standing sentinel over Fort Worth, before heading into the arena. We checked in with the mutton busting folks so Townes could pick up his ensemble—long-sleeved event T-shirt, red chaps, black vest, and helmet. Decked out like a mini-Tuff Hedeman, Townes led us to our seats up in the nosebleed section, where we would watch the first half of the show before escorting the kiddo down into the action.

I noticed for the first time how old and rough around the edges the building was. (Two years later, the rodeo would move to the new Dickies Arena.) But I didn’t care. I was high on excitement, buying a doodad that spun and lit up for Townes to wave around. I took a thousand pictures. Eventually, my usually patient son grew annoyed. “Momma, stop!”

I remember the exact feeling of walking hand in hand with my son onto the arena floor. It was the first time I’d seen the coliseum from that view, and the packed house seemed oddly intimate, small even, like many childhood places do when you return as an adult. My boots sank several inches into the red dirt with every step as we made our way to two tiny rodeo chutes. We got in line behind the other parents, equally gleeful but a bit nervous, like we were waiting on a promising blind date to arrive. We watched as a dad in a button-up shirt lifted his daughter into the chute, setting her down on the sheep as a rodeo official looked on. Then bam! The chute door opened and the sheep took off like a shot in the dark, all spindly legs and shaggy fur, the little girl holding on for dear life.

Townes, his dad, and I watched, stock-still, as the sheep raced the length of the arena before the girl fell off. A rodeo clown ran to get her, lifting her high above his shoulders as the crowd whooped and hollered its approval. Townes turned to me. “Mom,” he said, hesitating, clearly nervous. “You got this, buddy,” I replied, and gave him a gentle push from behind, a ridiculous parenting moment my ex-husband captured in a photo.

I stood back so I could film the entire event on my phone. Townes’ father lifted him up into the chute, and I lost sight of him. The next part happened so fast that I am forever grateful for the video. The chute opened, and nothing happened. At first. Then, the sheep burst forth, my little boy wrapped around him, trying hard to stay on. After what couldn’t even have been a full second, he slid right off, landing in the soft earth. I watched him lift his head, saw the red sand pour out of his helmet before his dad rushed to grab him.

Townes was a bit stunned, but when it came time to pose for photos with the bull riders, he whispered, “I am a real cowboy,” as if he couldn’t believe it. He left positively beaming, holding his trophy and the special Western-style belt buckle awarded to all riders. We met his kindergarten friend outside, and in lieu of embarrassment, he yelled, “Did you see me fall off? It was awesome!” And off we went for funnel cakes.

Townes has never worn his special mutton busting belt buckle, but his trophy sits proudly on a shelf in his room. That piece of hardware has made an appearance at four years’ worth of school show and tells, and it looks a little worse for wear. A photo hangs in our hallway of my son indelicately sliding off a moving sheep. “That’s me!” he’ll tell friends who come over for play dates. We still watch the video with regularity, my mother laughing until she cries. Sometimes, when I’m putting Townes to bed after we read a chapter of Harry Potter and he cycles through his endless litany of existential questions—Would you rather be a werewolf or vampire? Where was I before I was born? Do you think lobsters dream?—he’ll spot the photo on the wall outside his room and ask me if I remember him mutton busting.

“I do,” I say. “Do you?”

“Totally,” he replies. “It was magic.”